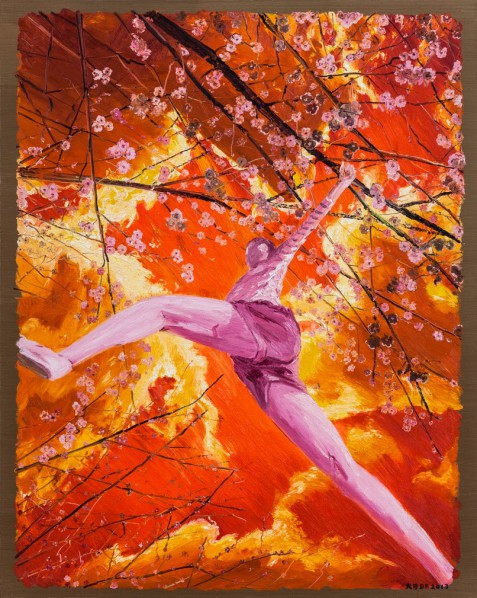

Chen Ke, Plum - Spring Song No. 60, 2013; Oil on canvas, 200 x 160 cm

The Red Road: Not Simply Nostalgia for Nostalgia

What first strikes those seeing Chen Ke’s works is probably the bright keynote red; they probably also notice the frank, bold strokes and configuration, as well as the leitmotif images redolent with nostalgia. “Chen Ke’s bright red paintings depict Utopian scenes from New China - born of revolution - in its early period of construction from the late 1950s to the early 1960s”. This positioning seems to represent a general impression of one type of viewer - but when you are closer to Chen Ke’s Red Road, some impressions become more real.

Chen and I are of the same generation; we both belong to the post-70s cohort and while there is a culture of nostalgia attached to the 1970s, history is never as simple as the calendar. Who can articulate clearly, what is different about the mood of nostalgia felt by those of the post-70s generation, and that of older or younger generations?...they only vaguely encountered this Utopia via their parents, but they do not really understand it, because they were beginning to want more freedom, even though still filled with certain faith and beliefs. On campus in the 1970s students were still exploring “ideals” and “values”, but the ideals and values of that time could no longer provide simple answers, so we need to ask: What do college students today discuss? The world in these intervening twenty years seems to have changed beyond all recognition. In a sense, people are not nostalgic enough, and they tend to be too forgetful. Today people regard life twenty years ago as remote as though it was two centuries ago, but the problem is we still live in the one world, and our art is still touched by it. The essence of art might be nostalgia, at least in the sense that art often encourages people to look back, and feel concern that for the realities of life that are often forgotten in the rush of city living.

I really agree with Chen’s words: “The real charm of each artist’s work cannot be captured by a camera and placed in an album. Only deep in the artist’s studio do we realize why they are able to create the works they produce and to understand their inner conceptual values”. We rush to attach conceptual labels to so many things, but painting always reminds us to directly confront the image itself and preserve its inherent genuine awe. The post-70s art world has been a distinctive field for contemporary Chinese art and the post-70s generation have been the main force in this field, but they are also quite unique and difficult to classify. They are more rebellious than any tradition, but in confronting fashions they are also somewhat “nostalgic”.

Sometimes we believe too much in time and history, but to build a history of tradition using writing we sometimes also need to be forgetful; the tendency to remind everyone about those big events and “ideas” is virtually forgotten when we respond to smiling faces, joy, anger, or sadness. We tend to remember a reform or a campaign from a few decades ago; while we might have personally experienced the events, sometimes it is also easy to forget: Why are we happy at these times? How was I able to live then? If we lose such “nostalgia”, or more precisely, lose this reflection on our existence, then our lives will imperceptibly become barren; we cannot lose hope and we cannot lose its significance, just as the “red road” cannot lose the bright sun.

In this sense, we are seeing Chen Ke anew, as we gaze at the red road motifs and the culture and language they convey. I believe that there are many kinds of roads and ways along which we can achieve excellent art, but every way entails its own particular determination and piety. Excellent contemporary art requires an ability to honestly and sincerely reflect on one’s self, and at the same it is essential to fully mobilize the gaze of the audience, so that when we are gazing at the artist’s works, we are also able to feel that we are gazing at ourselves. If we gaze intentionally, we can see the richly expansive force released by the language of Chen Ke’s red series of works, and the first forceful visual impact with which we are familiar is followed by that gaze as our eyes adjust and relax, so that we can return to a familiar calm. Even the use of a palette or a pair of shoes as ready-mades can serve at the same time as a cultural metaphor and visual subversion. Intense emotions are subtly hinted in his depth of detail, either when seen closer or at a remove. While momentarily inattentive, one can also feel part of the tranquillity of the world that exists in the art, but once stimulated by the confronting symbols the viewer will suddenly be directed to a realm of broader meaning. Or, as the artist himself said: “In my works I can have two identities; at times I am the ‘observer’ of my own painting and at times I am a ‘participant’ in the picture itself”.

Yet all this is not so mysterious; in taking the road back, we find people on the road. We believe that this road points somewhere, and we believe that this road points in the direction of paradise. But having experienced life, we value the road as a process rather than as an outcome, and we can believe in the road itself and believe in life itself as long as we have faith. Today the post-70s remain a generation with faith, and Chen Ke at least is such a person and such an artist; he maintains an inner constancy through the myriad changes of life. He lives his own life and walks his own road, but has never given up his hope and faith, and I hope that his art will travel far as it continues to reveal its wonder and bedazzlement.

Shao LiangTranslated by Dr Bruce G. Doar

About the exhibition

Exhibition Dates: 24/05/2014 - 25/06/2014

Opening: 24/05/2014, 3 - 5 pm

Courtesy of the artist and Red Gate Gallery.