Being one of the first generation of art historians and artists since the founding of People’s Republic of China, Prof. Shao Dazhen had a profound influence on the construction and development of Chinese fine art. He has been engaged in the research of Western art history and Chinese modern art history for a long time and has made outstanding achievements. Meanwhile, he is also an art creator who has been engaged in calligraphy and ink painting for decades. At the end of 2021, NAMOC Invitational Academic Exhibition Series “Charm of Ink in My Heart: Shao Dazhen Art Exhibition” was held at the National Art Museum of China. The exhibition showcased Shao Dazhen’s research achievements in Chinese art history, as well as over 100 unique Chinese paintings and calligraphy works which comprehensively reviewed Prof. Shao Dazhen’s artistic life which is full of literati heart and ink rhythm.

Exhibition View of “Charm of Ink in My Heart: Shao Dazhen Art Exhibition”

In the 1950s, the unique historical phenomenon of “studying in the Soviet Union” carried the ideals and pursuit of culture by a generation of predecessors. “Charm of Ink in My Heart: Shao Dazhen Art Exhibition” was not only a review of his artistic life, but it can also be taken as a microcosm of a generation of artists and an era since the founding of People’s Republic of China. Before the opening of the exhibition, CAFA ART INFO interviewed Prof. Shao. Starting from the exhibition, Prof. Shao has detailed and vividly reviewed for us his natural love of art and the generation of his creative concepts, the past events that happened during his stay in Soviet Union and his fondness for Chinese freehand tradition. After he returned to China, he introduced the motivation and process of Western modern art, as well as his judgment and insistence on the happenings in contemporary art.

Interview Date: November 23, 2021

Interview Venue: Prof. Shao Dazhen’s studio

Interviewer: Zhu Li

Editor: Mengxi

Ed. and trans. by Sue

I. Freehand Is to Portray the Heart

Zhu Li: “Charm of Ink in My Heart: Shao Dazhen Art Exhibition” was held at the National Art Museum of China on a large scale, and there were over 120 calligraphy and painting works on display. As a scholar of Chinese art history, words are the tool you can control at will. What makes us curious is why you started to create art after retirement? Where did it originate from?

Shao Dazhen: I have always liked to draw and write calligraphy, but I have never had the opportunity to develop individual creations. During my study at the Repin Academy of Fine Arts in Leningrad, Soviet Union, I studied oil painting and watercolor, mainly within the category of Western painting. Learning calligraphy started from the first grade of primary school. My enlightenment teacher was called Yang Shouzhi. He would urge us to practice calligraphy every day at six o’clock in the morning. In fact, I only learned a little Yan Zhenqing style of calligraphy and Liu Gongquan style of calligraphy. I have always been interested in calligraphy. After retiring, I wrote almost every day, and I also started to draw and gradually I began to develop some experience with writing and drawing. For the past seven or eight years, I have spent one or two hours a day writing and drawing.

