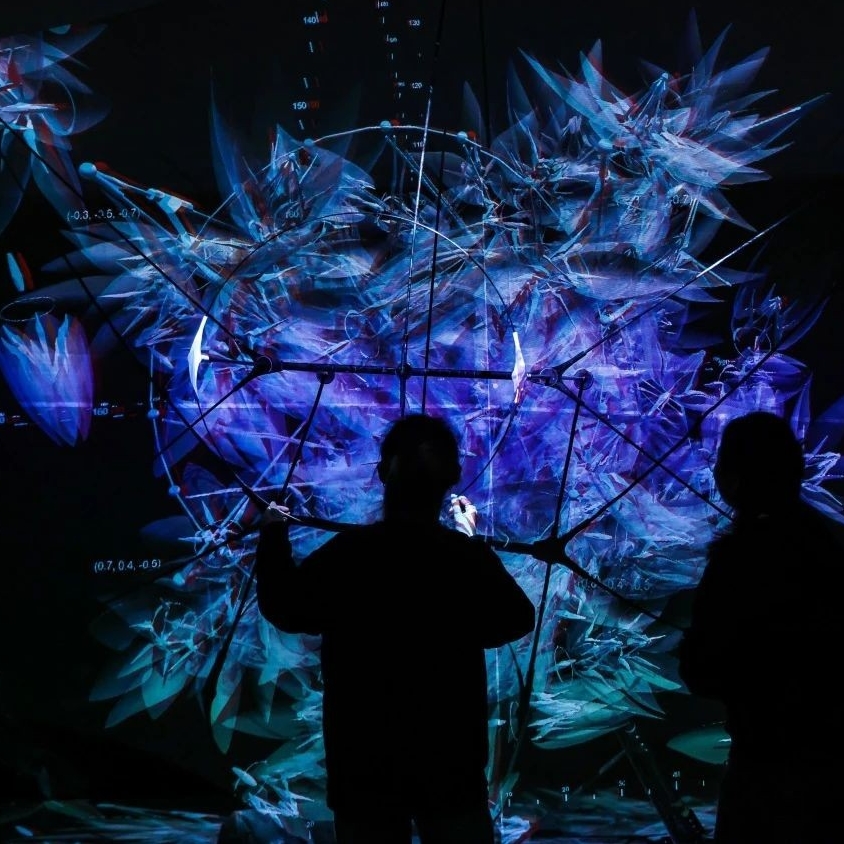

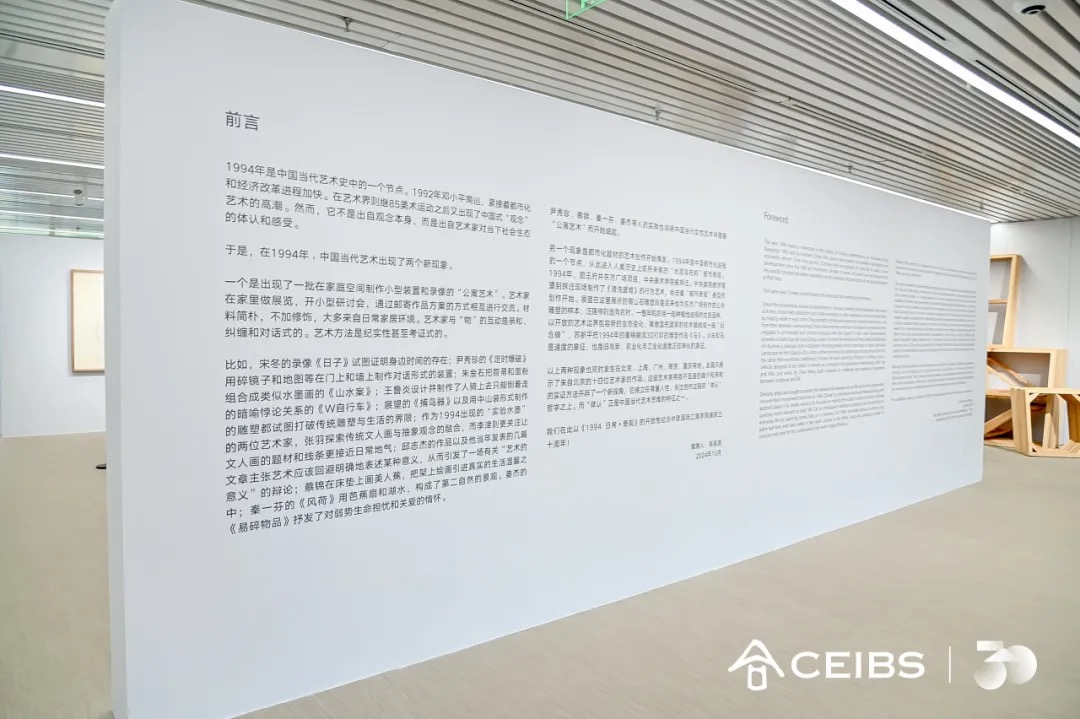

Exhibition View

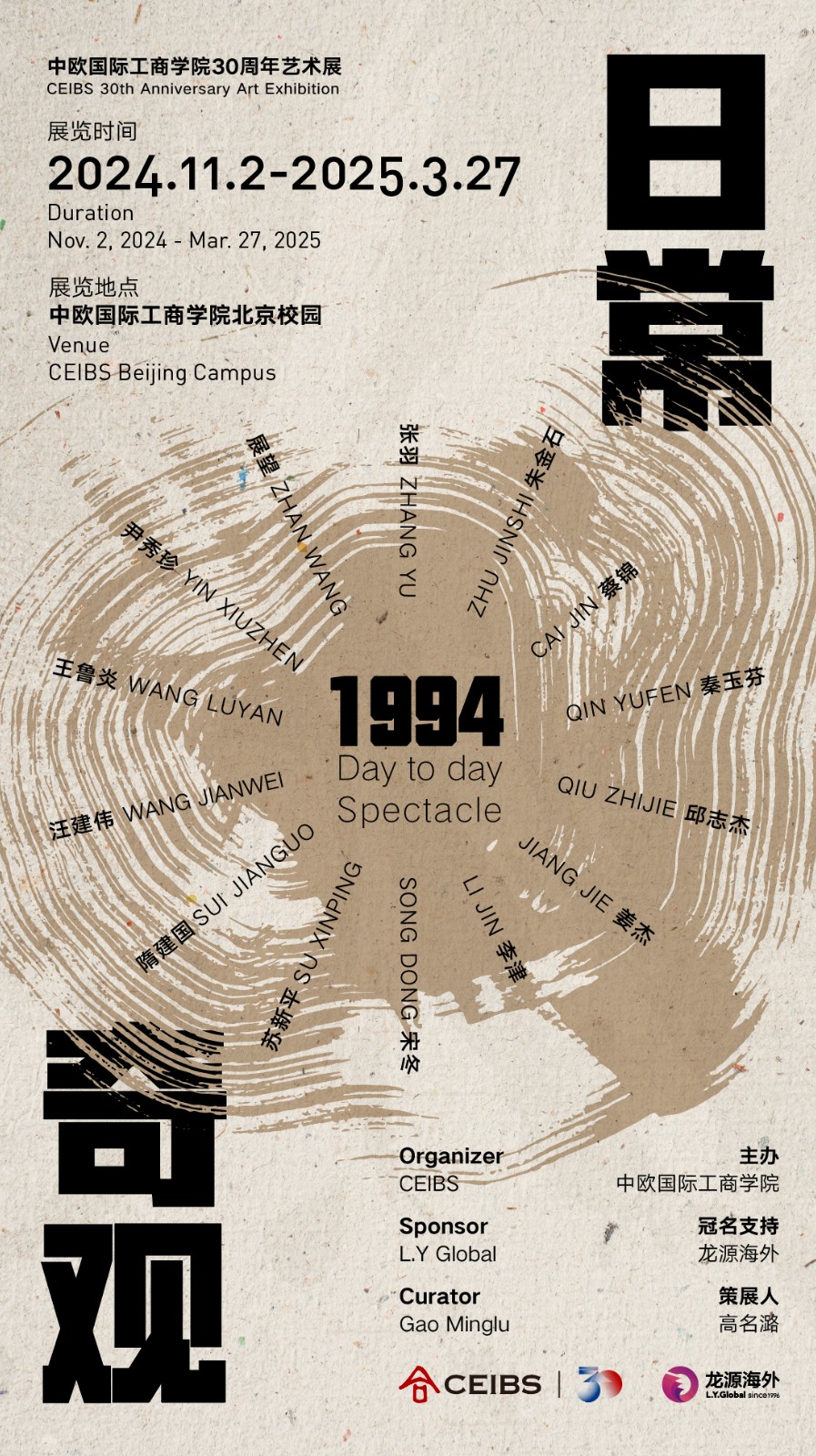

Curated by Gao Minglu, “1994: Ordinaries/Spectacles” was unveiled at the campus of CEIBS in Beijing on 2 November, 2024. The exhibition focuses on the year of “1994”, for it was not only in 1994 when CEIBS was founded, but it also represented an important node in the history of contemporary Chinese art. Starting from the phenomena of “ordinaries in apartment” and “urban spectacles” stemmed from contemporary art, the exhibition showcases the artworks and related documentation of 14 artists including Cai Jin, Qin Yufen, Qiu Zhijie, Jiang Jie, Li Jin, Song Dong, Su Xinping, Sui Jianguo, Wang Jianwei, Wang Luyan, Yin Xiuzhen, Zhan Wang, Zhang Yu and Zhu Jinshi. All of these artists have devoted themselves to expressing their thinking on the great changes of the era with “insignificant” practices at that moment, so that the meanings can be returned to the vivid daily life.

