This story begins with a cat. One day in 2015, dust blanketed an asphalt road in Beijing. The cars flew by, as the sunlight shining on the gravel and asphalt reflected a few pinpoints of light. White guardrails separated two lanes with different speed limits; everyone hurried onward, all with their own worries and concerns. In the center of the road was a dead cat—I don’t know how many times it had been run over—but all that was left were some tire marks and a bit of fur.

The traces of this story had been weathered, and all that was left on the ground was a vague, abstract pattern, like rolling out a small carpet on the asphalt. Time had worn away its original appearance. The initial bloodiness and misery had disappeared, so the viewer became indifferent, not sad. Most of the passersby did not care about this life—it was “worthless.” No one knew what this cat experienced and encountered.

Zhao Zhao depicted this vestige in chalk, like an expert at the scene of a murder trying to figure out the final posture of the deceased. This scene was not a chance occurrence, and it was certainly not an isolated incident. In the ensuing few years, Zhao Zhao continued to see similar circumstances in different places. Accidents and indifference, rules and collisions always play out on the roads; it’s just that the protagonist is always replaced.

Past tragedies always become hazy with temporal and spatial distance, and their emotional imprint is uneven due to different viewpoints and moods. If the temporal and spatial distance are short enough, we can still approach the original appearance of the truth. If this distance is long enough, the tragedy’s brutality and shock recede as its form changes, transcending our clear visions to become abstract dirges with aesthetic implications. The ability to always remember tragedy and the ability to change as a result come from the tradition in human civilization that reveres the defense of justice; the two are inseparable. Many times, when a tragedy takes place, there is always some indifference, righteous injustice, or avoidance of responsibility and fear of the violent among us. As time passes, these reactions become instinctive habit; they become coping mechanisms, allowing you to numb yourself and ignore it. This happens everywhere, in reaction to news from right around you, or from some distant place.

Mottled traces and chalk mists are the only threads in this story. The deterioration of life, regardless of its cause, is enlightening. Three years later, Zhao Zhao remade the shapes that he had recorded—the images of the flattened cats—in metal. As if commemorating what he saw, he needed to leave evidence that would not disappear. Comprised of four materials—glistening brass, reflective stainless steel, dignified black steel, and chimeric blue steel—this once soft fur has been transformed into extremely hard fragments, which are inlaid into the asphalt surface that Zhao Zhao set. Several thousand fragments of different materials and sizes constitute images of more than 20 cats, arranged in different places around the exhibition hall. They seem like a chart for an isolated island, sometimes connected and sometimes cut off by the asphalt, shattered into countless submerged reefs. They are like tombs, pebbles, or clusters of stars in a black Milky Way.

If you come to the exhibition hall at sunset, the massive asphalt surface has a silent radiance. The reflective shards are completely pure. The light shining through the top windows, hazy and solemn, draws the eye to the floor. However, in this moment, the sky seems closer and more solid than the earth.

As you wander through the exhibition hall, across the fragmented floor, every turn of your body or focus of your gaze makes the scene change in a way that cannot be replicated. Light, perspective, time, distance, and different emotions imply that you have waited for centuries, but you can’t sense death in the next instant. Fragments of copper and iron, pressed into the black ground, seem to approach immortality. However, as day shifts into night, and clear skies are obscured by rain, life becomes short and empty. This is both a prayer and a spell.

The exhibition site is like a Mass. At the Last Supper, the wine and bread replaced blood and flesh. The form and story of the cat point to a broader metaphor; the historical information, individual growth, and meaning of life that the cat represents is situated within a surge of past and present.

In 1838, Prussia laid the first modern asphalt road in Hamburg, which became a landmark and symbol of the expansion of industrial civilization. Several thousand years before this, tar was used as a binding agent in many ancient civilizations, in the Great Wall of China, the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, and the Roman roads in Pompeii. Roads linked the modern and the traditional, the cities and the wilderness, the center and the periphery. From Hamburg, asphalt roads divided the world, and asphalt was carried to lands that people had never previously traversed. Parts of the world without modern roads were considered backward and barbarous.

Cats are mysterious animals. They can really read people, they travel at night, and they excel at ambushing their prey due to the pads on their paws; their occasional foolishness and indolence mystifies their owners. However, the majority of the cats that are night travelers in the cities and ambush artists in the wild are stray cats. Their behavior is mysterious, they mate freely, and they often live in corners that man does not notice. They don’t like rules; they wander through streets and neighborhoods in search of food, independently confronting urban dangers that they have never known.

Therefore, for the cat, the asphalt road is a strange place. Here, the evaluation of time and space, rules and freedom, opportunities and risks, recognition and indifference, changes completely. The road was a trap for the cat. An independent cat obviously cannot deal with the common rules of modern society. This conflict is stark, like the countless progressions and regressions in history or a duel between the powers that be and the individual. One side is omnipotent and fighting nature, while the other side is weak and wild. Asphalt roads govern areas, dividing social classes, types of growth, and orientations of the sun. When confronted with entirely unfamiliar rules and systems, even nature’s most ferocious animal has no way to compete. In the end, steamrollers and mechanical hardness flatten the imprint of every claw growing out of their foot pads, so that no blossom-shaped prints are left in the asphalt.