Shao Dazhen, “My Enlightenment Teacher Yang Shouzhi”, 72x35cm, 2019

Shao Dazhen, “My Enlightenment Teacher Yang Shouzhi”, 72x35cm, 2019

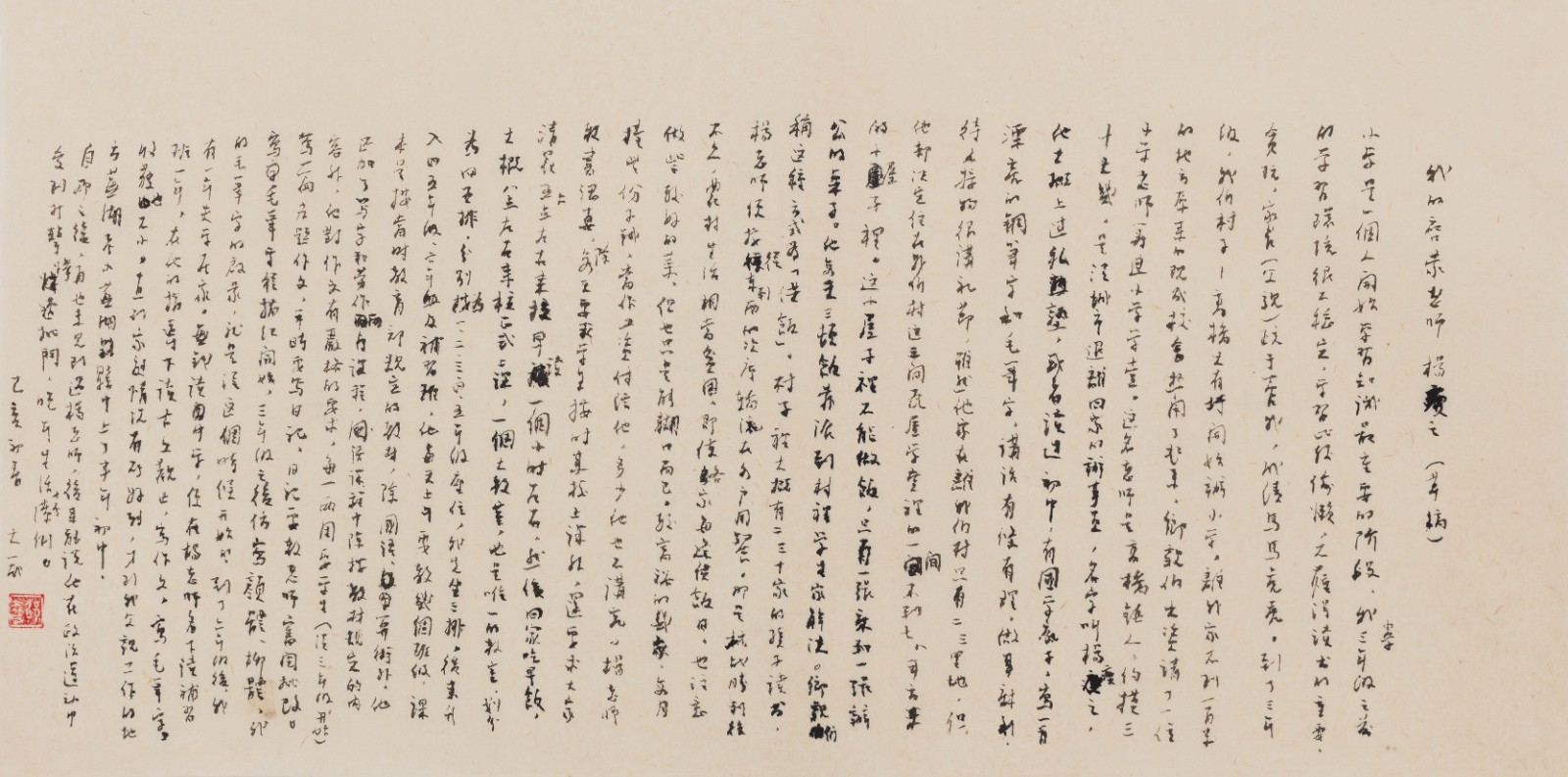

Shao Dazhen, “Me and Calligraphy”, 35cmx216cm, 2019

Shao Dazhen, “Me and Calligraphy”, 35cmx216cm, 2019

Shao Dazhen, “Thought Going with Object”, 136x34cm, 2017

Zhu Li: As you said just now, you mainly studied Western painting while studying in the Soviet Union, and you have also been studying the history of Western art. Why did you choose traditional Chinese ink painting for your individual creations?

Shao Dazhen: At the Repin Academy of Fine Arts, we had two mornings a week to learn painting, mainly watercolor, oil painting and gouache. After retiring, I insist on writing and drawing every day. Although I know that I am not good at writing and drawing, I am very interested. Perhaps because of the encouragement from Lu Chen, Zhou Sicong, Qian Shaowu, and Zhou Shaohua, my neighbor Zhou Sicong came to visit my house and said that my handwriting was like Huang Binhong’s. In fact, I never copied Huang Binhong’s calligraphy. I haven’t studied calligraphy systematically, so my calligraphy and paintings never have specific objects to copy, they all come from natural feelings. Some people say that my calligraphy is very similar to Master Hongyi. In fact, I have not studied his calligraphy. There may be a point, my characters are crooked, and I don’t pursue regularity, so it seems natural and unpretentious. I think whether it is calligraphy or painting, being natural is the most important.

