“I’m 57 years old now, and I’m moving forward to being middle-aged and part of the elderly team. Time will not follow my command, and it never stops to wait for me to figure out how I will spend the rest of my life. I don’t know how to live well for the rest of my life, but I know that I will experience a physical decline, cerebellum atrophy with my eyes becoming dizzy, I might repeat words without knowing it, become hesitant and suspicious of things, pretending to be decisive but communicating that something more wrong, feeling depressed and unhappy. Therefore I want to draw some old friends, some older than me, some younger than me, and I still don’t know what they think, whether they think the rest of their lives will be better.”

—Liu Xiaodong on 3 October, 2020

Portraiture is the unfading temptation of plastic arts. At the opening of the exhibition, Liu Xiaodong explained the difference between this series of portraits and his previous work, which was inspired by Ah Cheng: “Drawing more than ten people is to express oneself, and if you draw less people, it is to express others.” The criteria for these portraits is also very simple, the subjects must be friends who have been with him for more than 30 years.

What’s interesting is that these are the kith and kin of Liu Xiaodong including Ah Cheng, Zhang Yuan, Wang Xiaoshuai, Yu Hong, and others who have occupied the artist’s enthusiastic life for more than 30 years and have endowed these portraits with the attributes of public portraits. Their faces take on what Thomas Macho calls “Vorbild” in the exhibition. 1

Exhibition View of “Liu Xiaodong: Your Friends” | Courtesy UCCA Center for Contemporary Art.

Exhibition View of “Liu Xiaodong: Your Friends” | Courtesy UCCA Center for Contemporary Art.

Being similar to the recognition of Andy Warhol’s celebrity circle of friends who appeared in the UCCA Center for Contemporary Art six months ago, they (public figures) are all products of the media, “always forcibly standing in front of people” 2—their history is well known to the public and their faces are capable of jumping abruptly in front of the audience in the exhibition. Their half-real and half-fictional stories and the frozen moments in the pictures work together to weave an extended content in the audience’s mind, and they further add a layer of the temporal to the work. Their appearance is not just the carrier of friendship and emotion, but it also bears the function of the exhibition in reaching the public. At least for the cultural world, who doesn’t want to take a look at Liu Xiaodong’s painting of Ah Cheng?

Exhibition view of “Liu Xiaodong: Your Friends” | Courtesy UCCA Center for Contemporary Art

Exhibition view of “Liu Xiaodong: Your Friends” | Courtesy UCCA Center for Contemporary Art

Whiskey and Coffee/Diurnal Brazier/Green Bamboo/Red Scissors

Liu Xiaodong’s expression on the theme of being middle-aged and elderly in this exhibition stems from his personal life experience, as well as from the mutual reference between Liu Xiaodong and his old friends, “The world is full of middle-aged and elderly people and there will always be middle-aged and elderly period for everyone, but each individual enters it for the first time.” 3 Liu Xiaodong decided to record his friends who entered the middle-aged and elderly period one after another.

Compared with Ah Cheng, Big Yuan shows the extra cruelty caused by time. The significance completed in the audience’s mind is supplemented in the portrait of Zhang Yuan who is a leading director in China’s “Sixth Generation” cinema, an extraordinary chemical reaction is stimulated, and a certain existential expression stemmed from the character’s past has a negative correlation with what was presented in the picture. Portraits appeal to the fact that the artist constantly approaches the “self”, with some perfunctory deceit that language can reach totally as revealed in art. In portrait painting, the artist and the subjects are so brave in revealing themselves that it plays a decisive role. For this pioneering director who doubtlessly displayed the youth culture in the 1970s and 1980s and paid attention to the marginalized groups of society, the artist finally presented the image of a middle-aged artist loves whisky and coffee with liquor never leaves his hand.

The artist candidly captures the heartbreaking elements in the subject’s soul. Nervous, stubborn eyes, and extraordinarily slender limbs in contrast to the slightly fat stature, the former is not only unable to coordinate on the sofa, but also always seems to have nowhere to be in the picture, ready to leave at any time, the artist really let his right foot “disappear.”

Liu Xiaodong, Big Yuan, 2020, Oil on canvas, 150×140 cm. Courtesy the artist.

Liu Xiaodong, Big Yuan, 2020, Oil on canvas, 150×140 cm. Courtesy the artist.

