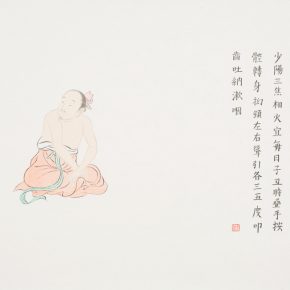

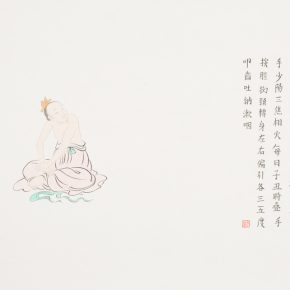

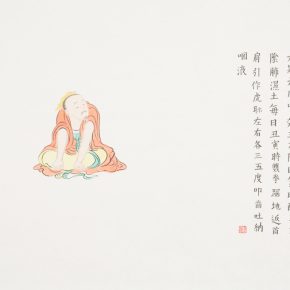

From January 18th through to March 30th, 2019, “Diagram of Cultivating Perfection: Wu Yi Solo Exhibition” is held in Shanghai XUN WAY art space. The exhibition mainly showcases the latest works of Wu Yi, Diagram of Cultivating Perfection series as well as his publications, prints, photographs and so on. Diagram of Cultivating Perfection is based on Chinese seasonal solar terms and he uses twenty-four figures to show the practices that ancient disciples of Daoism worshiped, and the key theme is about the harmonious relationship between human beings and nature, human beings and the universe. This series of paintings “integrate the morale of literati and health preservation which follows the rules of the months seem to be conversant with ancient learning.” (Quote by Gong Pengcheng)

Wu Yi is one of the few outstanding ink and wash artists in the field of Chinese contemporary art. From his latest works, we can clearly find the source of his materials: the literati portraits, the Dunhuang murals, and the woodcuts of the Ming and Qing Dynasties. Whether it is conscious or unconscious, Wu Yi has studied and discussed the three main trends of Chinese spiritual traditions in these works: the literati portraits series of Sages about Confucianism; the Buddhist figures of Epiphany about Buddhism; and the series entitled Diagram of Cultivating Perfection about Taoism. These three spiritual attitudes have become the soul seeking art in his practices. The wisdom of literati painting, the spirituality of Buddhism and the Taoist practice have contributed to his creation.

The characters in his Diagram of Cultivating Perfection are emphasized on the traditional Chinese male model which is a round, flexible, feminine body of man that is commonly found in erotic pictures, rather than the type of masculine body sought after by contemporary Chinese artists. This is a part of self-exploration conducted by Wu Yi: reluctantly revealing himself while satirizing himself.

According to his latest series of Diagram of Cultivating Perfection and his creative experience in recent years, CAFA ART INFO conducted an in-depth interview with Wu Yi.

I Where does the “faint Wu Yi”come from?

Zhu Li (hereinafter referred to as “Zhu”): The most interesting thing about your paintings and words is the leisurely and innocent temperament which is not as simple and light as they look. There are Eastern Zen and the freedom that you handle complicated matters with ease. First of all would you briefly introduce your learning experience?

Wu Yi (hereinafter referred to as “Wu”): My initial painting experience comes from the teaching of my parents. When I was in elementary school, I began to imitate the portraits of Russian sketches. I first painted the bones, then painted the muscles then painted the skin, which was painted from the inside out. The reason my parents taught me to draw was mainly because they wanted me to learn a special skill. At that time students graduated from high school went to the countryside. With the specialty of painting, I could “be drafted to” the city as early as possible. I never dreamed of resuming the college entrance examination in 1978 when the Central Academy of Fine Arts began enrolling students. In 1979, there was a training class for the art college entrance examination after the Cultural Revolution in Changchun Workers’ Culture Palace. When I was in the fifth grade of elementary school and I sketched with people preparing for the college entrance examination. At that time I completed the sketch of David. At the same time, I also liked to draw trains. When I was off school in the afternoon, I would go to Changchun Railway Station to observe trains. The blank pages in my elementary school books were full of paintings of trains. At that time, no one recognized the paintings. I didn’t seem to think that it was painting either. I painted trains since I liked them from my heart, and I felt that drawing was painting. Drawing sketches from plaster statues, sketching portraits and painting trains became the elements of my original paintings, which were parallel to each other. (Like now I create oil paintings, ink paintings, with different themes, parallel creations with different content, which are perhaps formed by the unconscious painting methods since my childhood).

