Tang Contemporary Art presents Old Tales Retold, a solo exhibition for Peng Wei curated by Wang Min’an in the gallery’s first Beijing space. This is the first presentation of Peng Wei’s new work since her solo exhibition at the Suzhou Museum in 2017. In addition to Peng Wei’s classic series ‘Letters from a Distance’, ‘Migrations of Memory’, and ‘Good Things Come in Pairs’, she also presents more than thirty works including Old Tales Retold, a massive forty-meter-long scroll that took her four years to create, her narrative series ‘Seven Nights’ and ‘Peep’, and the installation Material World.

Coexistence and Role Models: Peng Wei’s Seven Nights and Old Tales Retold

— Curator: Wang Min’an

Peng Wei uses two methods to tell two different kinds of stories: one kind of story is related to her, to fictional stories that appear in her dreams, or to stories that come from her experiences; these are the narratives of ‘Seven Nights’. The other kind of story is historical, namely, the stories recorded in ancient Chinese books about women’s virtue, such as Paragons of Feminine Virtue or The Twenty-Four Filial Exemplars. This serves as the basis for her series ‘Old Tales Retold’. The two kinds of stories have a different nature(one comes from her own experience and one comes from written records), and their narrative methods are very different.

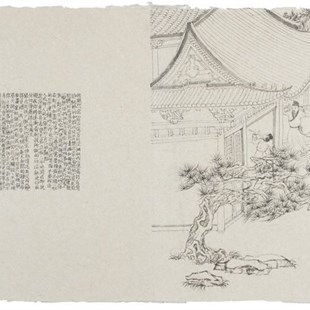

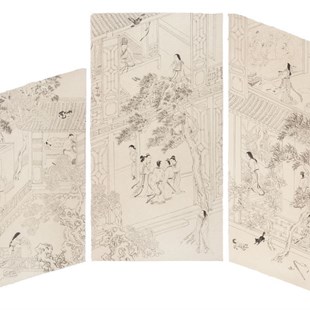

‘Seven Nights’ actually tells the story of a single night; these different stories are happening in seven different courtyard spaces on the same night. Peng Wei juxtaposes seven courtyard spaces. These are seven paintings of stories, but these seven paintings are obviously about spaces(courtyards). One could also say that the stories and spaces are closely layered. The stories do not take place along a continuous timeline; they are presented in juxtaposing spaces.

Although there are many figures in the paintings, Peng Wei makes space the protagonist. She pours her heart and soul into painting the roof tiles, doors, windows, railings, stairs, balustrades, corridors, and trees. She paints these architectural elements so patiently, transforming them into the most eye-catching parts of the paintings. Large areas of roof tiles appear in the paintings. Peng outlines the tiles in short, arched strokes, and these repeated, parallel arches make up a series of neat and simple rooftops. They are well-ordered and clear, overlapping and interlocking; even the winged corners echo one another. This echo also occurs between rooftops, between buildings, and between spaces in the paintings. The broad rooftops comprised of these numerous lines—Peng Wei, with her infinite patience, paints them one by one—echo and resonate with one another; they are certainly not constrained or unexpected. On the contrary, they linger at the top of the painting, creating a coincidental rhythm of curves, which makes the entire work seem even, stable, and harmonious. Although there are many complex spaces that adjoin, interlock, and proliferate, these spaces are not chaotic. Even if Peng Wei presents them in different paintings, juxtaposing them, she always has the ability to make her images neat and clean. She paints so many lines, but no line is a mistake; every line stands firmly in its appropriate place, and every line follows the overall arrangement and rhythm of the image. These steady, rigorous lines make these images stable and harmonious. As a result, these spaces make people feel comfortable—these are simple, neat, reasonable, and comfortable spaces, places where people could imagine themselves living and feeling content.