This unfinished feeling with expressive elements, together with the realistic shaping in the picture, achieves the unity of “form and spirit” that Chinese portrait painting emphasizes: corresponding to the traces of a struggle in a person’s body in his young age, is an unfinished and abruptly stopped state—the subject in the painting is close to the carrier of transitioning from the atmosphere of a certain era to the present, so that Big Yuan has the necessary typical characteristics to become a classic work.

Liu Xiaodong, Big Yuan, 2020, Oil on canvas, 150×140 cm (detail). Courtesy the artist.

For Liu Xiaodong, body language is far more important than eyes, as it is the perennial habits that form a person’s body. It can be seen that the artist carefully shapes the “form” in order to depict the soul of the character with infinite accuracy, expressing “fierce love and timeless friendship” as well as the “unspeakable emotions.”

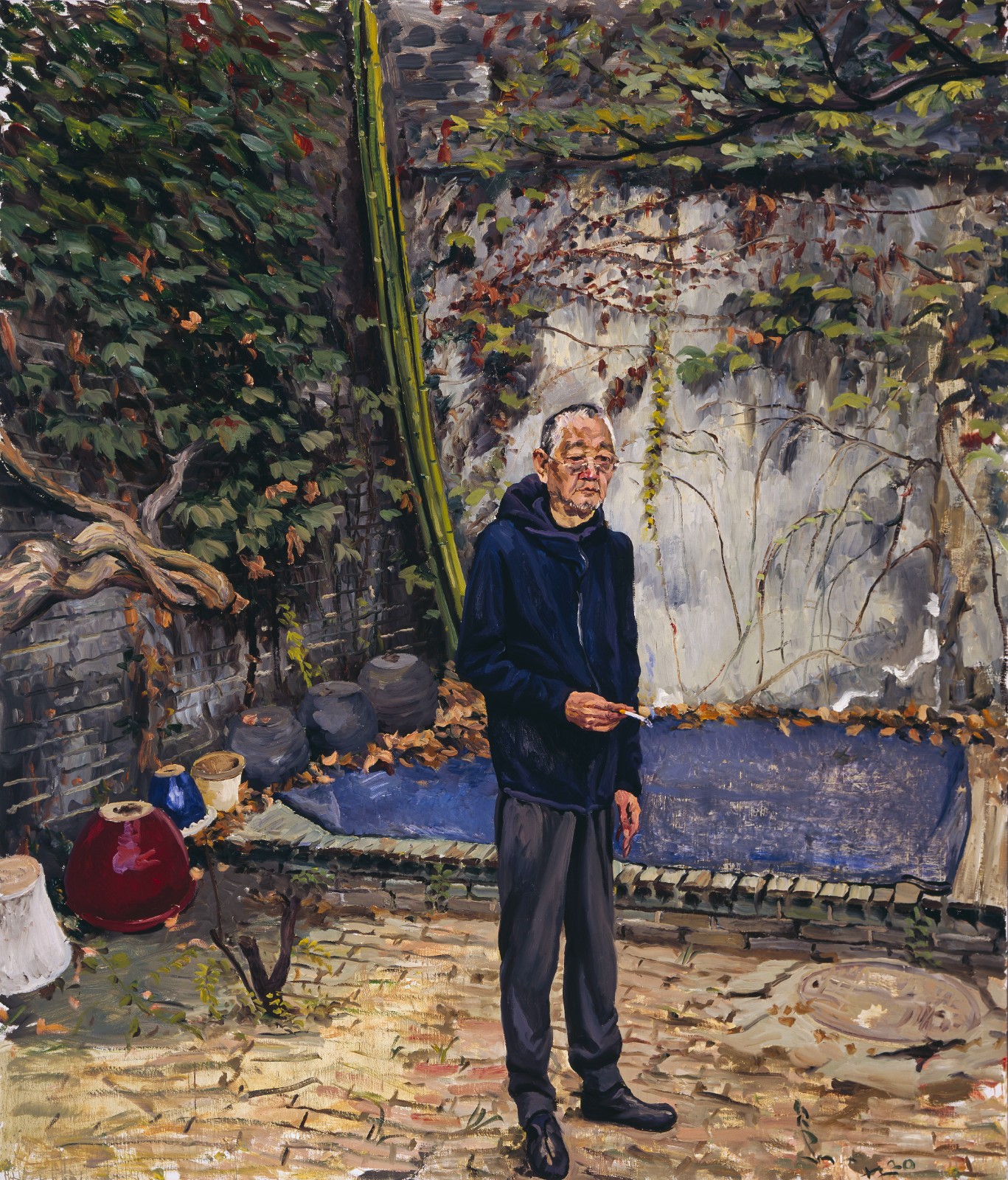

Liu Xiaodong, Ah Cheng, 2020, Oil on canvas, 270×230 cm. Courtesy the artist.

Liu Xiaodong, Ah Cheng, 2020, Oil on canvas, 270×230 cm. Courtesy the artist.

Thus Ah Cheng became the character of “Wang Yisheng” from his novel King of Chess in Liu Xiaodong’s painting, who was so thin as if he had no buttocks. “Long legs like two cigarettes poked support for the temperament of the whole Ah Cheng.” In the background, what connects Ah Cheng and extends infinitely up to the outside of the painting, is a bundle of green bamboo, and below it is a blue plastic sheet that looks like living water.

Liu Xiaodong, Yu Hong, 2020, Oil on canvas, 260×220 cm. Courtesy the artist.

Liu Xiaodong, Yu Hong, 2020, Oil on canvas, 260×220 cm. Courtesy the artist.

