Since the ’85 New Wave, Chinese contemporary art has been searching for and establishing its own complete contemporary visual cultural system. Chinese artists either misappropriated or borrowed from the mature Western theories, schemas of contemporary art and perhaps the use of realistic painting to transform Chinese painting inherited from the traditional Chinese literati elite class is replaced by contemporary ink or starting from the Chinese classical cultural traditions, techniques to seek its transformative connection with contemporary art.

On November 4, 2016, “Omens: Recent Works by Wu Jian’an” opened at Beijing Minsheng Art Museum and is curated by the famous art historian Wu Hung. Fan Di'an, President of the Central Academy of Fine Arts, attended the opening ceremony and stated that, Wu Jian’an was a prominent representative in the field of contemporary art focusing on the creation of traditional resources. Over the years, he has focused on the studies of ancient Chinese mythology and history, traditional philosophical concepts and image generation methods. The exhibition takes “ancient Chinese legends” as a theme, to conduct a new transformational experiment on the tradition and contemporary.

“Omens”: Contemporary Proposition of Ancient MythsThe exhibition consists of four series of works, including the large-scale color paper-cut collage of “The Birth of the Galaxy”, installation of “Three King Tomb”, to the “Daydream Forest” which further breaks through the previous creations, and the series entitled “Omens”, which was produced by 9 animal specimens, showcasing a total of nearly 40 works.

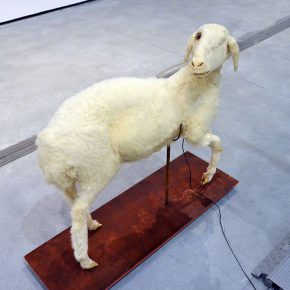

The exhibition provides an opportunity to connect with the mythical world with contemporary thinking. The “Omens” series consists of nine animal specimens: a Tiger with nine heads, a giant elephant with four ivory tusks, a spotted deer with eyes in its buttocks, a goat with a long bushy beard, a sheep with only one eye, a horse that is covered with motifs, a goose with a long neck, a fighting rooster, a horned rhinoceros, ... these animals are “pregnant with an unusual image”, which is like the beasts narrated in “Classics of Mountains and Seas”, seeming to herald the mysterious information of a glimpse of the future. The dimension of “omens” does not stop here and the weird creatures are also instruments that can be played – when each specimen makes a sound, it is an integral “omen” integrating in form and sound; when nine instruments gather to play music, it is also a symbol of the unexpected group scene produced by the gathering of various “omens”. At the same time, the introduction of performing brings the “omens” the color of an artificial design, and “omens” gradually become the result of conscious organization.

The animals of “Omens” are spread over seventeen tree-shaped brass sculptures – in the “Daydream Forest”, both are intertextual, to form a complete scene and narrative, being interrelated to “Omens”, Wu Jian’an said that, “it might be the result of omens or it might bring about an omen”.