My grandfather was a student of Mr. Jiang Zhaohe. He studied in Jinghua Art College in the 1930s. His paintings were profound and unrestrained, and he wrote using his brushes throughout his life. When I was in high school, my grandfather shared his knowledge of Chinese painting. It was a very pure knowledge of Chinese painting. But at that time, I thought that sketching was a basic skill, for Chinese paintings, especially the ink figures of Chinese paintings, the requirements for drawing are even higher. Moreover, everyone in that era was painting like this. (In retrospect, many of my grandfather’s opinions are correct. The basis of Chinese painting was not sketching. At that time, the understanding of the definition of sketching was that it was the basis of plastic arts. Then, the understanding of Chinese painting at that time was to mould characters on rice paper.)

Zhu: Someone told me that you excelled in drawing and you grasped western language when you were young. When did you start giving up on that language and looking for your own language?

Wu: I started to learn drawing and shape it into a three-dimensional space. In fact, the Chinese face is flat with only the nose being slightly raised when in profile. This set of observations and expressions that we have learned is suitable for expressions of Westerners. Sometimes, after painting the plaster statues of the West, when we paint Chinese people, we draw a lot of ups and downs on the flat face of the Chinese. This is why many Chinese painters prefer to paint Xinjiang people and Tibetans because they can correspond to the methods they learn when they represent faces. In fact, I have not given up on the language that I have mastered since childhood, and it is difficult to give up on it. It offers a lot of value to me. Even today, when I want to comprehensively portray a certain things or subject matter, when I want to be very “realistic”, this language will still help me.

There are some artists from my peers who did not start with drawing Western sketches, but from Chinese calligraphy and painting. However they have gradually shrunk in number over the years. I think that the previous generations did not draw sketches, but they had an extreme understanding of shape, spirit, and structure, and they expressed art in lines. This is a very difficult thing to explain. Sketching for me personally enriches the systems how I view the world and express the world. At some stage in my individual painting practice, it still plays a very important role and has an impact on the openness and pattern of my work.

Over the past few decades, my painting style has a lot to do with my experience, my age, and the strange things I encounter. My materials come from life, memory, history itself and even dreams. Some things that are very impressive in life are not necessarily painted, so that painting itself has very strict norms.

My Diary in Paris was my first overseas travelogue. The content was created in 2002-2003 and published in 2005. It has three meanings: The first is that I lived alone for 6 months abroad and it was a diary with words and paintings, which made me feel like I was living in Paris. The second is to read Chinese traditional paintings in Europe. The beauty and artistic conception of Chinese art are also very clear. Thirdly, after I returned to China, there was no exhibition of my experiences but the publication of My Diary in Paris, which clarifies my way in which the travel notes are recorded in the form of a travelogue in the future.Zhu: You once said, “People should paint in an experienced way when they are young, and they will paint in an innocent way when they are old.” Indeed, when you were young, your work introduced a sense of maturity, and as you grow older, your work gradually approaches children’s innocence. When many audiences are confronted with these paintings, they feel confused and happy at the same time. Many of the children in your paintings seem to be naive, whether that is intentional or unintentional, would you like to talk about the changes in your thinking in this process? What kind of painting do you think is fine and is it unnecessary to keep painting?

Wu: People need to find a certain contrast in their lives, which is no exception in art. When a presentation is too realistic, it often seems to be lacking in something. This is especially important for brush and ink. Because when we suddenly think that traditional paintings look good and want to read them, we will stare at the state of the painter when he was in his peak stage: such as the works of Huang Binhong and Qi Baishi in their senior years, and we often don’t care much about their early works. This phenomenon is also interesting.

Painting is actually a method for you to imagine and perform. Everyone has an individual way. I don’t think a painting can be perfect. As long as the core part is displayed, it can be completed. This core part refers to the expression of artistic conception.