Shao Dazhen, “Up and Down the Mountain”, Ink on paper, 53x54cm, 1995

Shao Dazhen, “Up and Down the Mountain”, Ink on paper, 53x54cm, 1995

Shao Dazhen, “Stable”, Ink on paper, 66x133cm, 1999

Shao Dazhen, “Stable”, Ink on paper, 66x133cm, 1999

Shao Dazhen, “Lotus Pond III”, Ink on paper, 69x69cm, 2016

Shao Dazhen, “Lotus Pond III”, Ink on paper, 69x69cm, 2016

Zhu Li: Does the pursuit of being natural have anything to do with the fact that Soviet artists and theoreticians attached great importance to the Chinese freehand tradition during your stay in the Soviet Union?

Shao Dazhen: Westerners attach great importance to the freehand tradition, and foreigners who truly understand culture appreciate the freehand tradition in Chinese calligraphy and painting. There is a Russian sentence that is difficult to translate that shows the effect of describing a “conditional, limited” creation. In the eyes of Westerners, Chinese calligraphy, painting and other artistic languages are implicit and their expressions are far from objective reality.

Zhu Li: Judging from the works in this exhibition, your creations always seem to be related to the memories of your hometown (Zhenjiang, Jiangsu province). Jiangnan (regions south of the Yangtze River) is the hometown of literati paintings. Your paintings and literati paintings seem to have something in common. The significance of Chinese literati paintings is that the starting point is not for fame and fortune, but to express subjective feelings, which is a kind of self-cultivation and spiritual sustenance. How do you think your works are related and different from literati paintings?

Shao Dazhen: I did not deliberately learn literati painting, perhaps it was from my inner character and growth experience. My family lived by the Yangtze River, about 200 meters away from the Yangtze River. Standing on the steps of my house, I can see the boats passing by on the Yangtze River. This scenery in a subtle way makes people feel the presence of a kind of painting and a little bit of poetry. Maybe my tendency to express emotions has something to do with this.

Shao Dazhen, “Lotus Pond in the Rain”, Ink on paper, 54x103cm, 2016

Shao Dazhen, “Lotus Pond in the Rain”, Ink on paper, 54x103cm, 2016

Shao Dazhen, “Both Sides of the River”, Ink on paper, 95x68cm, 2016

Shao Dazhen, “Both Sides of the River”, Ink on paper, 95x68cm, 2016

Shao Dazhen, “Free to Live and Travel”, Ink on paper, 48x79cm, 2019

Shao Dazhen, “Free to Live and Travel”, Ink on paper, 48x79cm, 2019

Zhu Li: What is particularly interesting is that you once said that you would rather paint than write an article. Can it be understood that painting has been pinned on the part of your spiritual life that is difficult to convey in words?

Shao Dazhen: Painting can be very free and is basically emotional, while writing is rational and it carries more thinking. Painting is even mysterious, it is mysterious and unpredictable, and sometimes the painter is not sure what he can draw. When I paint, I never make drafts. Huang Binhong insists that his creations have drafts, and I don’t have one either. When I draw the first stroke, I think of the second stroke, and then I think of the third stroke. The advantage is that it is natural and casual, but sometimes it is wrong, and it produces a different taste. The disadvantage is that it is not rigorous enough. Of course, the process of creation is not entirely enjoyable, there is also pain. Sometimes when I draw “there is no way out”, I just continue to draw at will, but sometimes I create new ideas, and it is easy to be cautious when making small drafts. When I write an article, I never make a draft, I don’t have an outline, I just pick up the pen and write with it. The advantage is that it is natural and not artificial. This is also similar to my life, the advantage is freedom and relaxation, and the disadvantage is the lack of rigor.

Being rational and emotional, both have their pros and cons. For some artists such as Li Keran, rationality is very important. For example, Fu Baoshi appreciates the art of drinking, and Li Keran appreciates the art of drinking tea. Fu Baoshi is casual, an art that emerges from the mind; Li Keran is thoughtful, every word and every painting is thought through.

Zhu Li: Especially for a series of your creations in 2021, it seems that the pictures are no longer important and the forms are becoming more and more abstract, especially as they show the feeling of childish writing.

Shao Dazhen: Yes, people start to have a little childlike innocence when they get old, and they don’t care anymore. In fact, I also have a lot of ideas for paintings and some ideas have not been put into practice, but I think the most important thing in painting is freedom. When you are free, you will be happy. In particular, Chinese ink and wash creations pay more attention to contingency. Ink painting is different from oil painting. Oil painting is covered layer by layer. Ink painting is very free and it is an important expression of Chinese freehand traditions and a symbol of Chinese culture.

