From November 26, 2021, “Wu Yi: Prague”, “Wang Yuping: Nominal Age: Sixty” and “Cai Lei: Metonymic Liminality” were displayed at Song Art Museum in Beijing. With the topics of these three exhibitions corresponding to the basic elements of place, time and space, the narrative logic of the three exhibitions is well connected and also provides evidence for observation and research on individual cases of artists.

“Prague”

For his solo exhibition entitled “Prague”, it indicates previous travels by Wu Yi while presenting the observing perspective of daily scenes by the artist.

One afternoon in summer 2013, Wu Yi flew to Prague after watching the Czech film Kráska v nesnázích (Beauty in Trouble). Over the last few years, he has visited this ancient Eastern European city many times. Wandering through city-center streets and country villages, he painted everything from cafes to female figures; he has always been meticulous, observing everything. These paintings are modest in scale, recording what he saw in these small, ordinary, or private corners of this world.

Exhibition View of“Wu Yi: Prague”

While in Prague, Wu Yi lived in the home of his friend Mr. Sklenar, on the fifth floor of 129 Pařížská ulice (Paris Street). During his time there, he immersed himself in the local life, like he had in Japan five years earlier—he felt as if he were living like a local. He went to parties at Czech friends’ homes and on excursions with acquaintances. He met artists, collectors, critics, gallery owners, and museum directors, as well as ambassadors and doctors. In Prague, Wu painted a lot of life model nudes; his models were people who work at a coffee shop, a gallery accountant, and a drama student. When he met their gaze, he naturally invited them to be painted, because they were so overflowing with life. He was very moved, touched by the beauty of life; this feeling gave birth to a series of photographs and paintings. There is a beautiful Czech version of The Dao De Jing, fully illustrated with details from Wu’s female nudes.

Wu Yi, The Hot Coffee, Oil on canvas, 40x30cm, 2021 Wu Yi, Ready for Take-Off, Oil on canvas, 60x50cm, 2020

Wu Yi, Ready for Take-Off, Oil on canvas, 60x50cm, 2020

In 2002, Wu Yi lived in Paris for six months. He painted more than 400 small travelogue works paired with text, which he published in the Paris Diary. The publication records walks, travel, and everyday observations in photographs, paintings, and texts; this project would shape Wu’s later travelogues.

Most of Wu Yi’s oil paintings are related to his travels. These sets of paintings are paired with stream-of-consciousness diaries of tiny details, capturing what he saw and felt as he traveled. Because of the limitations of travel, he paints exclusively in small formats. As Wu has said, his small paintings have two key characteristics. First, his small paintings capture the greatest possible ambience in a small space, and second, he uses sets of many small paintings to express what a large painting would be like.

Exhibition View of “Wu Yi: Prague”

Exhibition View of “Wu Yi: Prague”

Wu Yi likes to use round-tipped brushes when painting in oil, because they are a lot like writing brushes. These brushes give freedom to the lines, so that they can outline and refine expressions. His oil paintings seem “written”, because he brings calligraphic lines into the paintings. Wu Yi’s style of oil painting is characterized by this flattened modeling and use of inherent color.

Wu Yi, Mother and Daughter, Oil on canvas, 60x50cm, 2020 Wu Yi, Woman No. 1, Oil on canvas, 60x50cm, 2020

Wu Yi, Woman No. 1, Oil on canvas, 60x50cm, 2020 Wu Yi, Balcony No. 1, Oil on canvas, 60x50cm, 2020

Wu Yi, Balcony No. 1, Oil on canvas, 60x50cm, 2020

Wu Yi’s unique perspective of observation in this series of painting is reflected in that most of the characters in his works appear in the background or as a silhouette, without too much detail, or turning their back on the audience, or maintaining different dynamics when leaning over, or appearing in a hurry on street corners, all of which reveals the poetic and mysterious appearance of Prague.

“Nominal Age: Sixty”

According to the traditional Chinese method of calculating age, which counts the number of lunar calendar years in which a person has lived, Wang Yuping is turning 60 this year. Six decades is not just a length of time on this earth; it is a period of long reflection and an accumulation of technique and artistry. A great painter is not made overnight; his lines, strokes of color and compositions reveal his exceptional skill.

