The Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, UK, has never held a major exhibition features contemporary art until it decided to break the tradition with “Landscape Landscript”, a solo show by the contemporary Chinese artist Xu Bing opened on February 27. Xu has been a creative artist for more than 30 years, and his name appeared in art history textbooks as early as the 1990s. His work is part of the collections of numerous international museums and galleries, including the British Museum and the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York.

Being one of today’s most internationally renowned contemporary Chinese artists, Xu Bing has been fascinated by language. “Book from the Sky”(1988) made his name in China and the West, consisted of an installation of books and scrolls hand-printed with his unique Chinese characters. His “Book from the Ground”(2012) , a novel written in a language of icons, featured classical Chinese calligraphy, printed text and pictograms. His latest series of “Landscape Landscript” on view at the Ashmolean Museum is based on the 17th Century Chinese landscape paintings that he repaint them using Chinese characters. Reflecting on his personal engagement with language, his writes that, “I am through and through a Chinese person, of the species Chinese artist.”

Ashmolean Museum, March 2013

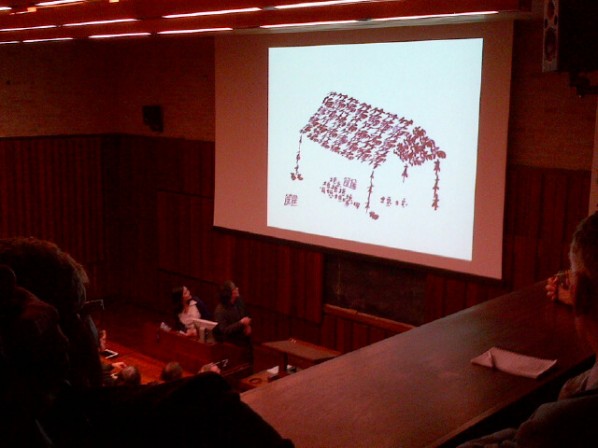

Xu Bing was in conversation with the Director of the Ashmolean, the Director of the Courtauld Institute and the former Director of the Victoria & Albert Museum at the opening.

As one of top museums embrace studies on Chinese Art, Ashmolean Museum has collected Chinese art works from Neolithic age through the modern period, how do you find it, that the museum starts its exhibition programme of 2013 with your work?

Many important large museums and many major secular museums are similar in the way they exhibit ancient Chinese art but they now also look towards contemporary art to attract a bigger audience and more revenue, but without any organic connections. Last year was the 25th anniversary of the secular museum and this is the first contemporary art show so it seems appropriate to be in the Ashmolean as the founding secular museum but it is the first to hold a contemporary Chinese art show of this kind with links to ancient works. I am honoured to be selected as the artist for the Museum’s first major exhibition of contemporary art. The Ashmolean has a special connection with Asian museums and contemporary art has become a common trend. The Ashmolean told me that it was the last major museum to introduce contemporary art so it is the first in one respect and last in the other. It is seamless and there is no rupture between the traditional and contemporary here.

You have talked about the discussion on tradition and contemporary, could this exhibition cooperated with the museum be taken as a further exploration on it?

There has been good cooperation and it is a beautiful space with a good atmosphere that suits the exhibition, you feel happy in this space. The landscape surrounding Oxford is very good and it’s appropriate for my work in Landscript. I like the Ashmolean because there are a lot of stories to the collections in the stacks and not just randomly selected. There is a genuine respect for the audience and not imposed by the curators, a happy balance.

As far as I know, you have picked masterpieces from France created in the 19th century to exhibit along with your work, meanwhile, the Russian art education you have been cultivated in is closely related with French tradition. What kind of dialogue do you want to build between these masterpieces and your “New Landscape” or “New Landscript” ?

I am fascinated by 19th century French art as it is more sensitive to the Chinese way of painting and my fascination is with Chinese art. My liking of French art must have something to do with my long training in Western art along with developing interest in Chinese art following my visit to the USA. This is a dialogue in Landscript about a writing system that articulates something different from the Western system and I found that the Chinese system is very different from the Western system.

Would you briefly talk about the relationship between Chinese tradition and Contemporary Chinese art, as well as the relationship between eastern and western art in this exhibition?

Chinese art is actually positioned in this intersection due to the tremendous impact of Western art over the last century when everyone paid attention to it but the Chinese tradition is in the blood so it is between two cultures and that causes a dilemma and there is no experience of how to use our own culture to express ourselves. How to reuse ancient wisdom and knowledge which we lack experience in? The relationship between traditional and modern, Eastern and Western is not clear cut but intermingled, if we look at the Song paintings they are great but it is unclear why, because modern elements in Song paintings resonate. Western masters become masters because they find something outside their culture. This is how I think, no matter old or new, west or east, good art brings you to a new horizon.