Shao Dazhen, “A Scarce Sound”, Ink on paper, 70x137cm, 2016

Shao Dazhen, “A Scarce Sound”, Ink on paper, 70x137cm, 2016

Shao Dazhen, “Regions South and North of Yangtze River, My Home is at the South of Yangtze River”, Ink on paper, 181x97cm, 2021

Shao Dazhen, “Regions South and North of Yangtze River, My Home is at the South of Yangtze River”, Ink on paper, 181x97cm, 2021

Shao Dazhen, “Landscape, Point, Line and Surface, I Like Unfinished Body”, 81x97cm, 2021

Shao Dazhen, “Landscape, Point, Line and Surface, I Like Unfinished Body”, 81x97cm, 2021

Zhu Li: You once said that the freehand brushwork in Chinese painting is to portray the heart, and it is an expression of the mood.

Shao Dazhen: The expression of emotions is the most sublime state and it is not easy to achieve and I am also trying to achieve this.

Zhu Li: Do you sketch?

Shao Dazhen: I seldom sketch from life. Basically, I create works based on feelings, memories and imagination. Of course, the world is full of wonders, what can the mind come up with? The world is far richer than imagined, so people seem to be creating, but in fact nature and the universe have far richer things.

Zhu Li: What is the relationship among writing, research on art history and drawing in your life?

Shao Dazhen: As I said just now, writing and research are rational and creation is emotional. Research cannot rely on sensibility. Classes and articles must not be sloppy. For example, when I review artists, I must study their life very seriously, while supplemented by a lot of research, thus it can be called serious writing and research on art history, for artists at the level of perception, my exertion can be carried out, but the fundamental things must be rigorous.

Exhibition View of “Charm of Ink in My Heart: Shao Dazhen Art Exhibition” (Courtesy the National Art Museum of China)

Exhibition View of “Charm of Ink in My Heart: Shao Dazhen Art Exhibition” (Courtesy the National Art Museum of China)

II. The Years of Study in the Soviet Union and A Brief Discussion on Modern Art

Zhu Li: Just now I heard you talked about taking oil painting classes in the Soviet Union. I would like to hear about your years in the Soviet Union. How did you apply to study in the Soviet Union?

Shao Dazhen: At that time, I was a freshman in the Chinese Department of Jiangsu Normal University. The selection of students to study in the Soviet Union was actually through a recruitment examination system. Three students were selected from dozens of students in a class, and we traveled from Suzhou to Shanghai to take the examination to study in the Soviet Union. After passing the exam, we went to the preparatory department and when we were ready, we went to Beijing to study Russian for a year, and finally went to the Repin Academy of Fine Arts.

In 1958, Shao Dazhen took a group photo with his classmates who lived in the same room in the Soviet Union (Collection of Shao Dazhen)

In 1958, Shao Dazhen took a group photo with his classmates who lived in the same room in the Soviet Union (Collection of Shao Dazhen)

In 1959, Shao Dazhen took a photo in front of the statue of “Roman Youth” in the Kiev Museum, Ukraine, while collecting materials for his graduation thesis “A Textual Research on the Portrait of Roman Youth” (Collection of Shao Dazhen)

In 1959, Shao Dazhen took a photo in front of the statue of “Roman Youth” in the Kiev Museum, Ukraine, while collecting materials for his graduation thesis “A Textual Research on the Portrait of Roman Youth” (Collection of Shao Dazhen)

Zhu Li: At that time, it was the 1950s and 1960s. The Soviet Union’s literature and art also moved from a conservative state to an open and innovative state. What unforgettable experience did you have at that time, and what did inspire you to think?

Shao Dazhen: After the Soviet Union denied Stalin, it began to emancipate the mind. I remember that there were more than a dozen Soviet classmates in the Soviet dormitory and I was the only Chinese person. The students thought of opening to the outside world, and everyone was in high spirits. After Khrushchev came to power, the Soviet classmates in the dormitory were so excited that they couldn’t sleep. Their criticism of Stalin’s conservatism and autocracy had a great impact on me.