The protagonist of “Ferocious Love”, reminiscent of the mysterious heroine of a Hollywood film noir, has a “mini pistol” in her hand that becomes a pair of red scissors. In the diary exhibited, Liu Xiaodong wrote on how he waited for two months so that the magnolias in the studio bloomed, and he portrayed the intricate shadow swept over Yu Hong’s face. Shadows and lines form what can hardly be described as gentle and romantic shapes. In Xiaoshuai, the character in the painting is leaning on a computer chair, facing a brazier with a gloomy face. Liu Xiaodong’s interest in this painting is largely focused on the flames that continue to burn in vain during the day, and in a repeated and meticulous way he depicts the visual distortions created by the fire licking the air.

Liu Xiaodong, Xiaoshuai, 2020, Oil on canvas, 260×220 cm. Courtesy the artist.

Liu Xiaodong, Xiaoshuai, 2020, Oil on canvas, 260×220 cm. Courtesy the artist.

Liu Xiaodong, Xiaoshuai, 2020, Oil on canvas, 260×220 cm (detail). Courtesy the artist.

“The process of portraiture is actually a process of observing it, a process of re-examining the relationship with the character.” Liu Xiaodong always felt that the character became smaller after painting. In the documentary, Liu Xiaodong repeatedly emphasized on the anguish that “the closer you get to people, the harder it is to draw”. Painting a portrait is a test of connection and also an inquiry. The differences and dislocations between the painter and the painted contain a certain real dimension of the emotional relationship between people.

The representation of “self” always involves a wrestling between the painter and the person being painted. The artist’s gaze and the perplexity of the subject confronting the “self” in the painting prompted Liu Xiaodong to put the artist’s helplessness and ridicule that the artist is always pressed to change the painting into the lyrics of the last song for the documentary Your Friends—

“Make the eyes bigger

make the neck longer

belly smaller

get taller

Your city, your landscape, your friends.

Make the sky bluer

make the wall darker

make things right

Your city, your landscape, your friends.

Make the city emptier

the mountain more stable

Change the water more honestly

less changes for friends

Your city, your landscape, your friends.”