Exhibition View

Exhibition View

After Deng Xiaoping’s tour of Southern China in 1992, the process of urbanization and economic reform has been accelerated, and artists who had gone abroad returned to China one after another, therefore the art atmosphere in China became active again. Artists made their works with materials that were available and held exhibitions at home. “Apartment” as an alternative art venue was not only a means of survival for the avant-garde expressions, but it also presented a daily, private and behavioral narrative method of contemporary art. “Insignificance” has become the expressive philosophy of apartment art, and daily objects have directly become the content of apartment art. Artists retreated behind the scenes, integrating their daily life with artistic behavior, allowing seemingly ordinary expressions to return to the present and remain continuous in permanence.

The Opening Ceremony

The Opening Ceremony

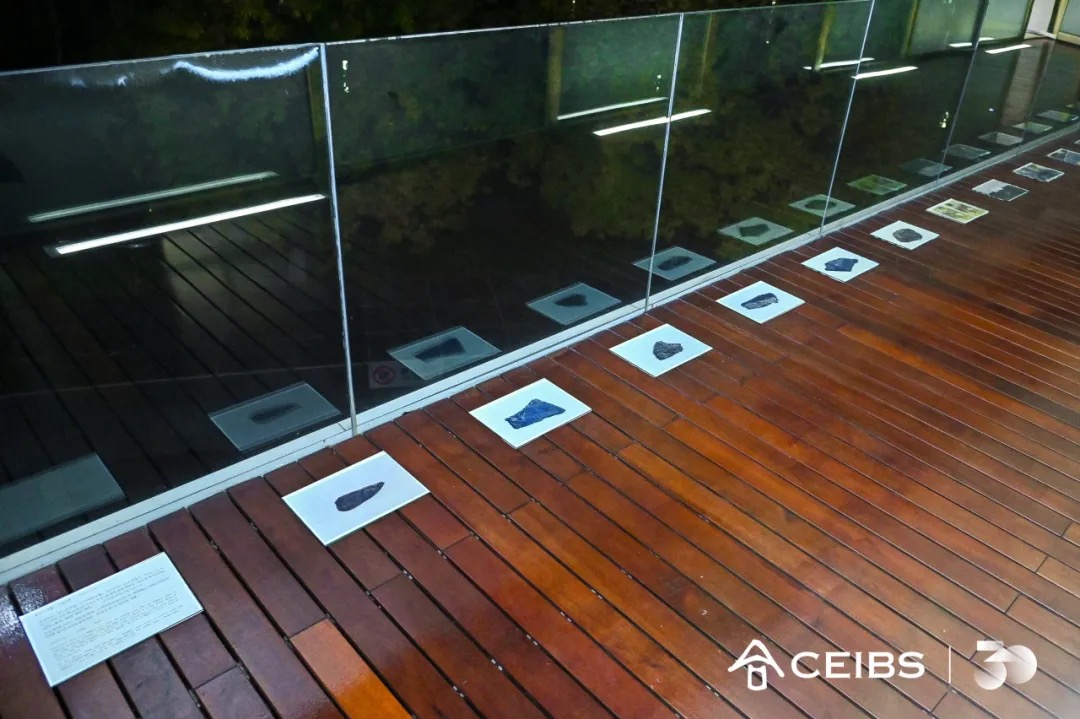

Song Dong’s video “Days” was once exhibited at the balcony of Zhu Jinshi’s apartment, for him the location was similar to the position of contemporary Chinese art, it’s dispensable while surviving in the cracks.1 Along the balcony corridor were his stones, he threw them out, recorded the location where he picked them up, and he repeated the process until he cannot find them. This self-entertaining spirit for “useless work” runs through all his artistic creations.

Song Dong, “Days” (video still), video, Dimension variable, 1994

Song Dong, “Days” (video still), video, Dimension variable, 1994 Song Dong, “Throwing Stones”, Performance, 1994-2006

Song Dong, “Throwing Stones”, Performance, 1994-2006

Ganjiakou 303 was not only a major stronghold of apartment art at that time, but it also marks the starting point of Zhu Jinshi’s art creations. With “Landscape Desk”, Zhu Jinshi conducted his art practice and thinking through “emotion of objects.”