Peng Wei delineates the architectural spaces in the images, but it might be better to say that the buildings and spaces in her paintings are presentations of various kinds of line. The arrangement of these straight, arched, curving, and diagonal lines, as well as many parallel lines, are interwoven, overlapped, and connected to constitute the foundations of these spaces. Once she uses these succinct, clear, and fine lines to delineate a space, the space could not possibly be heavy. These are not close, dark, and sealed spaces; although these are purely monochrome paintings, the spaces woven from these fine lines are relaxed, easy, open, and transparent. These are not gloomy, dim secret chambers; they are bright living spaces for human activity. This space can be constantly infiltrated, spied upon, and opened up, linking these many different kinds of space and making them intensely visible. People’s secrets, worries, interiorities, and actions, as well as all these stories, can be revealed and highlighted in this space. Inside and outside, invisibility and visibility, secrets and truths are connected, entangled, and woven together here. This is a space, but it is not a space of prohibition and obstruction; this is a home, but it is not a home in which individuals and secrets are imprisoned; this is a building, but it is not a building that is indestructible or unreachable.

In these spaces, Peng Wei also paints large numbers of trees; their leaves are luxuriant, and like the rooftops, they cover large areas of the paintings. The breezes in the painting move the branches and pass through the empty spaces delineated by these lines. The trees and buildings have a special relationship. If the architectural space is transparent and open, the branches create shadows. They are concealing, and they form a contrast with the transparent buildings; they allow visibility to retain a certain invisibility. In contrast to the rectangular spaces of the buildings, the trees are curved, and in contrast to the stability of the buildings, the trees are swaying. In contrast to the openness of the buildings, the trees and their leaves are dense. The trees complement the buildings, covering them and moving them; they enrich the rooms and the buildings, diversify the monotony of the paintings, and bring complexity to the stories. Trees are another dynamic and soft architecture, another malleable space; the trees and the buildings, with their spaces defined by straight lines, are layered into another mixed space. The trees invade the buildings, rewriting them. To put it another way, the buildings give these large plants meaning as spaces and residences. It is the trees that make the building indistinct, it is the trees that tell the meandering story, and it is the trees that allow the people to linger or evade one another in their spaces, but it is also the trees that allow the wind to blow in the paintings. The trees put wrinkles in these stable painted spaces and cause ripples in the interior worlds of the figures. People are not enveloped by the dense space of these branches and leaves; the people come and go between them, infiltrate them, and appear among them. The figures’ faces shine between their shadows—the figures in Peng Wei’s paintings are closely interconnected with one another, but also with space.

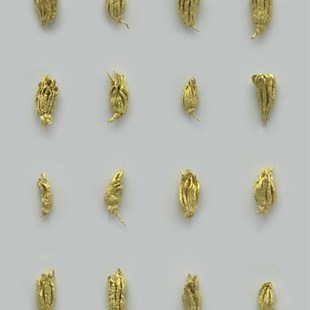

Several hundred years later, they are once again appearing in painting, but Peng Wei records them in pictures, not in words. She vividly presents them, but she also simplifies their stories. Her paintings are completed in just a few brushstrokes, because she did not painstakingly paint the details of their figures, and she did not obviously differentiate them. The clothing, faces, hairstyles, and even expressions of these women are very similar, almost to the point of being indistinguishable. Obviously, they are typical figures in a category, and Peng has not concentrated on their unique aesthetic attributes, when in the previous series, she painted so many beautiful details. She does not painstakingly differentiate the portraits; she simply emphasizes their different postures and gestures, elements that lie at the core of the stories. The original narratives in the ancient texts are focused on the gestures, and the drama develops around that action. The action takes place at the climactic moment in every short narrative text, and it is precisely these extraordinary actions that are the notable achievements. Peng captures the figures’ gestures and postures, freezing the action to immense dramatic effect.

These dramatic gestures turn these women into heroic figures. They seem tough and brave, which is very different from the figures of women in traditional painting; most women in traditional Chinese painting are weak, melancholy, and sad. They are yielding, and they often show their virtue only by yielding. However, the women in Peng Wei’s paintings similarly adhere to society’s requirements regarding virtue and respond to society’s rules, norms, and standards for women, but they are tough and unyielding, showing their strong will and stubbornness. With their determined and uncompromising actions, they express guiding principles of feminine virtue: being filial, chaste, and faithful. Thus, virtue is accomplished through strong will and fervor.