Intellectual Portraits and Popular Portraits

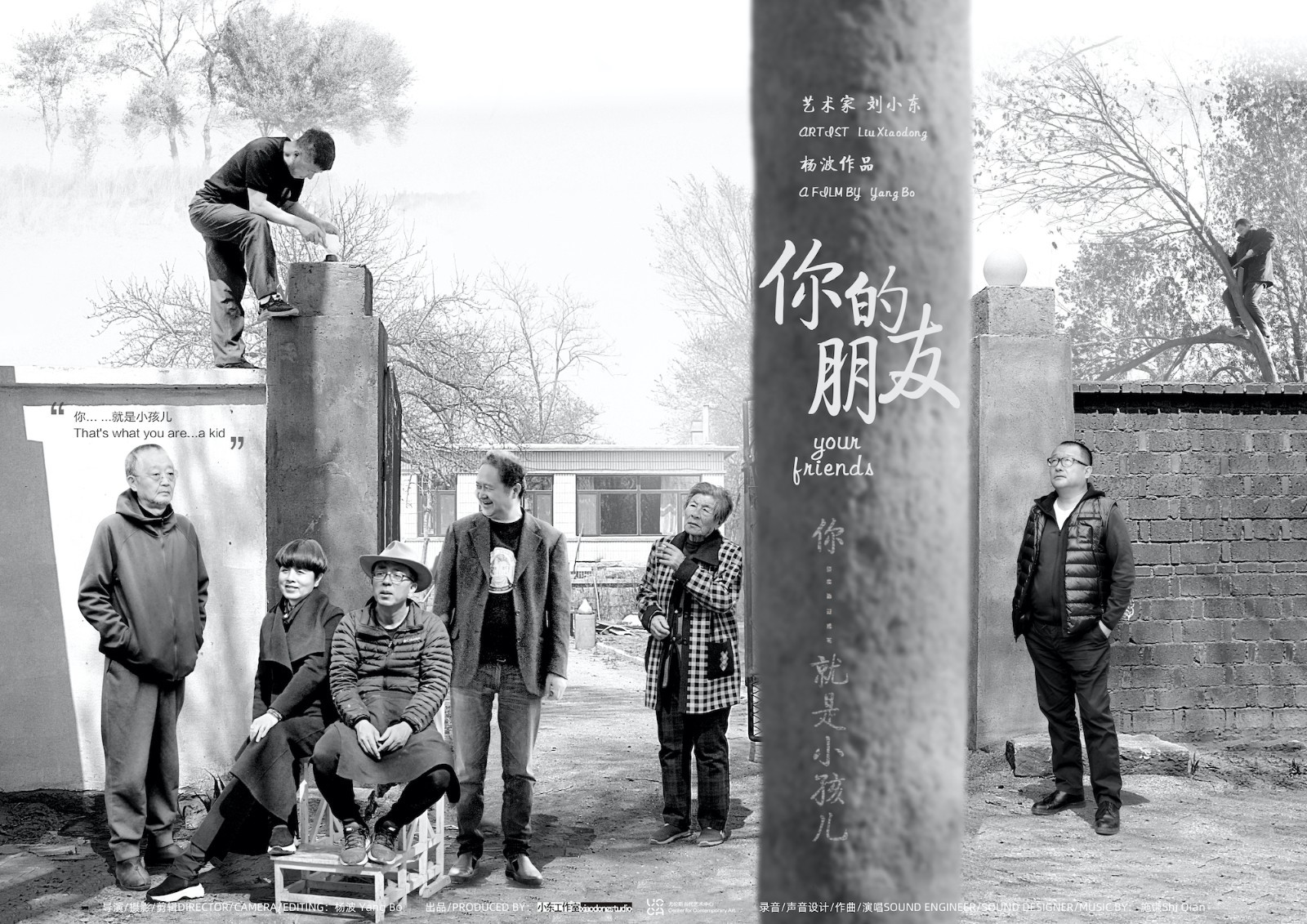

Liu Xiaodong tried to “approach” the subjects, including his radiant circle of friends and his family in Heitukeng (Black Earth Pit). At the exhibition site, the documentary directed by Yang Bo recorded the entire process that Liu Xiaodong painted for his friends, wife and relatives.

Poster of Documentary Your Friends, Courtesy Director Yang Bo.

Poster of Documentary Your Friends, Courtesy Director Yang Bo.

Exhibition View | Courtesy UCCA Center for Contemporary Art.

Exhibition View | Courtesy UCCA Center for Contemporary Art.

When the film is screened to the “Heitukeng Movement”, the audience will see how Liu Xiaodong, carries the sorrow of an intellectual, makes fun of how he has become an eye-catching and unproductive “loafer” after returning to his hometown—becoming a brain that is a little bit raw in the bowl of sorghum rice.

