The sea is a bequeathed existence from the heaven, bestowed with its own legends and civilization. While the seas segregate the continents where we inhabit and seek survival, they are also the means that keep us connected. Our conception of the sea manifest on three levels: the natural, the legendary and the desirable. These three parameters derived from its physical existence give dimension to two phases that characterize our relationship to it: one we relied on for survival, and the other causes our bloodshed. The latter was inferred to as what Michel Foucault claimed as modern history marked by the “establishment of continental communication” of mankind. The boundlessness and enigma of the seas have always stimulated the human desire to explore and overcome it. Since the beginning of the Age of Discovery, the seas have lost their tranquility. The establishment of world order of the modern era is commenced with the Europeans’ designation of the first global meridian line in 1494, known as the famous Treaty of Tordesillas.

This treaty was a bilateral agreement signed by Portugal and Spain two years after Columbus’ discovery of the Americas. Based on this treaty, for the first time, the Europeans demarcated world power on the continental plates. It is an event of great historical significance, because of the meridian line delineated in the Treaty of Tordesillas, geopolitics of the modern world order surfaced. With which, a dual structure of geopolitics began to emerge on the horizon: where the global space coincided with social spaces of the people living on the continents (Lydia Liu). Thereafter, Great Britain issued the Navigation Acts in 1651 that further appealed to the explorers, unveiling the thirst for foreign colonies and their resources amongst the European nations. Henceforth, politics and distribution ratio of interests related to the seas officially entered people’s field of knowledge. Ni Jun is fascinated with the sea. He is even more passionate about geopolitics, and the research on the discourse of power constituents, centers and struggles engendered thereof. As a liberal intellectual and a conceptual artist, the works Ni Jun presents attempt to unveil a desire for the sea through its affect on the faces and in the spirits of those who have experienced it; the exhibition adopts events and objects related to this subject to liaise with the effects of people’s desires on the natural sea.

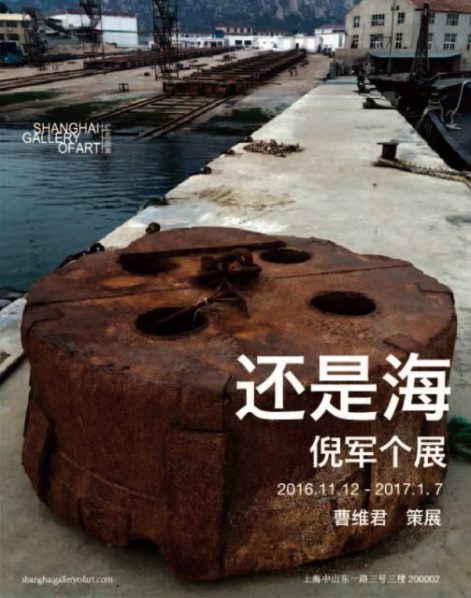

The exhibition, The Deep Blue Sea is put together through merging original research, and its content comprises of objects from primitive sites, video, installation and paintings. Ni Jun takes his thoughts, the signifier/signified of his artworks, and his interpretations on history and the human experiences and the issues confronted, accurately threw them into the dark mundane world around us, or adopted them into the discourse of what the sea represents in general. The sea is not only a vessel, it’s also a door, where you may enter and then exit; it represents boundaries, points of inception and end. Like the process of our lifetime, this is a key in understanding the meaning of Ni Jun’s work and the central goal of this exhibition. The artist creates and appropriates various elements in this vast funnel, through filtering and precipitation, what eventually comes out is not only his anxiety, but also a skeptic’s doubt on human nature and civilization. Ni Jun’s deductive analysis of visual culture, and the outcome engendered by the dwindling power and civilization in traditional notion in today’s global discourse, the degree of which these two aspects synchronize is not necessarily the goal of this exhibition, rather his aim to search for a new perspective with the viewers on the real and the abstract conceptions of the sea, to find ways of interpreting it in a broader sense. In particular, in grasping a more logical perception of China’s conditions in the present and for the future – by which to contemplate whether it should choose the old path of becoming the great powers or to improve with wisdom by taking different approaches to development.

Ni Jun’s works are often related to the impression and rhetoric of the sea. He’s been observing the absence, or at least, a disconnection on the subject of the sea in Chinese painting, at the same time, torn by amassing artistic subjects and power of discourse of the sea beyond China. In particular, he’s perceptive of the common issue confronted by humanity through the “Lurongyu 2682” massacre, and the mentality of the illegal Chinese human trafficking came forth on the capsized “Golden Adventure” off the shore of Queens, New York, and the fate of the Turkish life boats floating on the Mediterranean, in deciphering the future of the planet. Besides his numerous paintings, he has read a letter of protest (video) out loud on Israel’s bombing of Palestine at the front gate of the University of Liege in Belgium, as well as, taking a large number of photographs documenting his personal observations and unique ways of life. A native of Tianjin, Ni Jun has been living in the portal city since his childhood, later in his adult life, he traveled and lived in New York, Los Angeles, and off the shores of the Mediterranean. Today, he’d like to tell these tales of loves and passions through one’s desire for the sea, to reveal an artistic aura depicted through the sea and human figures in interacting and sharing with his viewers. At the Shanghai Gallery of art, Ni Jun will tie the sound of steam whistles on the Huangpu River to the heart beat of every visitor, allowing them to come out again from Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, and turn toward the desire for the sea, to confront fear and to forever embrace the sea.

In recent years, from the perspective of visual analysis, Ni Jun has also explored the deadly battles under the Atlantic and Norwegian seas between the German and British Navy During WWII, diving into the long historical occupations of sea space, a deeply rooted impetus of the European ideology… this may have an inseparably Lacanian psychological relevance to the film Spirit of the Sea, he watched with his mother in his early childhood. He may have been piecing together these fragments in his mind since a very young age, the boats, the sea, people, their desires, the realm of knowledge, sailing and the power of weapons, the glory of cohabitation as well as techniques on the battlefield… all of which provide a deeper understanding through the “Lurongyu 2682” incident presented in this exhibition.

About the exhibition

Dates: Nov 12, 2016 - Jan 7, 2017

Opening: Nov 12, 2016, 17:00, Saturday

Venue: Shanghai Gallery of Art

Courtesy of the artist and Shanghai Gallery of Art, for further information please visit www.shanghaigalleryofart.com.