These spaces, buildings, and trees form another kind of architecture that is no longer purely the setting for the story. This new architecture is the catalyst for the story taking place; it is internal to the story, producing and weaving it. It is a critical component of the story. The protagonists of the story, these men and women with indistinct faces, are scattered throughout these spaces. They rely on space, using space to create their postures and gestures: sitting or lying down, chatting or entertaining themselves, sitting alone or gathered around a table, playing or fighting, waiting or meditating, leaving or arriving. They present everyday attitudes, or more properly, they present everyday life. They are living life, but they are not living in time; they are living in space. This is a fragment of their life, but it is also their eternal life. ‘Seven Nights’ is a night, a time, a moment. This life, which is simultaneously fragmented and eternal, is the story of their lives. People find it very difficult to identify the core of this story, its beginning and end, its strength and direction. Is it a tragedy or a comedy? People even find it difficult to identify its context and historical references. Perhaps this uncertainty occurs because these scenes came from dreams?

Peng Wei has said that she has painted the stories of several nights based on her dreams and her experiences. Whether they are fictional dream worlds or real experiences, and no matter how many details they contain, we are still seeing a universal state, a state of coexistence—a synchronistic coexistence between people. This coexistence implies that people with no bodily connection constitute a community, but it also shows that connected people can still maintain the most profound barriers. Every person relies on their own space, every person relies on space to determine their particular existential attitude, and every person is different, but from a transcendent and broad overview, the differences between them are not so significant; they all exist within the same vast space. They exist together. Their coexistence connects these seven different spaces, and these seven spaces allow people to exist together and connect together. People may say that this kind of story is not that dramatic, but if we look at it from above(many of the rooftops are seen from above), aren’t all lives, all people, and all stories—even if they are dramatic stories—equal in the eyes of heaven? Coexistence implies the existence of differences between individuals, but it also paradoxically implies that the differences between specific individuals have vanished, meaning that all things are equal. In Peng Wei’s painting, every posture is very specific, and every person is different, whether in action, emotion, or condition. However, every one of these differences, in an existential sense, is not a difference; they are just postures, people’s general living existences. They fill an infinitely vast space and eliminate all differences. They are the living games of existence: happy games and sad games, drinking games and sleeping games, chatting games and joking games, one person’s games and many people’s games. Every person engages in these specific games in a limited space and time. Yes, every game has different rules, but in essence, they are all games, and everything is seen as a game from overhead. Don’t Peng Wei’s antiquity-inspired paintings—and she knows all the techniques of a traditional ink painter—bear some similarities with the settings in computer games today?

‘Seven Nights’ presents a way for people and their spaces to coexist; they are groups of ordinary people living ordinary lives. The people in these paintings are anonymous, they are nameless passers-by in history, and their lives are ordinary and unremarkable. They are situated within this complex pictorial composition, and as individuals, they become ordinary elements in the paintings. Their ordinariness is consolidated and confirmed in this way, and they cannot be illustriously magnified in these complex spaces or heterogeneous images. Old Tales Retold is precisely the opposite; every painting in the series simply narrates a solitary individual’s extraordinary story. Old Tales Retoldalmost intentionally departs from the complex, varied, and interwoven pictorial compositions in ‘Seven Nights’. The imagery is simple, so simple it might be better to call them single portraits. In this series of portraits of solitary women(or two people including the woman), these women stand alone on a white piece of paper, the absolute presentation of a bare figure.