Zhu Jinshi, “Ward”, bed, syringe, box, cement pool, turtle, dimensions variable, 1994, Ganjiakou, Beijing

Zhu Jinshi, “Ward”, bed, syringe, box, cement pool, turtle, dimensions variable, 1994, Ganjiakou, Beijing Zhu Jinshi, “Landscape Desk”, bamboo, flour, table, dimensions variable, 1995, Ganjiakou, Beijing

Zhu Jinshi, “Landscape Desk”, bamboo, flour, table, dimensions variable, 1995, Ganjiakou, Beijing

Unlike Western female artists who like to use radical materials and forms of expression, Chinese female artists tend to focus on traditional needlework materials related to home and objects. It does not mean that they identify themselves with traditional female identities, but rather choose needlework, a material that carries female methods and individual experiences, as a female “story” that is different from male art. This choice is also related to the pragmatic economic environment and the artistic atmosphere that respects artistic possibilities in the 1990s.

Yin Xiuzhen, “Relationship”, Door, plaster, cotton thread

Yin Xiuzhen, “Relationship”, Door, plaster, cotton thread

Yin Xiuzhen is a representative of apartment art. She conveys a “delicate” power, which is the visible temporal nature cast by the quality of actions, images and objects in the continuous interaction, showing the strength of daily life in the form of time.

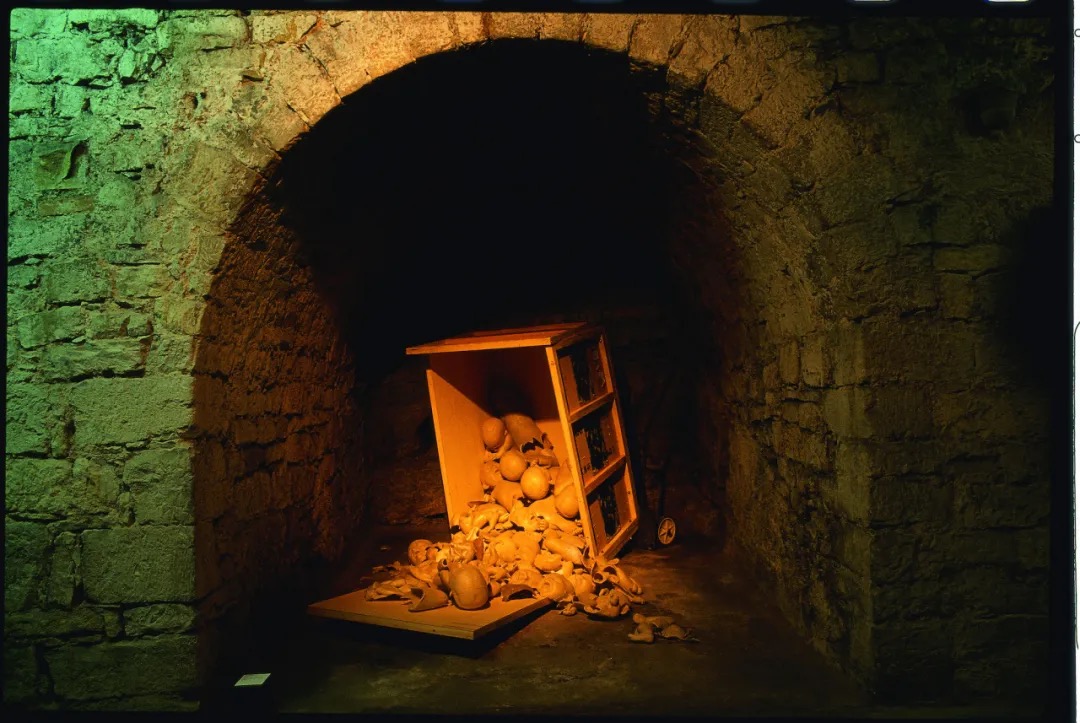

Jiang Jie, “Fragile Products”, gauze, wax, plastic film, irregular size, 1994, Installation view in Germany

Jiang Jie, “Fragile Products”, gauze, wax, plastic film, irregular size, 1994, Installation view in Germany

In “Fragile Products”, Jiang Jie made 50 baby sculptures in three different postures with wax, and then put them into a suspended plastic film at the same time, reminding the cruelty of life with collision and squeezing .

