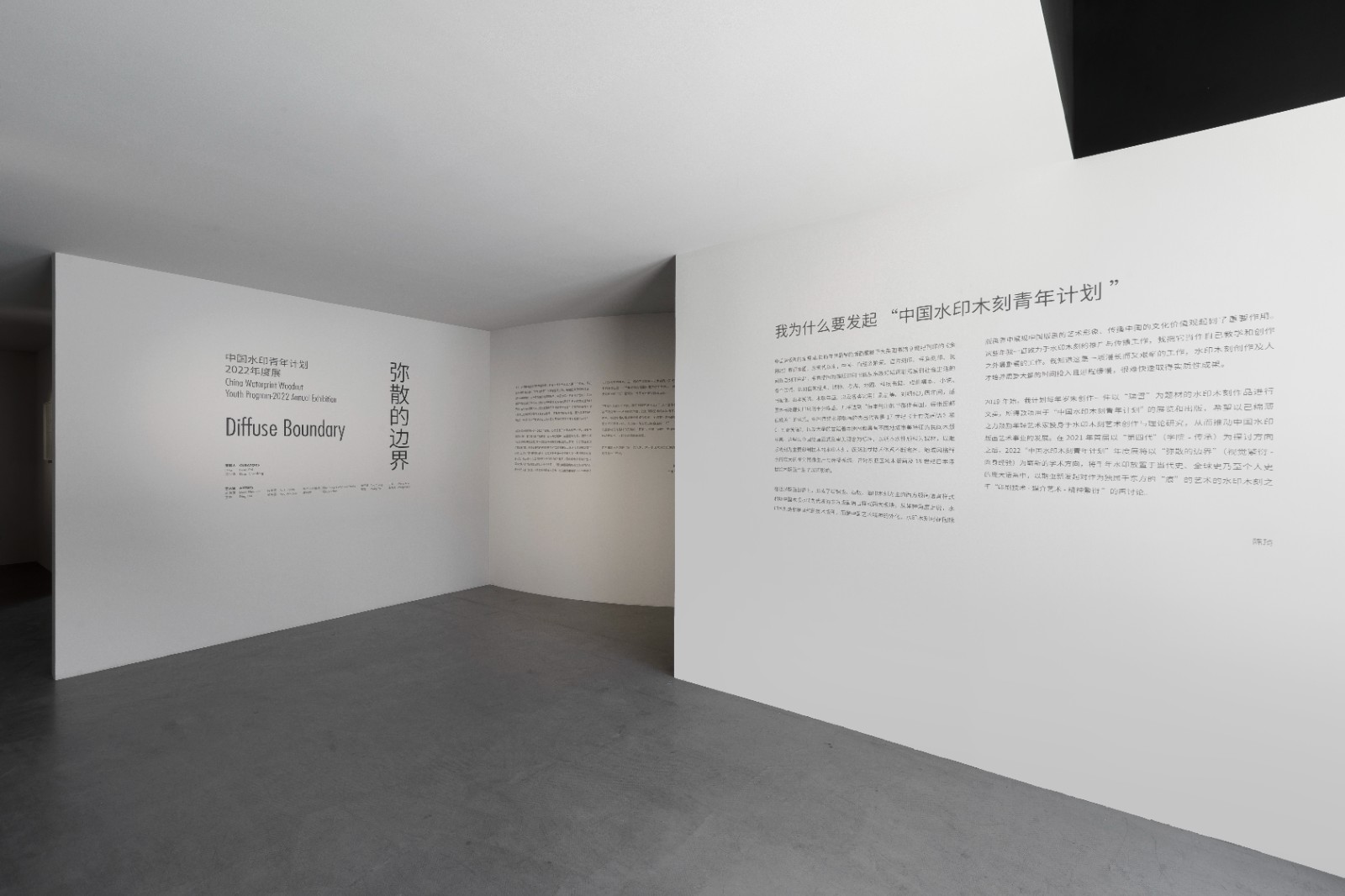

On 24th September, 2022, Asia Art Center launched “China Waterprint Woodcut Youth Program—2022 Annual Exhibition”, with Feng Shi and Duan Shaofeng as curators. This year, the exhibition is entitled “Diffuse Boundary”, focusing on the unique “Chinese visual character” and its “youth spirit” that transcends the types of printmaking. The exhibition displays more than fifty waterprint woodcut artworks by ten artists Deng Haimiao, Ding Hui, Fu Xinghan, Hou Weiguo, Han Ning & MU Print Studio, Qu Zuochun, Tao Yaqing, Wang Haidi, Wang Yan, Wang Xiao, exploring the expansive space between the history, inheritance and contemporary representation of waterprint woodcuts. [1]

Exhibition View

On the morning of 24th September, the webinar entitled “Ontology and Boundary” gathered art historians, art critics, practitioners and educators of waterprint woodcut, curators and directors of art museums, to share viewpoints under three themes of “The Imprints as Method”, “The Tradition as Media” and “The Public as Purpose”. The following texts will unfold several key factors addressed in the exhibition and the webinar to review the related events of “China Waterprint Woodcut Youth Program—2022 Annual Exhibition”.

View of “Ontology and Boundary” Webinar

View of “Ontology and Boundary” Webinar

The Purposeful Imprints and The Printmaking Mindset

Varying from the western printmaking styles such as copperplate etching, lithograph and wood engraving, the Chinese waterprint woodcut takes water-based colors as the medium and woodblock engraving as the primary printing technique. It shapes the context and spirit of Chinese tradition within the fusion of water, print and ink, which also represents the cultural image of China in the worldwide printmaking landscape.

Wang Xiao, “Narrative Poem of Water – Drift”, 2022, Waterprint Woodcut, 43x40cm

Wang Xiao, “Narrative Poem of Water – Drift”, 2022, Waterprint Woodcut, 43x40cm

Deng Haimiao, “Rhyme”, 80x68cm/98x87cm, Waterprint Woodcut, 2017

Deng Haimiao, “Rhyme”, 80x68cm/98x87cm, Waterprint Woodcut, 2017