These women are drawn from famous ancient literary works on feminine virtue (such as P_aragons of Feminine Virtue_ from the Ming dynasty and The Twenty-Four Filial Exemplars from the Yuan dynasty). These women are not fictional characters; behind every one of them lies a shocking story. Based on these stories, Peng Wei imaginatively depicts these characters. She is just painting their portraits, removing their entire backgrounds. These women are all caught in a fit of passion, and the majority of them hold knives, preparing to harm themselves. It is precisely this unusual fervour and action that draws people immediately to them. Viewers focus their curiosity on them, studying them. These women become singular, extraordinary objects. As a result of this, they have been written into the history books, and as models, they have been inscribed and recorded in ancient books such as Paragons of Feminine Virtue. They have been recorded as moral models for women.

Perhaps this is precisely what sparked Peng Wei’s interest in exploring these stories. Toughness, bravery, rigidity, and passion (look at their knife-wielding gestures!) are naturally signs of rebellion, but how do they fit into the framework of standards and virtues that dominated society? Which is also to say, how can we reconcile conventional virtue with a fervour that breaks those conventions? How have these women’s rebellious and passionate actions made them role models for women following the rules?If we return to the original texts, we discover that this fervor was self-punishment, and those deadly knives are directed at their own bodies. The women’s violent actions are cruel torments of themselves. They are deemed virtuous because of their self-mutilation, self-destruction, and self-sacrifice. These female “role models” are affirmed for their self-destruction. Their intense fervour is a self-destructive fervor, and their toughness is a self-sacrificing toughness. Those books on feminine virtue are simply odes to women’s self-destructiveness. This kind of female fervor is not critical passion directed against the rest of society; it is not directed against men, or against society’s moral dogma. Peng Wei is re-writing these stories and re-painting these women, and of course she has a strong woman’s critical mentality. She removes the background behind them and directly and nakedly describes them in order to unflinchingly, thoroughly, and directly observe and expose this artificial female mythology. This mythology of feminine virtue is constructed around women’s self-sacrifice. These women are not models of virtue because they are conciliatory, humble, compromising, and obedient; they must take it a step further. They have to sacrifice themselves, make themselves feel pain, destroy their appearances, suffer humiliation, and mutilate their flesh. Only in this way can they become exemplars, and only in this way can they be written about and immortalized as role models.

Peng Wei is rewriting these stories today, but of course she is not merely critiquing a historical myth. Has this myth vanished today? What do these female role models of the past mean today? How have past values and ethical concepts survived today? Peng Wei asked these questions, and as she simplified these stories, she also muted her evaluation of them (a contemporary woman’s assessment of ancient women). She painted the fervor of the figure in the painting but concealed her own passion. She simply awakened them from their historical slumber, placing them in the contemporary moment. She brought them back to life, actualizing them and presenting them in the current time, and allowing them to speak and perform now. If these women were never questioned in the past, Peng attempts to test them in the present. When these large portraits of women are hung in the exhibition hall, viewers are curious because they lack background information. It’s no wonder that these paintings compel people to inquire, recollect, investigate, and reflect. This forcibly pulls history into the present, creating a violent collision between the two. This exhibition is a landscape of this collision and shock.

Here, we see a woman artist’s perpetual concern for women, or the presentation of long-standing women’s issues in a new way: How should women act? How should women gain their autonomy? How are women written about, recorded, evaluated, and presented? What kinds of instructional models or behavioural demonstrations do women see? In essence, these are still questions of gender politics, and these questions don’t have answers, but past models are certainly being challenged. Perhaps, it is only when these models are challenged, when the female myths underpinned by the dominant texts of the past are challenged that new possibilities can unfold. Old Tales Retoldquestions a women’s painting tradition(if one exists)using a specific pictorial mode, but it is also the reconsideration of the ancient relationships between text and image(and the relationship between text and image has always been an interesting subject). More importantly, it questions a tradition of women’s models for life (a tradition that certainly exists). These women’s actions seem intense, but Peng Wei gives their eyes a hint of hesitation and sorrow. Any resolute role model will always quietly evince something soft.

About the exhibition

Dates: 7 September–25 October 2019

Venue: Tang Contemporary Art

Courtesy of the artist and Tang Contemporary Art, for further information please visit www.tangcontemporary.com.