In 1956, A Conversation with Victor Michailovich Oreshnikov, Director of the Repin Academy of Fine Arts. From the left: Quan Shanshi, Shao Dazhen, Qian Shaowu, Oreshnikov, Xi Jingzhi (Collection of Quan Shanshi)

In 1956, A Conversation with Victor Michailovich Oreshnikov, Director of the Repin Academy of Fine Arts. From the left: Quan Shanshi, Shao Dazhen, Qian Shaowu, Oreshnikov, Xi Jingzhi (Collection of Quan Shanshi)

In 1958, Shao Dazhen, Xi Jingzhi, Chen Peng listened in the class (Collection of Shao Dazhen)

In 1958, Shao Dazhen, Xi Jingzhi, Chen Peng listened in the class (Collection of Shao Dazhen)

Zhu Li: After you returned from studying in the Soviet Union, you started to write A Brief Discussion on Modern Art. You can be said to be one of the first group of theorists who introduced Western modern art to China. Was the book relevant to what you saw and thought about the Soviet Union at that time?

Shao Dazhen: Yes, during the Cultural Revolution in China, everyone read Selected Works of Mao Tse-tung every day. After the Lin Biao incident, the atmosphere became a little freer. I put a book in Russian and a book in English under Selected Works of Mao Tse-tung. There was an English book called Modern Art History, an English edition with Reed’s annotations. I read Selected Works of Mao Tse-tung on the appearance and surreptitiously read Modern Art History. By the time I can write artists, it was after the reform and opening up and I began to write “modernism.” Ma Yangfeng, daughter of Ma Yinchu, President of Peking University, from Shanghai People’s Fine Arts Publishing House, gave Liu Pingjun the English version of Modern Art History for translation. I also read it and I wrote A Brief Discussion on Modern Art with it and Russian essays.