Cai Jin, “Canna 58”, 190cmx150cm, 1995

Cai Jin paints canna on mattresses, bicycle seats, women’s shoes, sofas, and so on, creating a bloody effect of red pigment mixed with ready-made products, and canna gradually evolved into a very individualistic narrative of female experience in her work. In the work “Lotus in the Wind”, Qin Yufen floated 10,000 cattail leaf fans on the surface of Kunming Lake in the Summer Palace, expanding the viewer’s perception in a gentle way like a breeze.

Qin Yufen, “Lotus in the Wind”, Ten thousand cattail leaves fans, performance installation, 1994, Kunming Lake, Summer Palace, Beijing

Qin Yufen, “Lotus in the Wind”, Ten thousand cattail leaves fans, performance installation, 1994, Kunming Lake, Summer Palace, Beijing

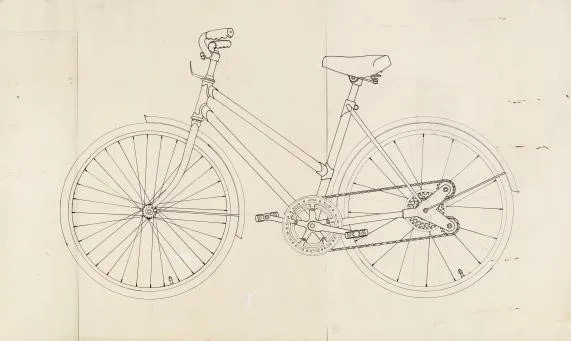

Wang Luyan analyzed the relationship between logic and anti-logic, experience and anti-experience in “W Bicycle”. The mechanical function of the bicycle he modified caused the audience to ride backwards when he intended to ride forward, which emphasized that confusion arises from judgment, because judgment arises from confusion.