Laying and conquering every distant stretch of road seems to add fuel to the revolution of modern civilization that humans have extolled. Whether they are called miracles of distant antiquity or modern industrial marvels, they imply that human civilization has “triumphed.” Behind these public and collective triumphs are countless individual choices, encounters, pains, sacrifices, and final memories, all of which become supplementary conditions for the collective. These supplementary conditions are never random.

The dead cat is a symbol of these supplementary conditions. The sacrifices of individuals that were once lively and different are unworthy of mention in the face of fanatical collectivism and in the myths of this nation and this people. This symbol points to an individual’s triviality and despair, not a miracle that a challenger has achieved; it is disparate resistance, a bystander’s indifference, and a future without a future. These familiar stories are like the moment of death, where your mind is clear but cannot be expressed, in a time when the conscious and unconscious are melded together.

Reality will not be resolved in art, but it provides us with a moment to bridge fact and perception. Here, the brutal, bloody tragedy is transformed into another solemn yet hallucinatory perception. It conveys real information mixed with beautiful form, revealing everything. Art compels viewers to face tragedies that truly existed, but that they were unwilling to see due to the limitations of ethics, aesthetics, and customs; here, these things cannot be avoided.

In this transcendental moment, death is an experience of the eternal; the vision of death covers all areas of experience. We temporarily forget to despair and forget about the helplessness of being unable to change anything. The beginning of the story, about the cat that couldn’t follow the rules, becomes a model, but one that is flattened into powder. The silence of death is so great, it seals the silence of naivety. We see glistening gold, flying blue sparks, and hard brown rocks between the sky and the road; they are the supreme forms of the natural world—an eternal beauty. But this is also just a moment; we are then drawn back into contemplation, sinking into a closed, naive reality: the story of a cat, or the justice of a blade of grass.

Text / Cui Cancan

About the artist

Born in Xinjiang, 1982. Zhao Zhao graduated from the Xinjiang Institute of Arts, 2003.

All along Zhao Zhao was making work with a subversive appeal of its own, keens on raising challenges on the reality and its traditional practice of art form through a various art media. Zhao Zhao is known for making sculptures, paintings and installations which examine the power of individual free will and the dynamics of state control. Zhao Zhao’ s works attest to and touch on the awareness of a generation faced with dramatic change. Constantly confronted with the subject of world oppression. Notions of threat or risk are regularly present in his works, referring to the life he lives both locally and within today’ s global context, as a method of questioning the historical impermanence in our contemporary society.

He is very reflective on how concerns of the collectivity co-exist with the individual’s daily expectations and dreams. His provocative, multidisciplinary artist practice has garnered him international attention in recent years, includes solo shows in galleries such as Alexander Ochs Galleries (Berlin, Germany), Carl Kostyál foundation (Stockholm, Sweden), Roberts & Tilton (Log Angeles, USA), Chambers Fine Art (New York, USA), Lin & Lin Gallery (Taipei), Tang Contemporary Art ( Beijing, China ), CAAW ( Beijing, China ).

He has received the support from many international institutions, among which are listed MOMA PS1 – The Museum of Modern Art (New York, USA), Tampa Museum of Art (Florida, USA), Pinchuk Art Centre (Kiev, Ukraine) , Groninger Museum (Groningen, Netherlands), Museum of Asian Art (Berlin, Germany), Padiglione D’ Arte Contemporanea (Milan, Italy),Premi internacional d’art contemporani diputació de castelló (Castelló, Spain), Minsheng Art Museum (Shanghai, China) and UCCA (Beijing, China).

The Project Taklamakan of his was elected as the background picture of 2017 Yokohama Triennale Poster and catalog. At the same year, he was appraised as Top 10 Chinese artist by CoBo and obtained the award nomination of Chinese annual young artist in 11th ACC (Award of Art China) and one of Modern Painters “25 Artists to Watch”.

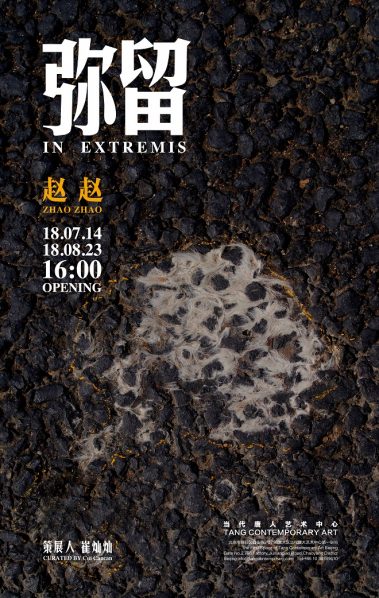

About the exhibition

Dates: 2018.07.14 – 2018.08.23

Opening: July 14, 2018, 16:00

Venue: Tang Contemporary Art Beijing

Address: Gate No.2, 798 factory, Jiuxianqiao Road, Chaoyang District, Beijing, China

Courtesy of Tang Contemporary Art, for further information please visit www.tangcontemporary.com.