When discussing the unique artistic value of printmaking, “imprints” have become a notion that cannot be ignored. In the webinar, the guests expanded this topic based on their respective research interests and curatorial experiences, interpreting the purposeful imprints in printmaking with multi-dimensional perspective. Meanwhile, they also addressed the significance of the printmaking mindset in not only the art creation but also in other areas of the art industry.

For example, Professor Yu Yang from CAFA mentioned that the imprint is a texture expression in between “the taste of a carving knife” and “the charm of ink brushwork”. In the temporal dimension of art history, the imprint continues its revolutionary and popular character; while in the dimension of creation methodology, it is in the game between keeping and breaking the empirical principles.

In addition to interpreting the connotation of imprints, Wu Hongliang, President of Beijing Fine Art Academy, shared his viewpoints regarding the reverse-thinking and layer-thinking of printmaking, and its plurality, indirectness, integration and long-lasting character in the creative process. The mindset of printmaking not only showcases its close relationship with traditional woodcut and printmaking creation, but also maintains an intimate and continuous relationship with contemporary art ecology.

Hou Weiguo, “No.1 Socrates and Plato No.1”, 84x138cm /105x200cm, Waterprint Woodcut, Laser Engraving, 2020

Wang Haidi, “Seek: Thank Zhongshu Book No.1”, 31x116.5cm, Waterprint Woodcut, 2018

Wang Haidi, “Seek: Thank Zhongshu Book No.1”, 31x116.5cm, Waterprint Woodcut, 2018

In a sense, the essential character of printmaking shares the high degree of similarity with digital technology and network thinking mode nowadays, which protects the pioneer spirit of printmaking from the impact of the digital era. However, it has also brought up new challenges. Today, digital art presents a trend of all-encompassing, enforcing the printmaking practitioners to consider how to retain independence of printmaking in the new era.

