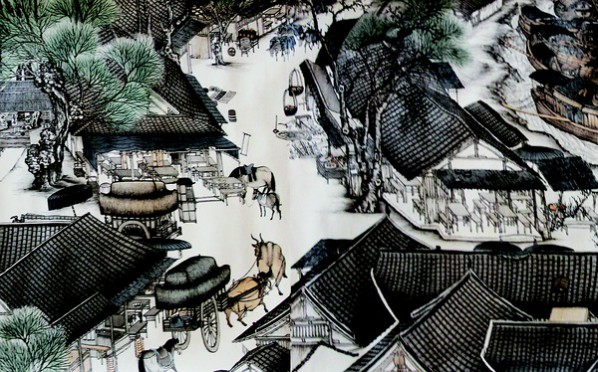

Bailyn-Galenou once made a sharp comment on the Documenta 12, Kassel, in 2007, he said one of the highlights of the whole ducumenta was “The Long Scroll of Chang’an Street”: “We have to notice that Lu Hao doesn’t simply record the change of the city, but fills the screens with poetic flavor and hope. Perhaps his original idea suggests the possibility of a tradition being continued into modern times. Such a possibility can be covered with the style of painting, and also carried by every resident in the new buildings.”

The recent new Gong-bi is different from the one adhering to adapting ancient forms for the present-day in Mao’s era, on the basis of maximising and retaining traditional techniques, a lasting appeal and literati interest so it adds content to contemporary life, while he has neither changed his natural curiosity, nor changed the style of drawing of the appearance of things. Lu Hao’s new Gong-bi and the new Gong-bi paintings come down in one continuous line, but these are different to a great extent. His have a unique character that breaks the harmony of the painting, sometimes violently inserting the things that don’t belong to the category of Gong-bi in the painting.

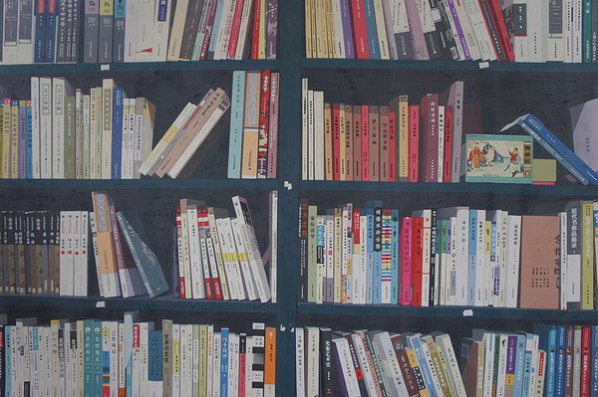

Lu Hao, “Landscape Series – Knowledge”, Chinese painting on silk, 200 x 150 cm, 2008

Lu Hao, “Details of the Riverside Scene at Qingming Festival without a Man”, Gong-bi on silk, 1000 x 50 cm

It is obvious that Lu Hao’s strategy is defamiliarisation. When Lu Hao defamiliarizes the objects in his paintings, we see the formal sense of Gong-bi as an art form, or the essence of installation art as a kind of art. In other words, he wants his audience to understand his work as art, rather than the means to achieve a particular purpose or as subservient to reality. He was known for “Flower, Bird, Insect and Fish” series installation in 1999, Lu Hao created many organic models of key historical and political significant landmarks in Beijing such as a flower pot, bird cage, insect shed, and fish tank. This installation helps us to pay attention to the most basic key element of spatial installation art: changing our perception of an existing space or structure. In Wu Hong’s words, “Flower, Bird, Insect and Fish” removed the political symbolism of the holy buildings like Tian’anmen Square: “The transparent structure of these installations remove the sacred atmosphere of the original building, thus exposing secrets”.

In Lu Hao’s recent works, especially his new Gong-bi painting, he strengthens his concern about reality. The local history of Beijing, the process of Chinese urbanization and marketization, the leisure and the traditional lifestyle rapidly disappear, these are all showcased tartly in the new work of Lu Hao. The spicy feeling is diverted from Lu Hao’s attempt to hide his concern about reality behind the “reality shown to you”. I would like to use “the reality shown to you” to distinguish the real mixed reality and the filtered reality removing the fresh but often ugly content.

Lu Hao, “Daily Life No.1”, Gong-bi on silk, 200 x 150 cm, 2013

Lu Hao, “Landscape Series – Drinks”, Gong-bi on silk, 200 x 150 cm, 2009

In the new landscape series by Lu Hao, we can see the whole shelf is full of Yanjing beer, and various other labels of Yanjing beer. What’s the difference between the painting and the famous Campbell’s Soup Cans by Warhol? On the surface of it, Lu Hao’s replication of the shelf follows the original idea of Warhol: the supermarket’s business culture is refined to the fake art so one has to use an artistic vision to view it. In giving it a second thought, we find that Lu Hao still continues to declare his loyalty to the scenery of Beijing. In another painting, Lu Hao draws a stall of children’s clothing in Silk Street in Beijing. Silk Street is well known in both China and abroad, as though it was first known for cheap fake brands, now it is crowded by stalls and customers. It is a “business card” for Beijing, which is the “reality shown to you”, but Lu Hao’s photographic realistic copy helps us pay attention to the unsustainability of China as the workshop of the world. It can’t be denied that behind the reality, among a large number of materials, goods and people, boundless desires are continuously produced, exchanged and sold.

Through “defamiliarisation”, Lu Hao does not only show reality as the “reality shown to you”, but also breaks the modern myth of the new Gong-bi. For Lu Hao, skill is not only a choice of style, but also a kind of ethical choice.

About the artist

Lu Hao was born in Beijing in 1969, graduated from CAFA in 1992, and currently he lives and works in Beijing. He was appointed as the curator of the Pavilion of China of the 53rd Venice Biennale in 2009. He served as the foreign art consultant for the city government in Paris, France from 2009 to 2013. He was appointed as the only designer (and the first one since the factory was established) for global limited edition Ferraris in Italy in 2009.

About the Exhibition

Curator: Xu Gang

Duration: January 18 - March 28, 2015

Open time: Monday to Sunday, 10:00-17:00

Venue: We Gallery

Courtesy of the artist and We Gallery, translated by Chen Peihua and edited by Sue/CAFA ART INFO