Cursory Script, Color, and Collage: Wei Jia’s Reinvention of Ink Painting

By Robert C. Morgan

To spend time looking at the works of Wei Jia, whether on canvas or xuan paper, offers an immanent and intensely rewarding experience. While his point of view as an artist remains committed to furthering the legacy of Chinese art, he is clearly aware of his exposure to Western styles as well. This exposure has further strengthened his commitment to working within his own tradition. There is little doubt that Wei Jia’s intuitive, focused, and meticulous maneuvering of ink is distinctly informed by his on-going practice both as painter and calligrapher. This practice takes its inspiration taken from the great poets of the Tang Dynasty in the eighth century and from the painterly methods used by Sung Dynasty masters from the twelfth century. In this respect, the art of Wei Jia follows in a traditional line, as he captures the three-fold essence of the inimitable Chinese literati: calligraphy, poetry, and painting.

This line became evident during his early studies at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing in the early 1980s. Since coming to the United States with his wife, the artist Lin Yan, after graduating with his baccalaureate degree in 1984, his adaptation of gouache pigments in relation to ink painting emerged from techniques he acquired as a graduate student at Bloomsburg College in Pennsylvania. The combination of ink and gouache offered Wei Jia a unique point of view, another means of perception, and an ineluctable combination of feeling and thought that goes far beyond the normative status of tradition.

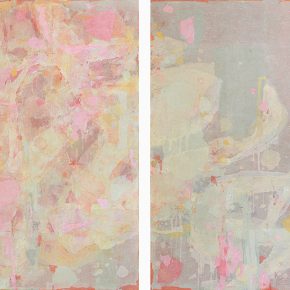

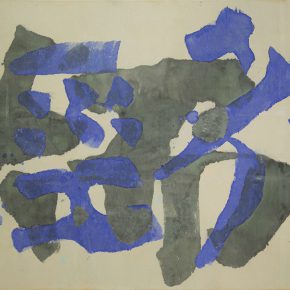

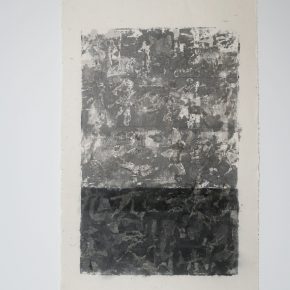

The light in Wei Jia’s color is pervasive in the sense that it reveals what is hidden in the art of traditional calligraphy: the manner in which the artist actually applies pigment and collage with xuan paper that he cuts and tears with his hands, laying it down over previously drawn marks and gestures both in art and gouache. One might refer to this method as a kind of multi-medium approach in which the process of painterly and calligraphic applications, coalesce with the layering of torn and cut shards of xuan paper procure a mode of contemplation. Through this highly attenuated and deeply felt process, the retinal act of seeing color comes into the surface as the pigments move and bounce in an optical way from one section of the canvas to another. Wei Jia is clear about his perspective – that there is nothing illusory. The layering of the strokes and lamination of fragments of xuan hold infusions of colors – often, but not always earth tones – that create a complex variety of textures and cursory interruption of ideographic

forms that ultimately defer the possibility of meaning in any strict literary sense. Rather the cursory ideographs are dissembled, torn apart, weakened, before they are rebuilt and revitalized into a new visual structure. Here the artist emphasizes pure feeling on the surface of the canvas or within the complex mix of ideographic fragments in black and white on large sheets of xuan. In either case, whether on canvas or paper Wei Jia inaugurates a new species of expression taken from his tradition, rather than appropriated from Westernized expressionism. This heroic, yet subtle process, moving from poetic inspiration to a visual construct given a dense tactile resonance, over time, has been pushed and pulled into place.

Given that Wei Jia begins each day with more than an hour of writing calligraphy after a light breakfast with tea, it is no surprise that his manner of writing has clearly come into his art. There is little he can avoid it. To write the ideogram persistently over time, over days, weeks, months, and years, suggests that something is being gained in the process of being lost. For the artist, this paradox is ineluctable and definitive. To gain is to lose, and to lose is to regain the necessary strength to continue one’s task. To regard this action as a continuum, as an uninterrupted process allows the eye and mind to relieve the tension of a purely spatial opposition.

This seemingly contradictory approach to thinking and writing in the act or writing and painting is perfectly consistent from a Chinese point of view. What goes away comes back again, and what suddenly comes into the forefront of thought may temporarily disappear. It will ascend and then descend, moving from one place to another. In the process, the artist Wei Jia discovers his own sense of time and his own method before returning to create another work, a new distillation, binding ink and gouache on xuan and canvas. This is the place where memory precedes history and where history is retrieved from the darkened past.

