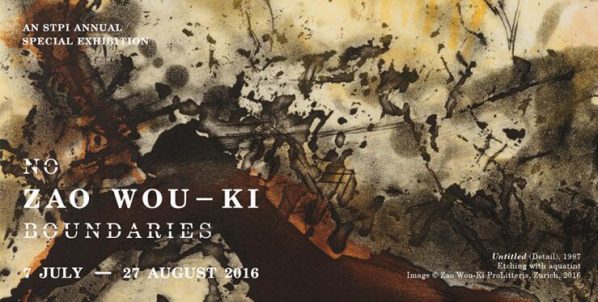

STPI Gallery is pleased to present ‘Zao Wou-Ki: No Boundaries’, an extraordinary selection of over 40 prints, ink works, watercolours and paintings by the late French-Chinese abstract painter, on loan from a private collection. Charting the evolution of Zao Wou-Ki’s illustrious career from 1950s to the early 2000s, this concise retrospective highlights how the artist renewed his art through various forms and influences, unveiling in particular, a lesser-known side of the painter whose printmaking practice reflects his ceaseless creativity and growth. Like his paintings, his prints display the strength, versatility and development of one who straddled two traditions to produce seminal works of great art historical value and significance.

Notable for having pushed boundaries in his lifelong quest for new artistic forms, Zao’s impressive career spanning decades is marked by an oeuvre that unites the cultures and aesthetic traditions of the Orient and the Occident on a single painterly surface. This synthesis, which caused the critic Wim Toesbosch to contemplate the ambiguous placement of Zao’s visionary and cultural identity—whether one ought to refer to the maestro as “[the] most Western of all Chinese painters…” or more rightly so as “the most Chinese of all Parisian painters,”—distinguishes his prolific body of work as one that stands peerless today in the world of 20th century Chinese contemporary art. As the artist once said, “Everybody is bound by tradition. I am bound by two.” This lifelong narrative of reconciliation across cultural boundaries, between old and new, is foregrounded in the exhibition, and is one that will resonate soundly within the deeper consciousness of audiences in Singapore and around the world.

Zao Wou-Ki (b. 1920 – 2013) left Shanghai for Paris in 1948 on a journey that would radically expand and sharpen his unique artistic voice. Abandoning the Chinese ink of his youth, believing it had “lost its creative impulse since the 16th century because the works thereafter were stifled by repetitive and mechanical imitation of the Tang and Song dynasties,” Zao gravitated towards the styles and forms of the Western visual aesthetic heralded by figures such as Cezanne, Matisse and Picasso, and the Abstract Expressionists like Paul Klee. Particularly intrigued by the latter’s “half representational and half surreal” world, Zao pined for a poetic and imaginative visual language of his own, setting him on a pursuit that would eventually lead him to discover abstraction within Chinese calligraphy and primitive forms of writing, adapt these motifs and surpass these traditions by forging Western and Eastern approaches.

It was with this penchant for experimentation that Zao maintained a permanent fixation on the medium of print and paper, alongside his extensive repertoire of paintings. Following his arrival in Paris, the young Zao attended courses at the Grande Chaumière, where he marveled at the technique of lithography with the printer Edmond Desjobert, with whom he would share an enduring partnership as he pursued printmaking in the great tradition of French peintre-graveurs (“painter-engraver”) throughout the rest of his career. And even within the processes of printmaking, Zao’s habit of tweaking methodologies never escaped.

In a 1961 interview, the artist admitted that he has nonetheless “gradually rediscovered China” in the process of his reinventions, and that “paradoxically, it is to Paris that (he) owes this return to (his) deepest origins.”

“Indeed, he needed to disengage himself and break free from every ritualized process among which the act of painting in ancient China was trapped. It was essential, in order to recognize himself finally and freely as a Chinese painter. The imprints left by his early childhood, for a while faded, became more prevalent with age. The earliest memories, all the legacy of hereditary culture, imperceptibility returned from his innermost being,” wrote French historian Georges Duby, in the foreword of the catalogue for the artist’s retrospective at the Museum of Fine Arts of Kaohsiung, Taiwan in 1996.

“Zao’s return to tradition, rather than a simple emulation of style or form, took place at the higher level of his philosophical and aesthetic outlook... Zao also displays superb craftsmanship in his ability to meld such calligraphic lines with the free application of colour… With his understanding that Chinese art derives its basic visual elements from the energy of the brush, Zao injects calligraphy’s rhythmic energy into his work. His lines leap and fall with great sweeps of energy, or rest within the lingering appeal of graceful curves, so that the fundamental symbols and gestures of his work acquire the same dignity and grace as great calligraphy… His great breakthrough was to reinterpret these aesthetic elements… Nature and the universe, the great energies of life, and the flow and shift of time became his subjects; his paintings build up spaces that are highly abstracted and hold deep philosophical implications.” – Christies, Lot Notes.

On the artist’s influence, New York Times journalist Paul Vitello noted that he was “embraced by artists and influential cultural figures in Paris” such as close friends Alberto Giacometti, Joan Miró and the poet and painter Henri Michaux, who wrote a series of poems about his work. His other close friend, the former president of France Jacques Chirac wrote the preface to his catalogue for his first major 1998 retrospective in Shanghai and appointed him to the Grand Ofcier de la Legion d’honneur (Legion of Honour), France’s highest recognition in 2006. His paintings, which are in major international public art collections such as the Museum of Modern Art, the Guggenheim and the Tate Modern, have sold for up to two million dollars in the market. Art dealers referred to him as the highest-selling Chinese painter of his generation back in 2011, with painting sales totaling up to USD90 million. To date, Zao remains one of the most commercially successful Chinese artists, raking in large demands for his work after his passing in 2013.

“My paintings become an indicator of my emotional life, because in them I revealed my feelings and state of mind with no inhibition whatsoever,” said Zao. As Specialist Julia Grimes noted, Zao’s given name “Wou-Ki” (or “Wuji” in the standard Hanyu Pinyin Romanization used in China), means “no boundaries,” which fittingly describes his “insistence on a personal and aesthetic identity in the face of the vagaries of borders and time” that has propelled his art forward.

About the exhibition

Date: 7 July – 27 August 2016

Venue: STPI Gallery

Courtesy of the artist and STPI, for further information please visit www.stpi.com.sg.