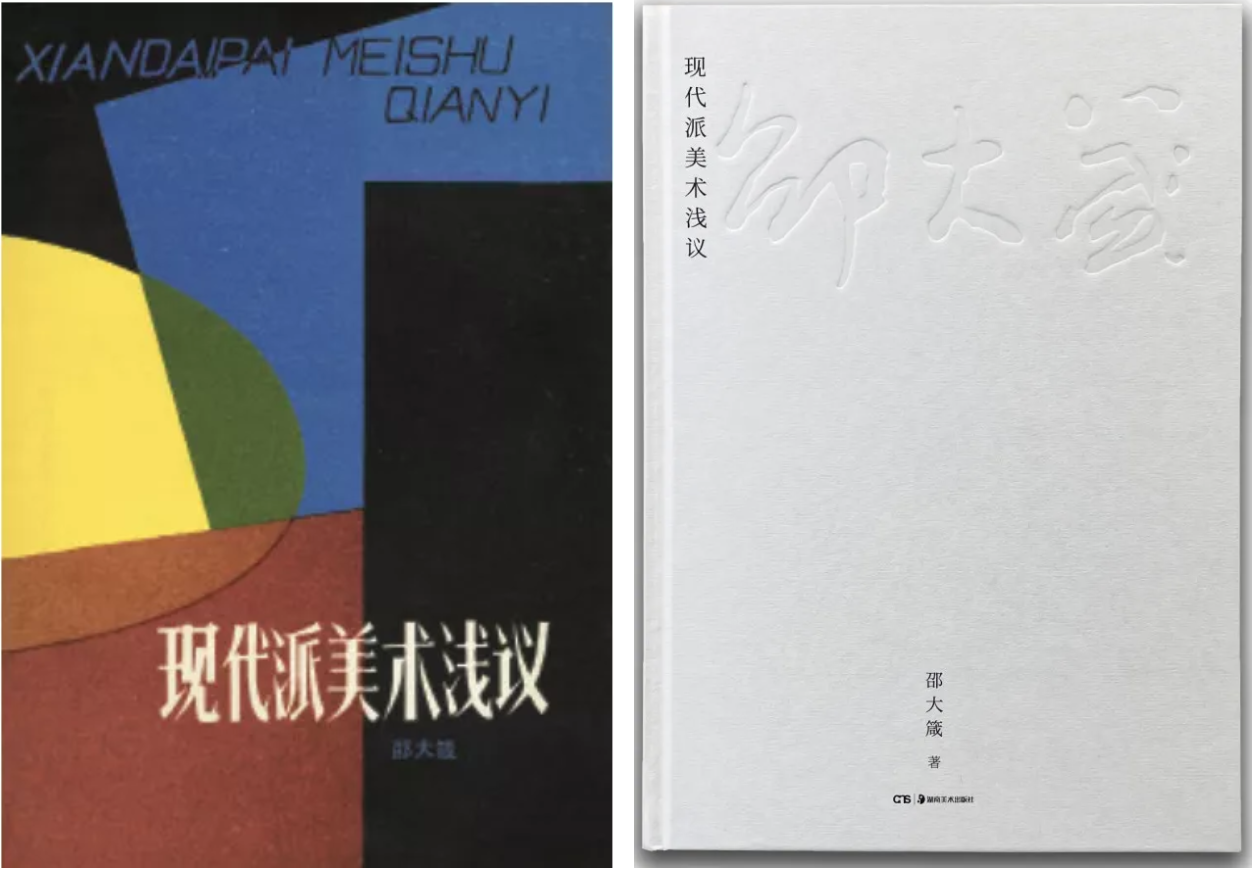

Left: Shao Dazhen, A Brief Discussion on Modern Art, 1982, Hebei Fine Arts Publishing House Right: Shao Dazhen, A Brief Discussion on Modern Art, 2021, Hunan Fine Arts Publishing House

Left: Shao Dazhen, A Brief Discussion on Modern Art, 1982, Hebei Fine Arts Publishing House Right: Shao Dazhen, A Brief Discussion on Modern Art, 2021, Hunan Fine Arts Publishing House

Zhu Li: What were your thoughts and considerations when you translated and introduced Western art at that time? What difficulties did you face?

Shao Dazhen: I was collecting materials for modern art when I was in the Soviet Union. At that time, there were a lot of art materials on the Soviet modernists. I have seen many paintings of the early modernists in the Eastern European Museum and the Pushkin Museum. At that time, the Central Academy of Fine Arts, Beijing Film Academy and the Central Academy of Drama were all called Central May Seventh University. I remember that I wrote an article at that time, using the modern formalism genre as material and also including the criticism of the formalism and it was printed out for everyone’s reference. In fact, I was very happy, because people couldn’t write about modern art at that time and when I wrote about reviewing the modernist genre, the materials actually became widespread. This manuscript is still preserved by me and is displayed as a document in this exhibition.

In 1959, a letter from the instructor, Professor Chubova, to Shao Dazhen, instructing him on how to collect the thesis materials

Zhu Li: If you were invited to review your work on introducing Western art history and art theories and divide it into stages, what are the important stages in your opinion?

Shao Dazhen: The data collection stage, including the collecting work in the Soviet Union and the collection of materials in the library after returning to China. In 1982, the Ministry of Culture sent teachers to study abroad, and Jiang Feng recommended me. At that time, I had just returned from Eastern Europe and had not been to Western Europe, so I was sent to visit France, Germany, and Italy. I saw a lot of modern art in the Soviet Union, but the trip to Western Europe in 1982 was still an eye-opener for me. This expedition was very important, and it confirmed a lot of what I learned on paper, such as in the Pompidou Centre. The works I saw in the centre and other museums also made me understand more. When I came back, I wrote a lot of articles, the main idea was “I am the master”, I have an article called “I am the master”, I hope that the artistic creation and research must be “I am the master”, that is, it must be based on a perspective from Chinese people and it can be understood, but not blindly follow it.

III. “I am the master”

Zhu Li: Entering 1960, I would like to ask you to talk about your work in establishing the discipline of art history. After returning from the Soviet Union, you entered the Department of Art History of the Central Academy of Fine Arts to teach and participate in the construction of the discipline of the Department of Art History. However, when you were in the Soviet Union, President Jiang Feng had already started related work in 1956 and he also learned from experience in the Soviet Union, including reference to the curriculum and syllabus of the Art History Department of the Repin Academy of Fine Arts translated by you and foreign students from the Soviet Union. You have also mentioned in the interview that you have undergone various exercises and tests after returning to China, and began to play a role in teaching creation and scientific research. I would like to ask you to review and talk in detail about your work in the art history discipline after returning to China.