Plurality and Communication

Wei Xiangqi, associate research fellow at the National Art Museum of China, interpreted the notion of plurality through the examples of self-repetition and circulating time in the process of producing images by artists. Meanwhile, he also explained the controversy and dilemma in the sessions of collection, authentication and transaction due to the plural number of printmaking artworks.

Qu Zuochun, “Time Series No.5”, 92x90cm /107.7x104cm, Mimeographic Woodcut, 2019

Qu Zuochun, “Time Series No.5”, 92x90cm /107.7x104cm, Mimeographic Woodcut, 2019

If we zoom in on the field of printmaking, the plurality and communication usually cannot be separated. Professor Liu Libin from CAFA revealed in his speech that printing and printmaking, which shares focus on “plurality” and “communication”, are facing the same crisis at present. The sharp decline in the demand and quantity of paper-based printing, the rise of various new online communication methods, and the rise of single handmade book/artist books are shaking the function and meaning of printing. Regarding printmaking, the printmaking artists in the historical context are gradually replaced by illustrators in the visual part of publications. Moreover, the rise of new media and the emergence and definition of “digital printmaking” are questioning artists in terms of how to investigate, utilize and challenge the plurality that is rooted in the gene of printmaking.

In discussion regarding these two concepts, Zhang Xinying, Executive Deputy Editor-in-Chief of Chinese Printmaking focused more on the communication aspect, which is regarded as a fundamental attribute from the perspective of media, in the field of waterprint woodcut and contemporary art creation in her speech. She proposed specific artist cases to elaborate on the significance of “communication” as a two-way social interaction behavior in the breakthrough of creative language. In this diverse era lacking public standards, whether an artist can find a public symbol to carry concepts and expressions, is the key to breaking through the boundaries of media and relationships. It is also worth addressing that breaking boundaries is not the ultimate goal for artists, but clarifying a field that can be further cultivated and researched after breaking boundaries that counts.

Tao Yaqing, “Wave Climate”, 30x30cmx4, Waterprint Woodcut, 2020

Tao Yaqing, “Wave Climate”, 30x30cmx4, Waterprint Woodcut, 2020

The significance of communication today is far from only acting in the single art medium or category. With the development of public cultural spaces and exhibition contexts, the public, as the receiver of expressions, has become an indispensable part of the process of traditional reconstruction and contemporary art creation. Adhering to the comprehensive logic in concerning the whole ecology of waterprint woodcut, the organizers showcased their focus on the relationship between institutions, artistic creation and the public through the overall exhibition planning and the setting of webinar topics.

Learning from the Ancient, Transforming the Ancient and Inventing the Tradition

If we look into the specific context of waterprint woodcuts today, it faces double challenges from both inside and outside. On the one hand, within the Chinese cultural context, the waterprint woodcut is separated from its traditional history while it has absorbed the techniques and significance of western printmaking. Therefore, it is particularly urgent to extract purer national language and spiritual icons from a historical context. On the other hand, as an embodiment of national spirit and image, how should it be translated and interpreted in the global context? This is another kind of construction in the connotation of language and culture.

Ding Hui, “Face II”, 60x90cm/76x104.5cm, Waterprint Woodcut, 2006

Fu Xinghan, “Boundless Sea”, 53x76cm/76x104cm, Mixed Media on Paper, 2021

Fang Limin, Vice Dean of Fine Arts Department of China Academy of Art, discussed leaning from the ancient tradition and transforming the tradition of waterprint woodcut. The reason to learn from the ancient tradition is not only due to the profound history of Chinese traditional printmaking, but also the creative printmaking in modern China was imported from the West rather than directly developed from our tradition. If we want to pursue the uniqueness of Chinese printmaking in the global printmaking landscape, the purity of “ancient” could clearly reflect the national characteristics and be more in line with the Chinese people’s inner expression and aesthetic taste. However, it should also be clarified that the purpose to learn from the ancient tradition is to realize transformation and innovation through pursing the purer characteristics of our national roots, rather than merely becoming ancient.