The “schizophrenia” caused by the urban-rural duality pattern in contemporary citizens, relying on Liu Xiaodong’s naturalistic “acting skills”, has been humorously expressed in the daily life and sketching process with his mother, brother, and childhood friends, which makes people laugh, also reminiscent of jokes flying over the Internet during the period of Chinese New Year, after Mitchell from the art museum and Andy from the media department returned to their hometowns, and they might again become “Xiaocui” and “Big Qiang.”

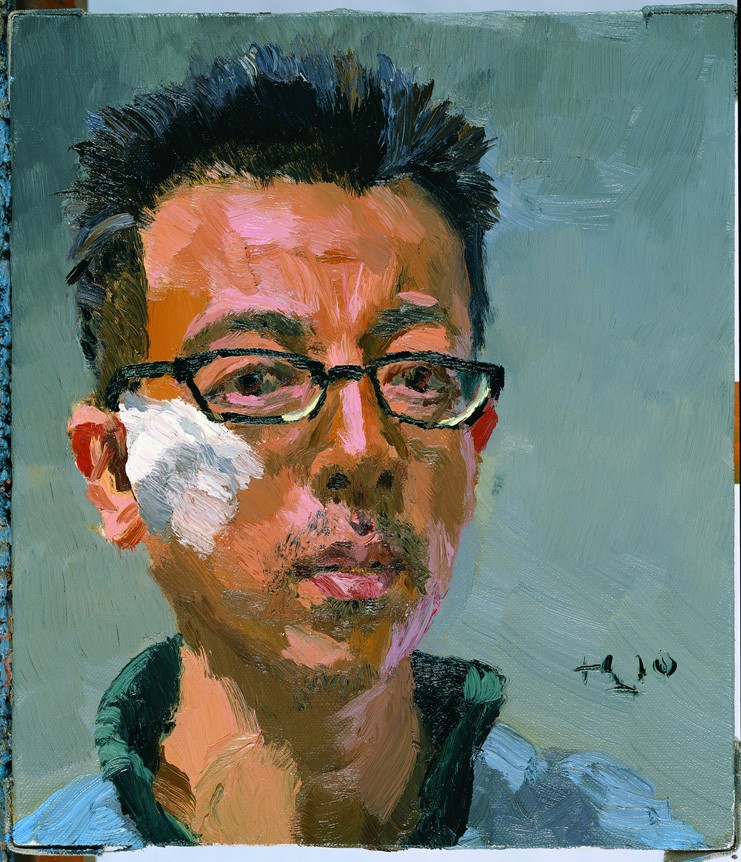

A self-portrait of Liu Xiaodong has become an intermediary between the two levels of life. In the picture, Liu Xiaodong walked naked on the land in the Northeast China. When visitors pass in front of this painting, they walk from “enthusiastic lifetime” to a scene of “Heitukeng Moment.”

Exhibition View of “Liu Xiaodong: Your Friends” | Courtesy UCCA Center for Contemporary Art.

The tension between the rustic name of Heitukeng and the foreign elevation of movement, tends to merge in the artist’s affection for his hometown and family, which also become the perspective chosen by the artist to portray his family members and villagers, as it is a “fusion” with love, nostalgia as well as fear.

Liu Xiaodong, My Mother, My Brother, and Myself, 2021, Watercolor on paper, 34×25.5 cm. Courtesy the artist.

Liu Xiaodong, My Mother, My Brother, and Myself, 2021, Watercolor on paper, 34×25.5 cm. Courtesy the artist.

Liu Xiaodong, Yang Hua Climbing a Tree, 2021, Watercolor on paper, 34×25.5 cm. Courtesy the artist.

Liu Xiaodong, Yang Hua Climbing a Tree, 2021, Watercolor on paper, 34×25.5 cm. Courtesy the artist.

The extension of the urban-rural structure forms a contrasting treatment of intellectuals and public portraits in the artist’s pictorial arrangement. Whether it’s Ah Cheng, Yu Hong, Wang Xiaoshuai, Zhang Yuan, or Ning Dai in Person Having a Laugh, which drew two generations, these characters have always been in indoor and semi-indoor scenes, and the walls and half walls constitute a sheltered scene; In contrast, his mother, brother, relatives and friends are mostly in a wider open landscape.

Liu Xiaodong, Ning Dai in Person Having a Laugh, 2021, Oil on canvas, 250×300 cm. Courtesy the artist.

