Let us take a look at Shougang’s history: In 1919, Shijingshan Steel Plant was founded in Shijingshan on the western side of Beijing’s Chang’an Street and was renamed “Shougang Corporation (Capital Iron and Steel Corporation)” in 1967. In 1984, Shougang first created the contract responsibility system and led a reform of China’s national steel corporations. In 1994, Shougang’s annual steel production was over 8 million tons and was ranked first in China... At it’s peak, Shougang had more than 260 thousand employees, over 120 subordinate units and plants, and was one of the biggest steel corporations in the world. Its legacy and development is undoubtedly the epitome of China’s modern industrial development. In the new era, Shougang followed the government’s call for decreasing and ceasing production and accomplished a great relocation of the mainstream steel process. The relocation cleared an area of 8.7 square kilometers at the Shougang Heritage Park in western Beijing which was awaiting re-planning. As a representative production line in the smelter system of Shougang’s production, the No.3 Blast Furnace was naturally chosen to be converted into the Shougang Museum. This was also the first renovation and refit project of blast furnaces in China.

In 1950s, writer Zhou Libo became affiliated to Shijingshan Steel Plant and based on the overhaul of blast furnaces, he completed Tie Shui Ben Liu, the first novel on the theme of steel industry in China. Later, other writers have come to Shougang as well, producing works such as Wang Zongren’s non-fiction novel Zhou Guanwu and Shougang. In the 1980s, the fourth series of Renminbi introduced 50-Yuan bills for the first time, which had figures of Shougang workers with white canvas uniforms, berets, and protection goggles. Today, such scenes have inspired artistic creations modelled on the past, and workers have moved out of the place that was once their spiritual home, only memories were left behind.

On September 22, 2018, an exhibition on the design and renovation of Shougang Industrial Heritage Park and No.3 Blast Furnace Museum opened at Saint Catherine Church in Venice. With various media resources being used, such as architecture, film, stage-set, graphic design, literature, projection work, documentaries, photography, Steel Home Still recreated the memories of Shougang, and at the same time, inspired the spectators on how to respond to urban regeneration in terms of collective consciousness, discourse and solutions.

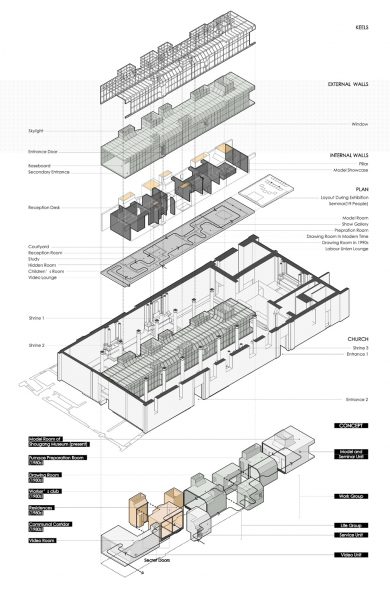

Spacial Design Concepts of “Steel Home Still”

Drawing Effects of the Exhibition

Drawing Effects of the Exhibition

As the main curator and chief architect of No. 3 Blast Furnace’s renovation project, Bo Hongtao has felt the characteristics of respect from the Shougang people and the diminishing importance of the steel industry in public discourse. He realized that a mere architecture exhibition was not enough to express all this, and gave up on the idea of purely showing the architectural renovation, instead he decided to reconsider the entire exhibition from a humanistic standpoint, on the eve of Shougang’s centennial in 2019. Similarly, curator Wang Zigeng’s perspective is “the narrative and organization of the exhibition is by no means neutral, and cannot be done without a discussion of values.” He wanted to turn the formalized architectural project to a retrospective and journey on place and memories. Thus the two hit it off, with a humanistic perspective as the basis and cooperation being common to both of them.

What is different from a conventional architectural or art exhibition, first of all the chief curators Wang Zigeng and Bo Hongtao were confronted with the materials, equipment, and productive tools from all historical stages in the preparatory office of the Shougang Museum. Thus the first and foremost question was how to turn these materials to an exhibition worthy to be visited.

Apart from being an architect, Wang Zigeng was also proficient in spatial narrative and expression. Before working at China Central Academy of Fine Arts, Wang Zigeng taught at the Fine Arts School of Beijing Film Academy, and was a consultant on historic architecture and environmental design in films. He has also been involved in a lot of influential personal work and exhibitions. In the interview by CAFA ART INFO, Wang talked about an exhibition he worked on while working for Atelier FCJZ in 2007, Wujianzao, which took on multiple narratives, and told a story of three distinct narrators in three silent films. The narratives intersect and complicate themselves, to the point that no one can distill it from the truth. He thought of the exhibition as a continuation of the concept of Wujianzao. For him, a single space needs multiple hermeneutic systems to expand the space for the reading of the exhibition. “Curating an exhibition with multiple layers of reading perhaps needs a good storyline, and it also needs to establish a connection between space, exhibited works,and the story line.”