Zhu: There is a “sense of paragraph” in your work. I have received several copies of your booklets, and a large book which is rarely seen. These “paragraphs” can be linked together, some are logical and some are not. It looks very loose and casual, and people who look at it feel very relaxed. This is very different from the larger catalogues that many artists like to print. These small albums, travel notes, and illustrations are also very elegant, and can be said to be an extension of your work. It’s unnecessary for books and paintings to be very big and comprehensive. When did this start to form?

Wu: I think art creation is a process of continuous accumulation. It has no results, and it is always a process. It is like comparing life to a journey. In recent years, the publications of my books have gradually returned to the functionality of books, which suits “reading.” First of all, the book should not be large and the content of my books were designed with rich texts, not just catalogues, reading material is the main focus. Large catalogues also need to be done, so that people have a clearer appreciation of the work itself, but emphasis may differ according to the stage.

I value the text (book) more than the exhibition, because the duration of exhibition is limited and the book is not, the works printed in my book have another beauty. The value of my text is independent. Since the publication of My Diary in Paris, I have formed this idea which continues to today.

Zhu: I found an interesting feature in the relationship between your painting materials and expressive language. The materials you mainly use are ink and wash on paper, as well as oil on canvas. You said that all your ink and wash paintings are about what you think as they satisfy your imagination, while all the oil paintings are drawn from life as they satisfy your vision. How and why such a division has been naturally developed?

Wu: I have experienced a long term artistic practices so that I have gradually found that oil painting if compared with Chinese ink and wash painting, is more corporeal, more accordant with my visual enjoyment, or in other words it can accurately record my intuition that is what I see; the natural attributes of ink and wash painting have a distance from Nature, and the expression of ink and wash painting is closer to human hearts. Surely it can represent the real world, but this will undoubtedly counteract its inner spiritual attributes. These two methods for me are complementary to each other, as they means the relationship between matter and mind.

Zhu: Actually, when you work on oil paintings, you seem to create them in a state of ink and wash paintings, as if you did not study the expressive techniques of Western oil paintings which serve just as a medium and tool for you, the key of your creation is still the observing and expressive methods of Chinese paintings as well as your own creative language. For example, you just paint intrinsic colors in your oil paintings and you ignore the environmental colors which you think might affect our visual experience. However, when we used to learn painting, we were told that the expression of environmental colors as well as the cold and warm relationship among colors, indicate the painter has a excellent sense of colors. However you have firmly stated that: you think the intrinsic color is the most beautiful. This is undoubtedly exciting in the Central Academy of Fine Arts where “gray is the most advanced color.” Would you like to talk about it?

Wu: I think that the intrinsic color is the most beautiful and essential, although I have experienced what you mentioned in my experience of learning. This is the indirect experience brought by western colors especially impressionist colors. Actually, before the emergence of Western Impressionism, many paintings and murals in the Renaissance and the Middle Ages were expressed by intrinsic colors, while traditional Chinese murals and scroll paintings were also expressed by intrinsic colors. During the color teaching in China over nearly a hundred years, most of us rely on Western experience instead of excavating the most basic and simple cognition of colors as human beings (whether from the East or West). Actually in plastic arts, the strength and beauty of form is the most important. The most important feature of Eastern and Western traditions is to emphasize the expression of intrinsic colors, which aims to emphasize the important of modelling and subordination of colors. During our color teaching and learning, the so-called feeling “good” or “bad” is actually not important at all as they are preconceived ways of thinking. The proposition of color should not be raised separately as it muse be attached to the modelling. Even a block of simple abstract color plays a decisive role. Therefore the intrinsic color in painting does not belong to the inherent beauty of Nature, but also come from the subjective creation of a strong artist, which is derived from reality but beyond reality.

Zhu: In recent years, you have created many works which seem to be quite “traditional”, such as the portraits of literati in the Qing Dynasty, twenty-four diagram of filial piety, some antique landscape scrolls as well as Diagram of Cultivating Perfection, etc. Where did they come from? What do you think is the revelation of these paintings for contemporary culture and life?