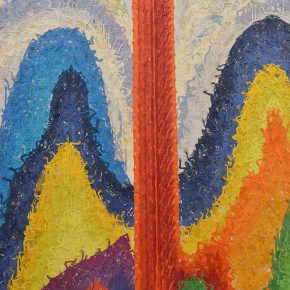

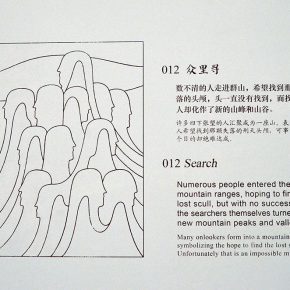

Xing Tian is a character of Chinese folk myths and legends, “A Classic of Mountains and Seas • Stories of the West” records that, after Xing Tian’s head was cut off, he continued chasing his enemy non-stop like a monster, and he represented a brave and unyielding spirit. The exhibition "The Birth of the Galaxy” is about the story of Xing Tian, and it took 4 years to create. Twelve more than two meters long paper-cut and collage works are hung side by side, it is formed by layering and collaging countless tiny, individual “Xing Tian” and other characters from the “Classic of Mountains and Seas”. “Innocence”, “Eliminating Outsiders”, “Killing Intent”, “Beheaded”, “Rare Treasure”, etc., …Each picture has an independent textual story, and also forms a mountain range. In the last piece of “Searching”, people who were dissatisfied with the Yellow Emperor’s tyranny, hope to find the lost skull, which is the evidence of a republic that had once existed. This is another symbol of Xing Tian given by the artist. In the work of installation “Three King Tomb”, is placed with three heads, indicating the truths that are hard to found. The lost heads are impossible to be found and it will disappear in the sea of historical truths.

Contemporary Transformation of Traditional LanguageWu Jian’an is keen to explore the transformation and breakthrough of Chinese traditional language and the contemporary context, and we can see a large number of multi-artistic faces which cross ancient and modern in his works. Starting from his first solo exhibition “Daydreams” held in 2006, “The Heaven of Nine Levels” in 2008, “Several Layered Shell” in 2011, “Transformation” in 2014, “Transformation: A Tale of Contemporary Art and Intangible Culture Heritage” in 2015, and “Ten Thousand Things” in 2016, … whether it came from the myths and stories rooted in Chinese history, the origin to inspire the birth of the drama, or indulging in the complex creation of Chinese folk elements such as paper-cuts, shadow puppets and the rich artistic languages hasten the artist’s evolution of personal style, so that it creates a unique shaping methodology with constant exploration.

“Chinese contemporary art might have a variety of forms ... It might be part of a worldwide trend in art, and might also be influenced by Chinese culture, Chinese art traditions, including folk art traditions, ancient visual technology, visual culture and many other legends, mythological themes ... from which to find inspiration, these factors are placed in a contemporary context, the contemporary visual environment will be re-interpreted and re-created.” Curator Wu Hung said that, “Wu Jian’an’s imagination has always operated simultaneously in multiple dimensions. Likewise, his works also simultaneously expand the viewer’s artistic imagination in various directions.”

How to Make a Breakthrough in Chinese Contemporary Art?As early as 1988, the National Art Museum of China had presented an exhibition of installation “A Book from the Sky” by Xu Bing, the modern paper-cutting art exhibition by Lv Shengzhong, in addition to many artists such as Gu Wenda and Qiu Zhijie who were engaged in the experiments and trying to introduce traditional Chinese visual schemata into contemporary expressions. Indeed, the combination of Western art concepts and Chinese traditional culture can provide a “differential expression” in the context of contemporary art, resulting in unique cultural thinking, which makes Chinese artists find the fulcrum of value in the identification of self-cultural identity.

Take the “Transformation: A Tale of Contemporary Art and Intangible Culture Heritage” by Wu Jian'an in 2015 for example, he took the folk opera story “White Snake” as a clue, contemporary art was involved in the intangible cultural heritage research, in cooperation with the masters of shadow play, to form a re-interpretation of the local tradition from a “conceptual” level. In this sense, the “Transformation” exhibition does not only advocate the display of the result of the subject of “contemporary art is involved in the intangible cultural heritage research”, offering a possibility for the productive protection and development of the Chinese intangible cultural heritage, and also gets rid of the re-creation of the inflexible “Chinese tradition”.

However, how to help artistic creations get rid of imitation or reproduction of traditional Chinese culture? It is noteworthy that under the great trend of globalization, whether the “re-creation” or “reconstruction” is dedicated to the advocating of Chinese traditional culture it will weaken art, its “contemporary” character and will create “different” Chinese “traditions” in the eyes of the West only to become a novelty in the Western discourse? Perhaps these are the “omens” which we need to be alert to and think of.

Text by Lin Jiabin, translated by Chen Peihua and edited by Sue/CAFA ART INFO

Photo by Lin Jiabin & Beijing Minsheng Art Museum