Exhibition View of “Wang Yuping: Nominal Age: Sixty”

Exhibition View of “Wang Yuping: Nominal Age: Sixty”

Wang Yuping is a Beijinger born and bred; he grew up in the hutongs of Baizhifang, in southern Beijing. He is a perceptive, nostalgic person who loves the city. In the 1990s, he was an important member of the New Generation, and he established a fresh, personal style with exaggerated, expressive figure paintings. Later, he turned his attention to roadside scenes in the old parts of Beijing and objects from his everyday life. When he paints streets and alleys, buildings with red walls and green tiles, and the silhouette of the pagoda in the sunlight, he gives them a distinct Beijing feel. In this exhibition, these scenes are brought inside, inviting the viewer to experience the painter’s everyday life. He paints himself, but he has also painted the people and things around him. Sofas, typewriters, books, magazines, sewing machines, shirts, hairdryers, lanterns, vases, headphones, wine glasses, teacups, hats, and basins—everything he sees, regardless of what he is doing, can be incorporated into his paintings.

Wang Yuping, Spring 2020, Acrylic and oil stick on canvas, 200x240cm, 2020 Wang Yuping, The Sofa with Black Armrest, Acrylic and oil stick on canvas, 200x160cm, 2021

Wang Yuping, The Sofa with Black Armrest, Acrylic and oil stick on canvas, 200x160cm, 2021 Wang Yuping, Mèng Yáng, Fēi Lǎo Tóu, Acrylic and oil stick on canvas, 200x240cm, 2021

Wang Yuping, Mèng Yáng, Fēi Lǎo Tóu, Acrylic and oil stick on canvas, 200x240cm, 2021

At the age of 60, Wang heard the truth with a docile ear. Sixty years is one turn of the sexagenary cycle, but more importantly, it is a time of self-reflection and introspection, so he painted a few self-portraits. The exhibition begins with his 1985 Self-Portrait and ends with two new self-portraits from 2021, entitled Nominal Age: Sixty.

His 1985 Self-Portrait is a large back-lit composition, with the figure’s face covered by several very dark shadows. Only the forehead and shoulder are suffused with a golden highlight. This aesthetic and painting method, as well as the fascination with intense contrasts between light and shadow, give us a clue to what would later become core elements of Wang’s unique personal style.

Wang Yuping, Self-Portrait, Oil on wooden board, 44.6x35cm, 1985 Wang Yuping, Nominal Age 60 No. 1, Acrylic and oil stick on canvas, 240x160cm, 2021

Wang Yuping, Nominal Age 60 No. 1, Acrylic and oil stick on canvas, 240x160cm, 2021 Wang Yuping, Nominal Age No. 2, Sewing Machine, Acrylic and oil stick on canvas, 206x240cm, 2021

Wang Yuping, Nominal Age No. 2, Sewing Machine, Acrylic and oil stick on canvas, 206x240cm, 2021

While his early works tended toward academic realism, his works in the 1990s shifted toward the use of bold, subjective blocks of paint, and even large areas of color. The simple differentiation of light and dark, the unpainted backgrounds, and the unfettered application of pure color are succinct, yet somehow show that he is expressing himself to the fullest.

Exhibition View of “Wang Yuping: Nominal Age: Sixty”

Exhibition View of “Wang Yuping: Nominal Age: Sixty”

In recent years, he has continued to employ large brushstrokes and pure blocks of color based on strong light and shadow, but he has become more interested in exploring the use of a line. His use of line is akin to writing; the gestures are profound yet natural, a pinnacle of artistic skill. His use of color has also changed markedly. His bright colors have become milder over time; the purity and brightness of his colors have gradually decreased. Grey tones have started to dominate his paintings, and his previously heavy, thick colors have become softer and more diluted. For Wang, painting is no longer constrained by the pressures of creativity; he has naturally internalized the medium as wisdom or profound artistry.

“Metonymic Liminality”