Liu Xiaodong, Ning Dai in Person Having a Laugh, 2021, Oil on canvas, 250×300 cm. Courtesy the artist.

Liu Xiaodong, Changing a Lamp, 2021, Oil on canvas, 250×300 cm. Courtesy the artist.

Liu Xiaodong, Changing a Lamp, 2021, Oil on canvas, 250×300 cm. Courtesy the artist.

Beyond the scenes, the tools or “things” become a kind of externalization when an artist tries to approach the other. In addition to the straightforward whisky, Liu Xiaodong arranged more symbolic objects in the picture, which can be played by the character being painted, leading the viewer to further reverie and interpretation.

Liu Xiaodong, Erecting a Pillar 2, 2021, Watercolor on paper, 34×25.5 cm. Courtesy the artist.

Liu Xiaodong, Erecting a Pillar 2, 2021, Watercolor on paper, 34×25.5 cm. Courtesy the artist.

The radish in his mother’s hand, the light bulb in his brother’s hand, the shovel, etc. are related to work and life; cigarettes, whisky, pliers, braziers do not seem to be directly related to the protagonist at the level of labour. Liu Xiaodong did not ask Wang Xiaoshuai and Zhang Yuan to carry their cameras and he did not ask Ah Cheng to hold a pen. Objects are obviously more spiritual in the artist’s gaze on individual intellectuals. The removal of tools allows the subject being sketched to obtain a natural and comfortable state, which further becomes the “grasp” for the extension of the subject’s spirit. However, this layer of implicit expression gave way to the expression of “middle-aged and elderly people” (the artist’s expression) in the exhibition, escaping from the over-intellectualization of art in contemporary art exhibitions.

Liu Xiaodong, Mom, 2020, Oil on canvas, 150×140 cm. Courtesy the artist.

Liu Xiaodong, Mom, 2020, Oil on canvas, 150×140 cm. Courtesy the artist.

From his solo exhibition “Hometown Boy” in 2010 to the latest solo exhibition “Your Friends” in 2022, Liu Xiaodong has returned to his personal life from the social scenes he was good at handling, and social expression has been transferred to personal emotions. The artist chose to use the most traditional method in plastic arts to bring back the audience who had long been used to being driven thousands of miles away. “Your friends” was not named “my friends”, and it comes from Liu Xiaodong’s desire to cancel the “me” in this series. The self-expression that has been accomplished through neorealism has been transformed into a long-term gaze at the people around him, further into the exploration and confession of the issues on time, love, life and death.

Liu Xiaodong, Self-Portrait, 2010, Oil on canvas, 38×33 cm. Courtesy UCCA Center for Contemporary Art.

Liu Xiaodong, Self-Portrait in the Kitchen (Black Ink), 2021, Ink on paper, 31×31 cm. Courtesy the artist.

Liu Xiaodong, Self-Portrait in the Kitchen (Black Ink), 2021, Ink on paper, 31×31 cm. Courtesy the artist.

From another perspective, “Your Friends” is also an exhibition in the post-pandemic era. The tragedy caused by the disaster, the realization of disease, aging and death, make everyone, including the artist, suddenly realize the importance of an individual life. As a painter that records life, painting is not only to express, but also to remember, painting is an instinct to resist death and oblivion, the same drive that prompted the unknown Egyptian artist to make a portrait of Fayoum, and also the same one that impelled the inhabitants of Pompeii left a woman surrounded by lilies on the wall.

In the face of disease and death, art still has the ability to summon something transcendent and pull people back to a world full of birth, aging, sickness and death. In this realistic world, which is far from the smoothness of the Metaverse and still has rough edges, memories and emotions are still the main components of most people, and people are thus holding on to a fading consensus about love, life and death.

Text by Mengxi, trans. by Sue/CAFA ART INFO

Image Courtesy UCCA Center for Contemporary Art.

References:

1. Belting H. (2017). Faces: Eine Geschichte des Gesichts [M], trans. Shi Jingzhou. Beijing: Peking University Press.

2. Ibid.

3. Documentary materials about Liu Xiaodong’s Diaries displayed at the exhibition.

About the exhibition

Dates: 2022.1.15 - 2022.4.10

Venue: Central Gallery & New Gallery, UCCA Beijing

Address: 798, No. 4 Jiuxianqiao Street, Beijing