Sheng Wei, Deputy Editor-in-chief of Art Magazine, also shared his opinions regarding the tradition and current state of waterprint woodcut. He proposed two cases of Peeter Baltens’ discussion in terms of the comparison between ancient art and contemporary art in 1580, and Mr. Li Hua’s reminiscence regarding the debate on the essence in the interpretation of printmaking in the Printmaking Department at CAFA at the beginning of its establishment. [2] Sheng Wei proposed that the change of media reveals the different status and roles of art in society in different times. When printmaking is incorporated into the pure art system and the academic process, the traceability of its historical legitimacy needs to be realized through “constructing tradition”.

Wang Yan, “Ten Views of Changbai Mountain-Sky Garden”, 25x37cm/27.5x39.5cm, Waterprint Woodcut, 2021

Wang Yan, “Ten Views of Changbai Mountain-Sky Garden”, 25x37cm/27.5x39.5cm, Waterprint Woodcut, 2021

Han Ning & MU Print Studio, “Twelve Chinese Zodiac Signs-Tiger”, 24.5x17.5cm/36x26cm, Waterprint Woodcut, Ink, 2015

In The Invention Of Tradition, Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger argued that despite having traceable roots, the European classical tradition as a system was actually invented and shaped in modern times, which is not continuously and naturally generated. Similarly, after 1919, a number of new words and concepts began to emerge in China, including printmaking. As Sheng Wei mentioned, when the inheritance and development of waterprint woodcut is placed in the process of the national development as one of the traditional cultural carriers to shape the national image, the discussion is undoubtedly logical in the domestic context. However, it is also necessary to confront the challenges in terms of translations, semantics and cultural connotations when it circulates in the context of international communication. For instance, how does the translation of this term highlight the unique value of “water” as a medium in the tradition and culture of Chinese printmaking? In this case, it is still challenging for theorists to research tradition, understand tradition, write about tradition and even invent tradition and define new concepts.

In the discussion of this group of keywords, Fang Limin, a printmaking practitioner and educator, and Sheng Wei, a theoretical critic, put forward their understanding of tradition from their respective perspectives, and unconsciously formed a dialogue and mutually complemented each other. When faced with specific cases of the contemporary inheritance and development of waterprint woodcuts, the two proposed different challenges faced by artists, educators and theorists and threw light on the direction they should strive for.

Exhibition View

In the exhibition, it can be observed that, on the one hand, young artists deeply researched and practiced on the form, language and aesthetics of waterprint woodcut in the historical dimension, presenting their pursuit of the spirit regarding the time and space behind the oriental philosophy. On the other hand, young artists also show their fascination with the subtle techniques of waterprint woodcut. Through the experience and improvement of techniques in their creations, they have purified their physical experience and spiritual beliefs, and integrated them into a “personal narrative” through unique “imprints”.

However, it cannot be denied that young artists need to be further perfect their artistic language and ideology. Although the exhibition is entitled “Diffuse Boundary”, expecting to enrich the creative form and cultural connotation of waterprint woodcut, most of the participating works still focus on paper-based creations in terms of formal language. What constitutes a boundary? How to realize a breakthrough? Perhaps, the development of waterprint woodcuts may not be discussed merely in the framework of one medium or one art category. This could critically enlighten young artists and even the broad waterprint woodcut ecology.

Text by Emily Weimeng Zhou and edited by Sue.

Courtesy of the organizer.

Notes:

[1] In this article, the notion waterprint woodcuts, normally known as woodblock printing (CN. 水印木刻) in an international context, refers to the translation proposed by Professor Chen Qi from the Central Academy of Fine Arts in his book “The Conception and Techniques of Chinese Waterprint Woodcut” published in 2019, and Chinese Waterprint Woodcut Archives (https://i.cafa.edu.cn/waterprint/).

[2] The focus of dispute was whether the printmaking should reveal the meaning of “woodcut” or the meaning of “publishing” within the context of the Printmaking Department at CAFA. Source from Sheng Wei’s slides.