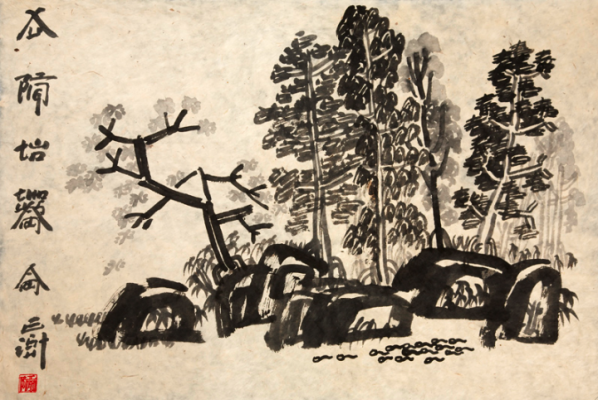

A 2008 ink-painting in the Landscript series. Each natural element in the painting is represented by its corresponding Chinese pictograph.

Prof. Peter McDonald of St Hugh’s College, Oxford, expressed the view that Xu Bing’s art is deeply rooted in a Buddhist tradition: each piece is a koan — a statement that teasingly defies logic. The exhibition’s curator, Shelagh Vainker, agrees his commentary and she thinks that Xu Bing has succeeded in developing his wit into the lingua franca that transcends all barriers of culture and language.

Xu Bing was born in Chongqing in 1955 and grew up in Beijing. In 1990, he left China for America. A long-term resident of New York and a critically acclaimed name in the global art market, Xu in 1999 received a MacArthur Foundation Genius Award, one of the most prestigious cultural prizes in the United States, for “his originality, creativity, and capacity to contribute importantly to society.” Furthermore, in recognition of his contributions to Asian culture, he was awarded the 2003 Fukuoka Asian Culture Prize, and in 2004 was given the first Wales International Visual Art Prize, Artes Mundi. In 2004, Xu Bing, together with 15 other international artists, was featured in Art in America magazine’s “People in Review” column, signifying his status as an innovative and influential trailblazer. In 2008 he returned to Beijing to work as vice-president of the Central Academy of Fine Arts. Thereafter he has become the backbone of CAFA who actively advocates advanced art education and communications.

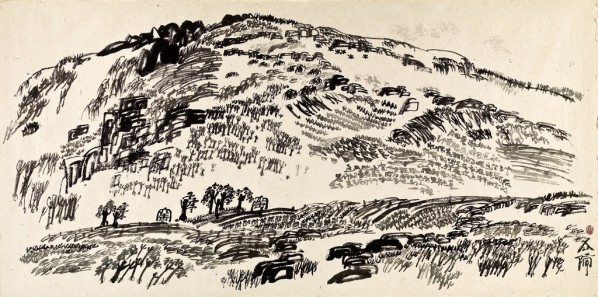

Xu Bing, Landscript, 2004; Ink on Nepalese paper, 150x300cm

As its name indicates, “Landscript” shows a landscape made up out of Chinese characters, a typical setup for Xu Bing. At first glance, one has the impression of a free-hand brushwork painting in the classical Chinese style, but a closer observation reveals that instead of conventional brush-strokes, the elements of the scenery are in fact composed of pictographic Chinese characters carrying connotations such as “mountain,” “cloud,” “rock,” “grass,” or “leaf.” Moreover, there is an assortment of faux characters invented by the artist. Together, the “real” and “bogus” scripts merge into a natural vista with a considerable undertow of irony and even mockery: on the surface, the painting might be seen as an epitome of the ancient Chinese aesthetic axiom that painting and calligraphy are just two sides of the same coin. Yet Xu’s approach pushes this idea to the point where the concrete and the abstract begin to overlap in a confusing way. In revealing how writing can be used to convey meaning, but also create distance, he exposes the fragile nature of perception and communication. The pictographic or ideographic nature of some of the more basic Chinese characters may allow their meaning to be guessed even by the uninitiated, but most characters are the result of a long and complex evolution, and by no means easily understood. As Xu puts it, “My work invariably possesses a clue implying an attitude—skeptical of prevailing beliefs. Why do we use characters? Characters are the most basic element of human cultures. To reform characters is to reform the most basic substance of human thinking.” “Landscript” is a concrete manifestation of this approach, both a sweeping survey and culmination of the long-standing Chinese tradition of blending poetry, calligraphy and painting into one.

Related report:

1. Landscapes full of character by The Telegraph

Courtesy of the artist and the Ashmolean Museum, for further information please visit www.ashmolean.org.