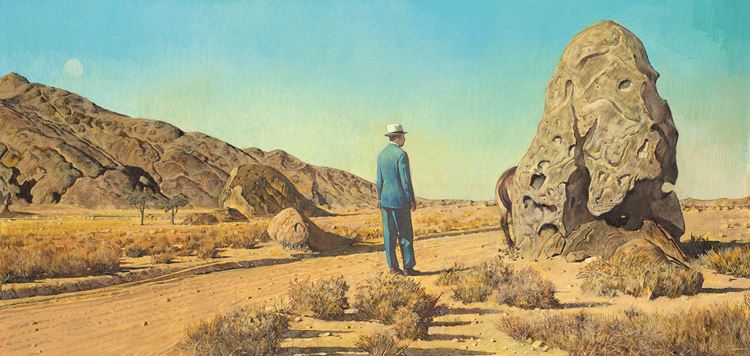

Wei Dong, Dismounting a Horse to Look at a Rock下馬觀石圖 (2018). Acrylic on Canvas. 34.5 x 71 cm. Courtesy Hanart TZ Gallery, Hong Kong.

Curatorial Statement

I imagine in Wei Dong’s art an image-eating glutton who delves into the innards of a silent picture and relishes every morsel of flavour hidden in the pictorial details, and delights in uncovering secrets that are never intended in the first place. This is perhaps the reason why things of the world get painted to be turned into pictures: it is to satisfy the lust for pictorial images, so that this inexplicable drive can be turned into concrete passions and fantasies, and perhaps eventually bring enlightenment.

The seductiveness of Wei Dong’s paintings is laid bare on the face of the canvas, as though any allegory or symbolic reference exists simply for satisfying the artist’s passion for images. Wei Dong draws his references from classical art and things of everyday life; when he was a young man his passion was for Chinese old masters, but since emigrating to the United States two decades ago, he has developed a love of western classical oil painting and its iconography. Wei Dong’s landscape paintings of recent years are purportedly a tribute to 10th century Chinese shan-shui (‘mountain-and-water’) painters, when in fact they are western landscapes painted from the perspective of shan-shui.

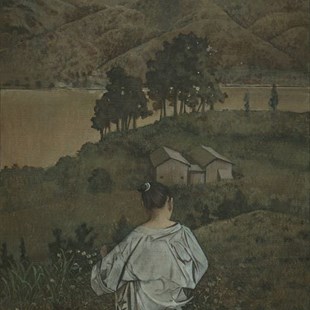

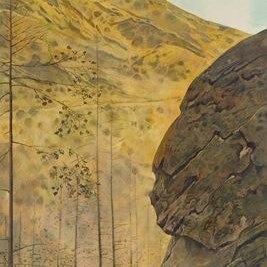

The change in painting medium transforms the ways nature is being perceived. One can certainly find shades of Song-dynasty masters in these pictures, just as one also can see the influence of wood-block book illustrations from later dynasties. However, the more one studies these landscapes and the more one moves with the rhythm of Wei Dong’s brushwork, one increasingly becomes seduced by the way shifting sunlight caresses the material surfaces of rocks and the way his colours transform the movement of clouds. In Wei Dong’s sceneries, the dynamic movement of the mountain ranges of the Song-dynasty masters is miraculously brought to a standstill, and the eternal silence of a world of material presence grasps the heart of the lover of images. Wei Dong’s oil painting ‘landscape’ arrests the world in motion and turns it into an object of philosophical speculation, and that is why the artist would present us with a man dressed in a formal western suit, who contemplates the vista in front of him as a metaphysical mystery. Unlike Zhong Bing (4th-century author of the first thesis of the Chinese art of shan-shui), who would dwell in the mountains and drink their elixir, Wei Dong’s thinker stands apart from the natural world.

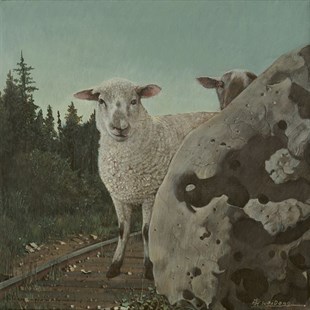

Wei Dong’s landscape scenes and his erotic figures appear to be two completely different kinds of paintings. However, their approaches to spectatorship are very similar. Calm and still, like a freeze frame in a film, they stop-action the dynamic experience of life, and turn it into a spectacle for contemplation. When held static, both the landscapes and the delusional erotic narratives are transformed into visual myths by this devotee of images. His paintings variously evoke desire or guide us towards a reverie of nature; in some landscapes, the mysteries of nature’s life force are concentrated in the forms of magnificent steeds.

The horses in the landscape serve to emphasise the stunning beauty and mystery of nature. Whether painted as an object of rapt contemplation, or as wrestling with its trainer, the horse symbolises the beauty of an untrammelled life force. By contrast, a shanshui painting would never place its focus on a horse, or on the solitary figure gazing philosophically at the scenery. The fishermen or the scholars depicted in shanshui paintings roam the natural world, and they are the passing guests of the mountains and rivers. But for a gluttonous lover of images such as Wei Dong, there is no difference between shanshui ink paintings and oil landscapes. He is an aesthete who lingers on and savours the world of images; and whether gazing in rapt contemplation or roaming for pleasure, he is never far from the intoxication of the delusional and the poetic.

Picture Obsession

Chang Tsong-Zung, Mid-autumn, 70th year of the People’s Republic

Artist Statement

I remember during the 1990s it was fashionable to drink red wine topped off with Coca-Cola or Sprite. This gave the red wine a sweeter taste; it really was more delicious than it sounds, but also was very easy to get drunk on it. Westerners spent centuries figuring out how to extract the sugar content from red wine, and now we were putting it back in. But the raison d’etre of wine is to give pleasure, and so long as people are happy, it doesn’t really matter how they drink it.

Looking at the Southern Song artist Xia Gui’s painting Pure and Remote View of Streams and Mountains, I think of the heartfelt effort that painters of the Five Dynasties and Northern Song put into capturing the textures and contours of the true mountains and living trees of the landscape, using rich colours and flying white, and reaching a pinnacle with Ni Zan. I want to capture the flavour and mood of ancient paintings, playing with light and shadow on the canvas, trying to reconstruct the artistic conception of the ancients, secretly imagining that I am mysteriously sitting side by side with them, travelling along and looking at the water, sitting quietly and observing the mountains; and as long as it makes me happy, it doesn’t matter how I paint.

In front of me I see a glass of wine and a bottle of Cola, but I won’t be mixing them together. I also see a painting by Xia Gui and a canvas, and I am thinking that these can be blended together, so that they are both Chinese and Western, ancient and modern; and just thinking about it, I am already drunk.

Xia Gui, Red Wine and Coca-Cola

Wei Dong, August, late summer, 2019

About the exhibition

Dates: 27 September–2 November 2019

Venue: Hanart TZ Gallery

Courtesy of the artist and Hanart TZ Gallery, for further information please visit www.hanart.com.