Wang Luyan, “W Bicycle”, Bicycle Installation, 1996

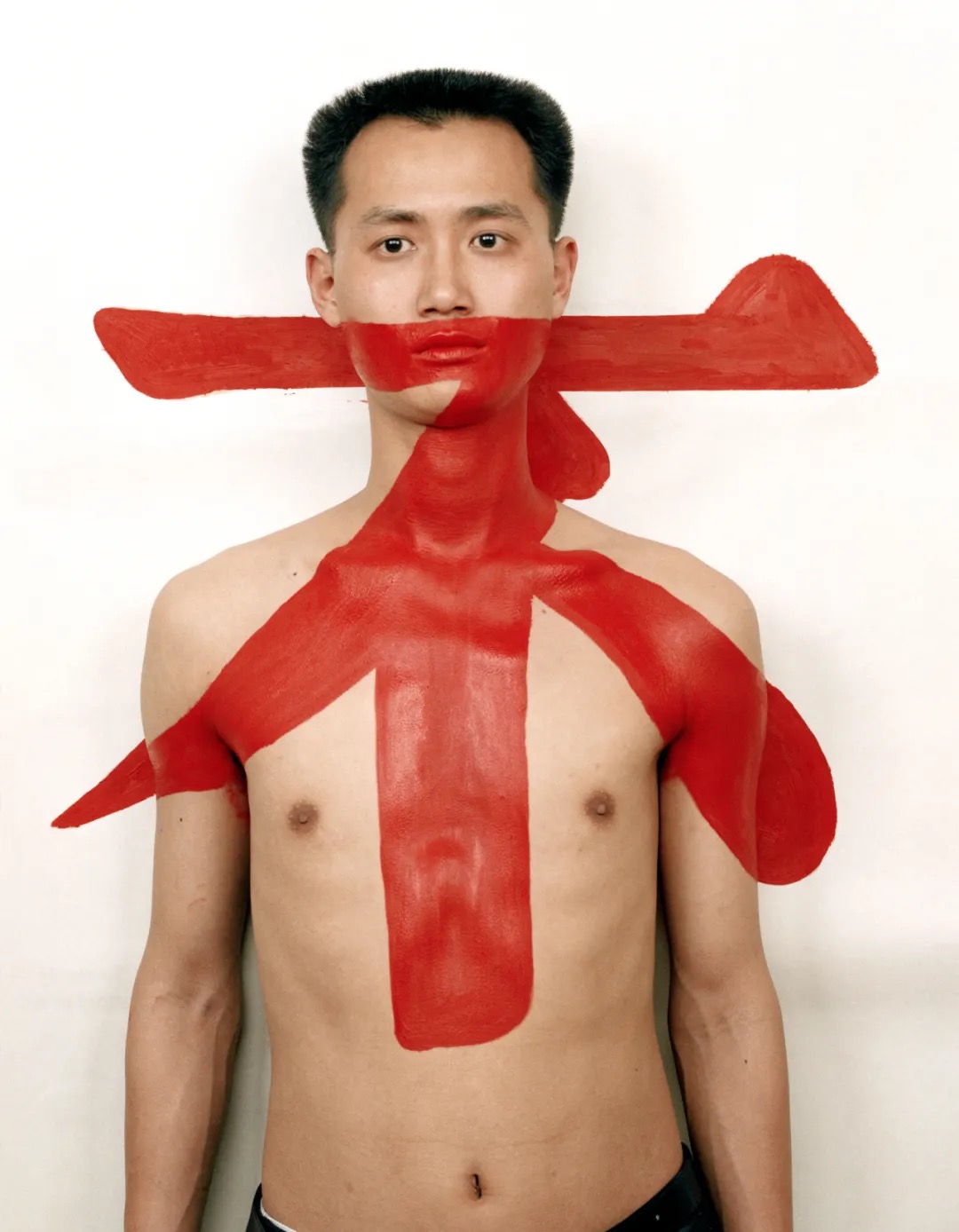

Qiu Zhijie’s “Tattoo” series discusses the relationship between an image and its background. However, he used paint and decorations to embed the picture, eliminating the sense of distance and volume between the two, and pressing the person into a flat surface.