Shao Dazhen: I went with three classmates from the Department of Art History to study in Russia. One was Cheng Yongjiang, the son of Cheng Yanqiu, who was one grade above me. The other was Li Dechun, who was enrolled in the Department of History at Lomonosov Moscow State University. Cheng Yongjiang and I were in the Department of Art History and the two of us gave a comprehensive introduction to the syllabus, teaching philosophy and teaching methods for CAFA. At that time, Jin Weinuo was the Head of the Department and Cheng Yongjiang was the Deputy Head of the Department. They combined the experience of the Soviet Union with China’s national conditions and used the applicable parts in our teaching.

Zhu Li: In 1978, it was the beginning of the reform and opening up. You co-founded the World Art magazine, which had a huge circulation in the 1980s and caused a lot of controversy. Do you still remember the idea of running a journal when you participated in the founding of World Art?

Exhibition View of “Charm of Ink in My Heart: Shao Dazhen Art Exhibition” (Courtesy the National Art Museum of China)

Exhibition View of “Charm of Ink in My Heart: Shao Dazhen Art Exhibition” (Courtesy the National Art Museum of China)

Shao Dazhen: World Art magazine mainly introduces foreign art, which is very clear. At that time, Cheng Yongjiang and I were in charge. Later, Cheng Yongjiang went to Hong Kong, so I was mainly in charge of the related affairs of the magazine. World Art introduced a lot of new art at that time, including the ancient art of the West, of course, it was mainly modern art, which was very new to the Chinese at that time. The leading personnel also included Xing Xiaosheng, who was interested in foreign art at Peking University. I transferred him to translate the articles together. There were also people in the Editorial Office who knew foreign languages. The sources of materials included foreign books and foreign journals.

Zhu Li: Returning to this exhibition, since the 1970s and 1980s, Chinese artists have been exploring the ways of Western modern art, some are complementing with the Western ways, some are sticking to tradition and some are developing a new element from traditional elements. What is your opinion on mainstream art today? Where do you think the vitality of mainstream art is pointing to?

Shao Dazhen: I think that the introduction of foreign art at the moment must “take me as the master”, to serve the current artistic prosperity and development while utilizing others’ features. Introducing the West on the one hand is to expand our cause and on the other hand is to develop our consciousness and expand our horizons.

Zhu Li: You have always held an open and pluralistic attitude towards art. The question of whether it is modern or not has not yet been clarified, and we have already begun to confront the problem of post-modernity. For example, it is the era of more popular digitalization now, and it is also the era of eliminating all values. I would like to ask you, based on your decades of observation and judgment on art as an art critic, what do you think are the fundamental values of art that we should stick to? In other words, what is the value of painting in the face of endless “incomprehensible” art in the contemporary art world?

Shao Dazhen: The development of art must pay attention to the foundation, but also to openness. The basic things cannot be “open”, the open things are to constantly update the vision, update the construction and creation. It is necessary to preserve traditions and broaden horizons, they must be combined with each other and cannot be biased towards either side. It is difficult to develop if you just keep the tradition and if you just open up to the outside world, you will lose the foundation.

Exhibition View of “Charm of Ink in My Heart: Shao Dazhen Art Exhibition” (Courtesy the National Art Museum of China)

Exhibition View of “Charm of Ink in My Heart: Shao Dazhen Art Exhibition” (Courtesy the National Art Museum of China)

Zhu Li: How do you think to make the West have a deeper understanding of Chinese artists and art theories and recognize what is good in them? Although we are constantly establishing an image of a great country, in fact, we have been using Western theories in the field of literary and art theories and our own art theory has not yet been established.

Shao Dazhen: I think it is still necessary to open up and communicate, not to be pessimistic and inferior, not to be arrogant, but to adjust the thinking concept, and not to be afraid of criticism. Criticism is very beneficial. Only by criticism can we know our own shortcomings. You should not feel attacked just because of criticism. You should take this as an opportunity to learn the advantages of others. Frankly speaking, the ideas and creations of foreigners are not necessarily more advanced than those of China, but there must be good things and advanced things and we must learn the parts where their advantages are worthy of our study. Learning from others is humility, and propaganda is self-confidence. The combination of modesty and self-confidence, neither servile nor arrogant, mastering this extent of balance is very important.

Courtesy of Shao Dazhen and the Organizer.