Wu Yi: Traditional texts in my opinion are quite realistic, as paintings are the most external things. Actually, the concepts and ideologies of Chinese have been formed thousands of years ago, what happened before still happen here and now, thus we inherit them. Therefore the “traditional” and “modern” concepts are inseparable from each other, which are completely different from Western comprehension.

Zhu: Your idea is very interesting—you “reproduce” traditions since you like them without alternations, and you feel a substantial satisfaction. This makes me feel that you have been always in pursuit of inner comfort and abundance, painting itself is not that important. It seems that painting is just a product you experience and feel the world in your practices.

Wu: The concept of “replication” occurred to Zhou Zuoren before, he used to copy ancient books every day, and he was called “Mr. Replication”. He did not explain much about it although he was not understood by others. He just said that, “ancients had written so well that I cannot surpass them” and so on. I copied from ancients but I intended to avoid my existence, i.e. “anatta”, to experience the charm of predecessors and correct himself.

Painting sometimes is not just for oneself, but it is a part of my life. We have so many things to do in our life, and life itself is the source of art. Painting might create a distance from reality, as it is something that feel futile and realistic at the same time, and further it can adjust the balance between “virtuality and reality.”

II The Clues of Two Generations

Zhu: On many occasions, especially during interviews, you often talked about “where you came from”, you always mentioned Mr. Lu Chen and Zhou Sicong, I can feel their significant influences on your artistic journey. I would like to ask you to talk about the art propositions of Mr. Lu and Zhou on art education and Chinese painting. In your opinion, what is the most precious thing they brought to you?

Wu: The influences of Mr. Lu Chen and Zhou Sicong on me are everlasting and profound. If I did not come across them at the Central Academy of Fine Arts, I might live and work in another state. Thirty years ago, I was a sophomore at the Central Academy of Fine Arts. Mr. Lu Chen suggested that accomplishments from both the East and the West should be cultivated at the same time, and he emphasized the artistic expression that was not classified by painting category. His perspective was unique at that time but the status quo of Chinese art education after 30 years has proved that Mr. Lu’s proposition was very forward-looking.

Zhu: What do you think of the current environment and current situation of Chinese painting and ink and wash painting? If being different from the predecessor artists and teachers, what do you think is the most important aspect when you are teaching?

Wu: It can be said that the backbone of contemporary ink painting is influenced by Mr. Lu Chen and Zhou Sicong. The diversity in the expressions of ink and wash languages at the moment proves that now is the most dynamic period that ink and wash paintings show their fascination. I teach in the Mural Department of CAFA and I do not teach ink painting. Although the ink and wash state is very active, there are still many uncertainties, including my own artistic practices, as the application of my creative state to the teaching will bring many unfavorable factors, so I instruct the traditional copying class with line drawing. And ink painting requires students to slowly comprehend in the practices of their lives. (But most of the teachers from art colleges will choose to teach the professions they are good at, which is beneficial while bringing about drawbacks. I often discuss with the students about some unknown fields and new trends that they might bring to art education.)

III Diagram of Cultivating Perfection

Zhu: Why do you want to paint this series of the Diagram of Cultivating Perfection? What is the key theme you want to explore in this series of paintings?

Wu: The key issue of my discussion is about the harmonious relationship between man and Nature.

Zhu: The relationship between ancient Chinese and Nature, and the universe, the Chinese Taoists have developed the inspiration methods and self-cultivation principles that are adaptive for the atmosphere of four seasons, what kind of inspiration will they provide for contemporary life?

Wu: The self-cultivation principles of ancients were based on their rich experience while they embraced with Nature for a long time, which were naturally accumulated. Along with the quick speed of modern society, it also has its practical significance for modern people and it is everlasting.

Zhu: If we carefully observe this series of paintings which are full of flowing energy, it has a sense of humor, and it is consistent with that kind of interest that you reveal casually in many paintings. Is this an instinct or is it a natural expression of your temperament?

Wu: Life is often accompanied by humor and entertainment, and in such a state as well, human functions can be released to the utmost extent, and one can constantly feel the beauty of the world.

Text by Zhu Li, translated and edited by Sue/CAFA ART INFO

Photo Courtesy of the Artist