Qiu Zhijie, “Tattoo 2”, Photography, 1994

Qiu Zhijie, “Tattoo 2”, Photography, 1994

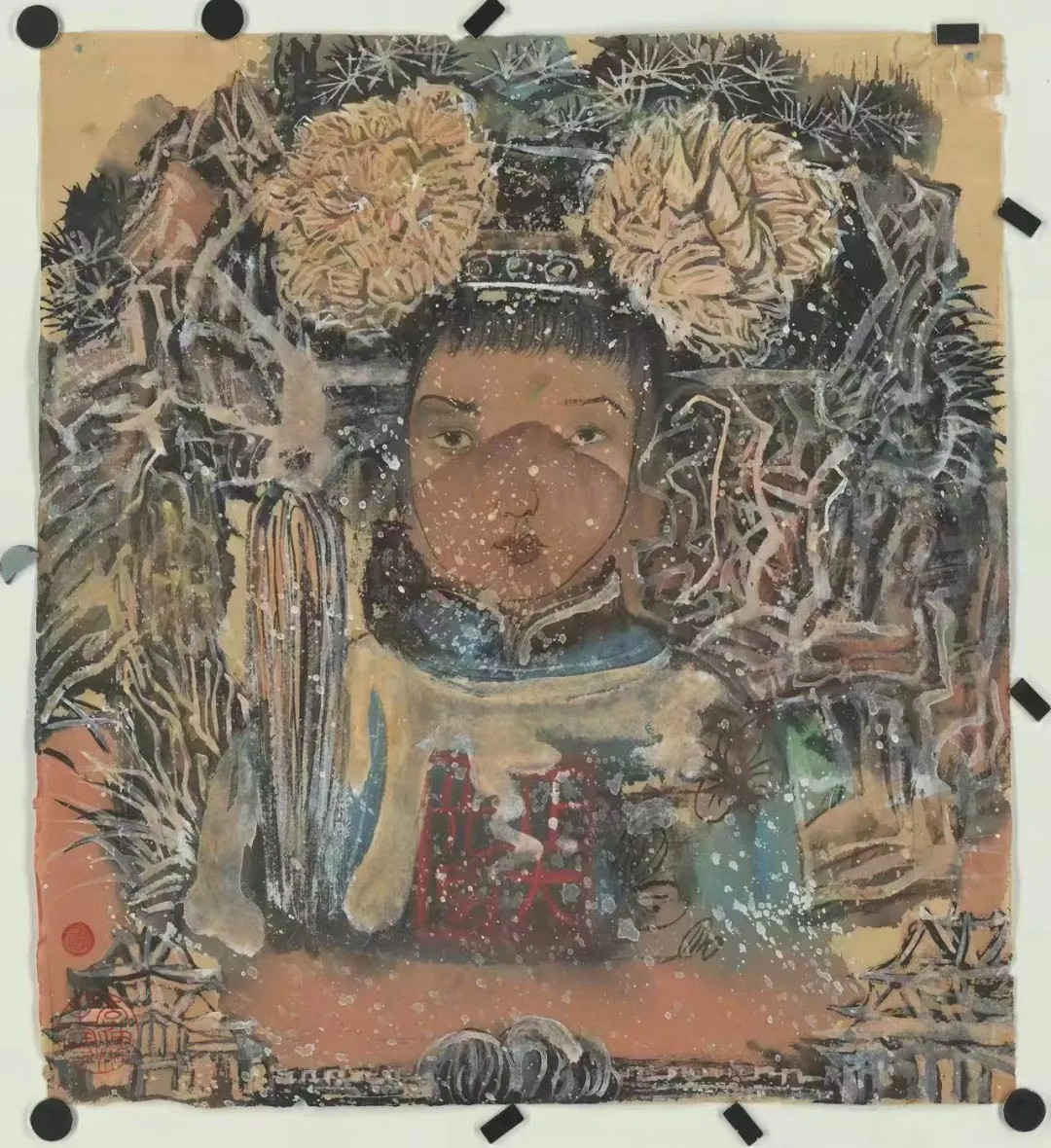

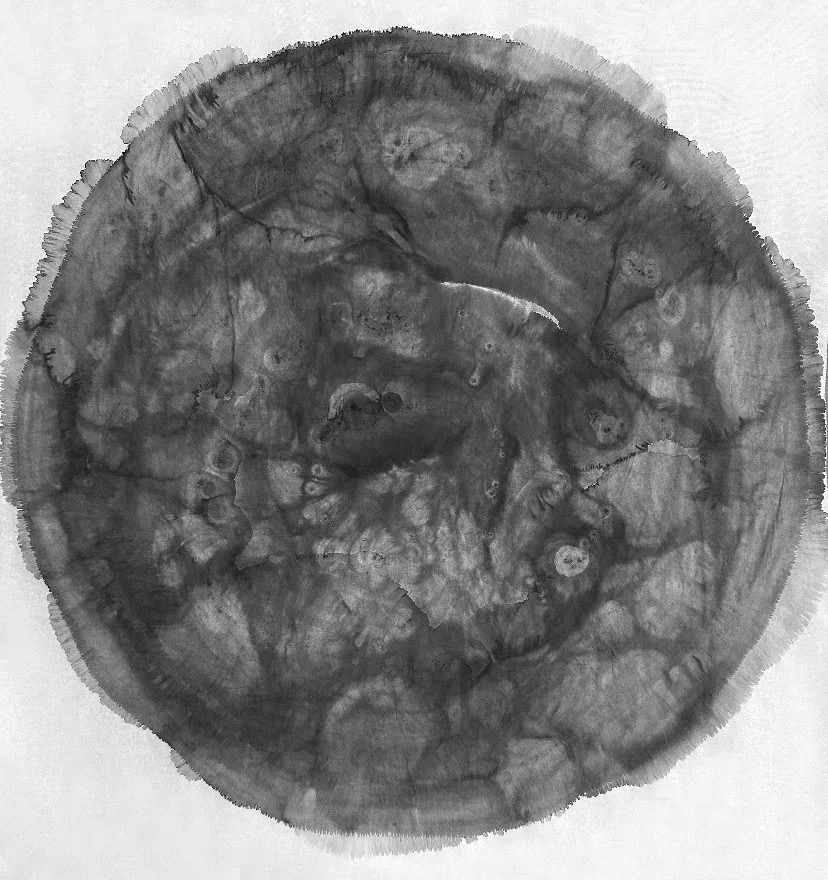

Traditional Chinese paintings were also involved in this great change. The strange combination of female body and flowers in “Beauty” by Li Jin reveals a strange and ethereal feeling and humorous intellectual ridicule. Zhang Yu’s “Qi” series of works shows his exploration from traditional literati painting to modern ink painting.

Li Jin, “Princess”, 47×42.5cm, Ink and color on paper, 1994

Li Jin, “Princess”, 47×42.5cm, Ink and color on paper, 1994 Zhang Yu, “Qi 19940217”, Rice paper, ink, shampoo, 1994

Zhang Yu, “Qi 19940217”, Rice paper, ink, shampoo, 1994

The end of the 20th century witnessed tremendous environmental changes. In contrast to apartment art, there was a surge in urban-themed artistic creation. Zhan Wang’s “94 Clean Ruins” at the demolition site marks the beginning of “Urban Spectacles”. In his exploration of sculptural expression, Zhan Wang found a new mission for his works—to become a witness to the great changes in the city.

Zhan Wang, “Clean Ruins”, 1994, Photography, 60x80cm

In “1994: Memory Space”, Sui Jianguo used abandoned railway sleepers, tied them into walls, and enclosed a space, trying in vain to wrap up invisible memories to commemorate the changes and migrations of roads brought about by rapid development.

Sui Jianguo, “1994: Memory Space”, Old Sleepers, 1994

Sui Jianguo, “1994: Memory Space”, Old Sleepers, 1994

A white horse standing outdoors with its head down is the sculpture “Horse” by artist Su Xinping, which was created by 3D printing from a drawing he made in 1994. The dramatic changes from being slow to being fast and from the old to the new brought about by urbanization and his yearning for the natural grassland are both conflicting and coexisting, reflecting the artist’s philosophical thinking on life, time and existence.