Returning to the application of color, Wei Jia is clear that color is an integral idea in his work, not simply a decorative adjunct. The question may arise as to the brilliant of some colors in relation to the more equalized sobriety of the earth tones. While often seen as separate from one another in China, especially as they pertain to the popular, more decorative approach to art in contrast to the literati landscapes of the late Sung Dynasty. Within the current atmosphere of cultural globalization, Wei Jia is less interested in maintaining this separation than in generating new ways and means on how they might appear together in the canvas within the texture of one surface.

From his point of view, color is removed from the symbolic realm used by Chinese artists, both fine and decorative, in the past, and is now open to experimental license. Why not combine the two? Just as the categories of high and low art have come into close proximity, why not bring somber and bright light together within an array of color that speaks of the present?

Whereas the artist has recently remarked in his typical Ch’an manner that his work has no point, I am inclined to both agree and disagree. While the terms of the unconscious mind would be a foreign concept to a Chinese artist, the feeling of nature is not. For the Chinese artist, nature is the source from which the qi (energy) moves from one body to the next, whether in plants, animals, or humans. Concurrently, it exists in all the four basic elements: earth, fire, air, and water. The qi yun is associated with “emptiness” or wu-nien (without mind) as found in higher states of meditation or within the unexplained leaps of enlightenment found in these paintings. Once this is understood, Wei Jia is correct: There is no point. But, from a Western perspective, there are occasions when making a point about no point might be useful as a way of coming to terms with the deeply profound insights the artist has revealed as in the works that comprise this extraordinary exhibition.

___________________________________________________________

Robert C. Morgan, Ph.D. writes frequently on the work of Chinese contemporary artists. He lives in New York City and teaches in the Graduate School of Fine Arts at Pratt Institute and the School of Visual Arts. Author of many books and exhibition catalogs, he is a painter and New York Editor for Asian Art News and World Sculpture News. In 1999, he was given the first Arcale award in Salamanca (Spain) for his work in Art Criticism. In 2011, he was inducted into the European Academy of Sciences and Arts.

He has curated over 80 exhibitions of Modern and Contemporary Art in various galleries and museums worldwide.

About the artist

Born 1957, Beijing, China.

Lives and works in New York and Beijing.

EDUCATION

1987 M.F.A. Bloomsburg University of Pennsylvania, Department of Studio Art.

1984 B.F.A. Central Academy of Fine Arts, Department of Oil Painting, Beijing

SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS

2017

New Exhibition Wei Jia Schmidt/Dean Gallery, Philadelphia

2015

Cursive Script,Color, and Collage, NanHai Art,CA 2015

2012

Wei Jia: New Work, Schmidt/Dean Gallery, Philadelphia, 2012.

2008

Wei Jia: New Paintings: Calligraphy, Collage, Crossculture, Cheryl McGinnis Gallery, New York, October 14 - November 22, 2008.

2007

Wei Jia: Made in China, Schmidt/Dean Gallery, Philadelphia, 2007.

2006

Wei Jia: Made in Beijing Forward Slash New York, China 2000 Fine Art, New York, October 2006.

SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS

2015

Lin Yan & Wei Jia: A Garden Window, Kwai Fung Hin Gallery, Central, Hong Kong, November 17 - December 16, 2015 (catalogue)

Sovrapposizioni Di Immagini, Casa Dei Carraresi, Treviso, Italy, June 20- July 1, 2015

2014

Experience China Chinese Contemporary Oil Painting, Dadu Museum, Beijing, 2014.

Tales of Two Cities: New York & Beijing, Bruce Museum, Greenwich, May 3 - August 31,

Oil & Water Reinterpreting Ink, The Museum of Chinese American, New York, April 24 - September 14, 2014. (Catalogue)

2013

New York Beijing Here There, Yuan Art Museum, Beijing, October 24 - November 5, 2013.

China Style, Dadu Museum, Beijing, opened on October 19, 2013.

2011

Asian Variegations, Chelsea Art Museum, New York, December 8 - 16, 2011.

Giving and Receiving, CU Art Museum University of Colorado, Boulder, U.S.A., April 8 - July 22, 2011. (catalogue).

About the exhibition

Dates: May 27th – July 8th 2017

Venue: Schimidt Dean Gallery

Courtesy of the artist and Schimidt Dean Gallery, for further information please visit http://schmidtdean.com.

Exhibitions

Exhibitions

Exhibitions

Exhibitions

Exhibitions

Exhibitions

Interviews

Interviews

Information

Information