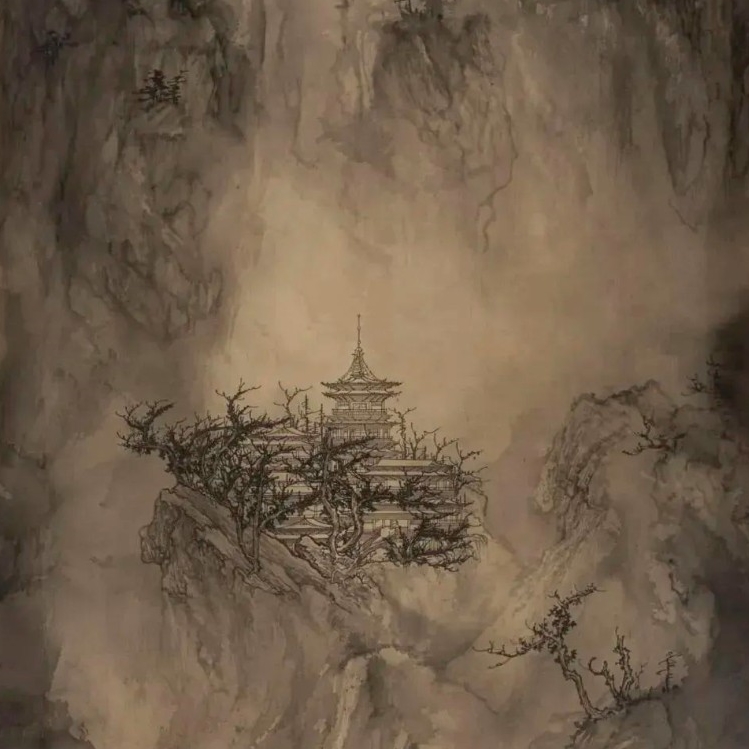

Being different from the paintings by the other two artists, Cai Lei displays a number of installations and sculptures in this exhibition. As the name implies, “up to the pavilion and remove the ladder” which embodies a physical relationship between an individual and physical space and symbolizes the artist’s attitude and dedication while ignoring distractions when approaching one’s art practice. In exploring natural space and dealing with reality, Cai Lei’s artworks experiment with compressing space through perspective and optical illusion, transforming the coarse reality of the living spectacle into highly distilled and stylized forms.

Exhibition View of “Cai Lei: Metonymic Liminality”

Exhibition View of “Cai Lei: Metonymic Liminality”

“Up to the pavilion and remove the ladder” is a classic allusion to the history of traditional Chinese painting. It is recorded in Xie He’s Index for Appreciating Traditional Paintings and Zhang Yanyuan’s Records of Famous Paintings of All Dynasties. It is said that Gu Junzhi, a painter from the Southern Dynasties period (420-589 CE), built a high pavilion as his studio. To prevent any distractions, he would remove the ladder whenever he comes to paint, thus people rarely get to see him.

Cai Lei, Unfinished Home 20211025, Cement, steel structure, 120x92x30cm, Base: 80x92x30cm, 2021 Cai Lei, Unfinished Home 20211112, Cement 25x22x8cm, 2021

Cai Lei, Unfinished Home 20211112, Cement 25x22x8cm, 2021

Cai Lei’s earliest known works, the Unfinished Home series, utilized architectural cement and enhanced the perspective and straight-line division to create a unique formal tension and visual experience. At the same time, the works came from the artist’s personal reality. Square Meters and Frames series developed a three-dimensional optical illusion out of a plain surface. For this, the artist adopted more explicit materials. Taking tiles and door frames as ready-made objects which serve as both the medium and the basic linguistics for a formal construct. While Cai Lei blurs the boundaries between two and three-dimensional spaces, he also blurs the boundaries between painting, sculpture, and installation. The series of acrylic paintings on canvas, Molding, extends the same creative method but further translates the exploration of artistic language directly onto canvas.

Exhibition View of “Cai Lei: Metonymic Liminality”

Exhibition View of “Cai Lei: Metonymic Liminality”

In Leftovers created in 2016, Cai Lei constructed a dense columnar concrete skyscraper, which is crude and mimetic to an almost suffocating extent to the modern urban landscape. It seemed to mark an apparent turn in Cai Lei’s creative thinking. If the previous series, Unfinished Home, Square Meters, and Frames, extract ideas from the microscopic perspective of an individual’s state of existence and life then in Leftovers, the artist’s vision and thinking adopted a universal dimension, reflecting and projecting the cold reality of self-imposed imprisonment faced by people amid rapid urbanization.

Cai Lei, Block 20211021, Bronze, 24k gold leaf, 243x56x46cm, Base: 18x132x101cm, 2021 Cai Lei, Block 20211022, Bronze, 229x69x6cm, 2021

Cai Lei, Block 20211022, Bronze, 229x69x6cm, 2021

Cai Lei’s new works produced during the epidemic outbreak, the Staircase series, alludes to the semantic meaning of “isolation”, referring to in the metonymic symbolism to “up to the pavilion and remove the ladder”. A building, a unit, a flight of stairs, the isolated unit, and the transverse staircase together constitute the conditions for isolation, control or closure. Through his work Block, Cai Lei contemplates an important dilemma: Whether it is the extraordinary circumstances of the current pandemic, or the post-isolation periods to come, an unchanging truth is the profound and complex post-globalization reality which everyone inevitably faces. At this crossroad of isolation and mobility, closure and openness, it is unclear if the future of humankind will steer towards singularity or plurality.

These three exhibitions will remain on view till January 16, 2022.

Courtesy of the Artists and Song Art Museum, edited by CAFA ART INFO.