Su Xinping, “White Horse”, 211×52.5×104cm, Photosensitive resin, 2024

Su Xinping, “White Horse”, 211×52.5×104cm, Photosensitive resin, 2024

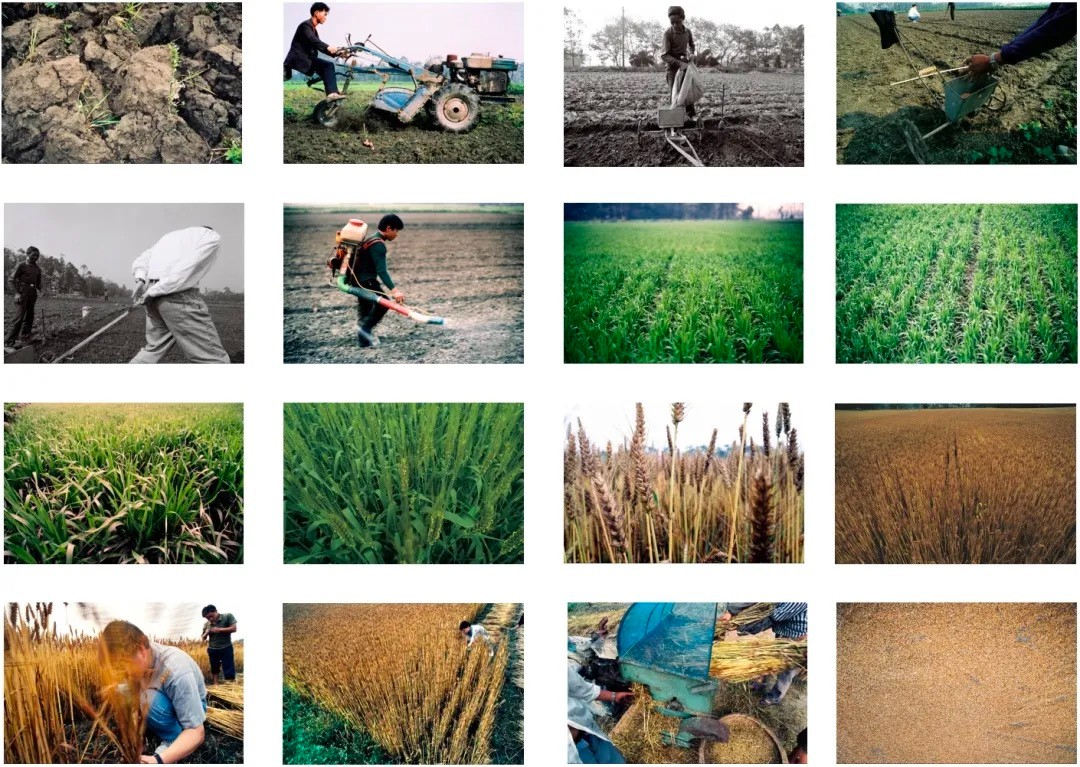

Between 1993 and 1994, Wang Jianwei went deep into nature and worked with local farmers in the countryside to record the production process of wheat from sowing to harvesting, completing the work “Planting—Cycle”. He tried to establish a de-subjectified relationship between the natural attributes of objects and their social functions, and opposed making art a tool for meaning.

Wang Jianwei, “Planting—Cycle”, Photograph, digital micro-print, 29×44cm, 16 sheets in total, 1994

Wang Jianwei, “Planting—Cycle”, Photograph, digital micro-print, 29×44cm, 16 sheets in total, 1994

Gao Minglu pointed out in History of Chinese Contemporary Art that the “ordinaries” and urban “spectacles” contained in “apartment art” were the dominant trends in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. However, “ordinaries” and “spectacles” are not opposites. On the contrary, they reflect the unique methodology of contemporary Chinese art, which is both contradictory and mutually transformative between “documentary” and “virtualization”. As artist Sui Jianguo lamented at the opening ceremony: “The trend formed in the early 1990s broke through the dam of the past. Each artist made art according to his or her own choice, like a river flowing along the ground. 30 years later, some artists have become a small river. It is no longer just a trend, but an echo of all river systems.” What will the future be like? Let us wait for the echo of time.

Text (CN) by Jinzhi, edited (EN) by Sue/CAFA ART INFO

Note:

Gao Minglu, History of Chinese Contemporary Art, Shanghai University Press, 2021.1, p336.

About the Exhibition

Curator: Gao Minglu

Dates: Nov. 2, 2024 – Mar. 27, 2025

Venue: CEIBS Beijing Campus