Wang mentioned in the interview that, the curating team first wanted to present stories of multiple Shougang workers, but turned to fictional figures and stories after considering all the practical obstacles. Young writer Jiang Fangzhou was selected as the storyline writer for her similar past experience of living in a collective community. She was not foreign to the life of Shougang. In her memory, in national corporations such as steel corps, railway corps, etc., a corporation or even a department was a life circle in itself. People knew each other very well. Class difference seldom existed between them. Vertically, the life of their children often bore the shadow of the previous generation. The storyline that she wrote described a father and a son with generational antagonism. The son went against the will of his father due to his curiosity about the world. He studies abroad after taking the college entrance exam and then settled overseas. Then, through time travel, he went into a universe where he listened to his father, and took over his position as a Shougang engineer.

Different from the separate expression of multiple artists in conventional art exhibitions, the cooperation between architecture, theater, literature, multi-media and film teams resulted in a highly integrated and complete exhibition. Wang Zigeng and his team were responsible for the design of spatial installations, and built a series of montage spaces at the Saint Catherine Church. Its interior was divided into a mirroring pair of new and old drawing offices, control rooms, residences, activity rooms, union offices, libraries, nursery rooms, and other typical production and life spaces. The stage-set director Zhao Nali, who has worked on Sleep No More’s Shanghai version, was invited to be the stage-set art director of the interior of the installation. On top of the design of exhibition and spaces, the multi-media team, led by Fei Jun from China Central Academy of Fine Arts, translated the text by Jiang Fangzhou to visual effects that responded to the multi-dimensional spaces in the text.

Space Installation in the Exhibition

View of Exhibition

View of Exhibition

View of Exhibition

View of Exhibition

Fei Jun’s team creatively designed some mini-motion-projections onto old picture frames, televisions, studio desks, and newspaper, leading to some subtle changes that are only ambiguously noticeable, leading the story so visitors can make their own discovery. On top of the exhibition materials, Shang Lei, who had his debut as a theater director with this exhibition, translated Jiang Fanzhou’s text into a language that is operable through multi-media. The audio guide from either the father or the son’s perspective, with their respective angles, lead visitors into different spaces of the exhibition, and compliments or contradicts with each other, providing multiple readings for each of the pieces carefully exhibited in the venue. What is more, apart from the environmental sound in the scene, the multi-media team creatively interrupts the environmental sound in each of the rooms with Xinwen Lianbo News or Radio Exercises according to their respective time frame, serving to present the relationship between collectivism and individualism.

Video Work was screened on an old television

Group photo presented by moving images

Diaries presented by new media technologies

We explore the life of the father and the son back then in the exhibition...the father’s diary, drawings, the poker table where the father and the son used to play chess, their bedroom and study room were all carefully represented, from which we see the daily life of Chinese people in the industrial era. As if we are entering the old houses that we lived in, we seek to find past memories, futilely attempting to construct the stories of the past. The audience naturally engages with it, trying to grasp at an idea. Each room is different, yet each room has its own secret. Entering them would feel as if we are entering a special time and space, in which we become one of the protagonists. Wang Zigeng hoped to help an international audience, usually without the proper context, to understand the collective life of typical Chinese working people in the 1980s, through an immersive presentation. “I hope people will see that, an abstract factory consists of thousands and millions of specific families and individuals. I hope to bring the audience into real life and scenes through a tangible story, to evoke empathy with that specific time.”

In the past few years, immersive presentation was applied in theaters and exhibitions, and grew in popularity in China and overseas. The immersive presentation usually creates an environment that satiates the senses, evoking empathy through sound, music, video projection, etc. In terms of perception, it is exactly the participation of the audience that completes the artists’ work itself. One view holds that, while attracting the senses, the immersive presentation would fall culprit to mere “entertainment”. Obviously, Steel Home Still did not seek to please the audience, it instead was presented to the global audience with an individual, microscopic, empathetic, participatory form that inspires the desire of the audience to explore. At the same time, it invited understanding and empathy with sentiment, the relationship between the collective and individuals, and China’s modernization.

At the end of the exhibition stood the model of the No.3 Blast Furnace, with the excellent craftsmanship of the special effects team led by Chen Yijie. The model shows the contrast before and after the renovation. Thanks to the progression of the audience, the memory of Shougang park’s landscape and its life, represented by No.3 Blast Furnace, was gradually revived. As architect Amnon Rechter remarked, “the audience finally understands the preconditions and meanings of Shougang’s regeneration. It aims to revive the industrial giant of yesterday, and let everyone participate in its past, as well as share its bright and autonomous future.” As the title Steel Home Still suggests, the No.3 Blast Furnace Museum will continue to record the future Shougang and urban memory in a brand new manner.

Text(CN) by Yang Zhonghui, edited by Sue/CAFA ART INFO

Photo Courtesy of the Organizer