This is the initial part of the presentation made by Darren Newbury at the “Yingxiang Today”–the Fifth Annual Conference of CCVA. Darren Newbury is Professor of Photography at Birmingham Institute of Art and Design, Birmingham City University. For more information and the complete version of this paper, please contact him by E-mail: Darren.newbury@bcu.ac.uk.

Images seem to speak to the eye, but they are really addressed to the mind. They are ways of thinking, in the guise of ways of seeing.

Wilson Duff

I think it is useful before I begin this paper proper to make clear the position I’m speaking from. First, a confession: I am a lapsed photographer. I trained as photographer in the 1980s, but for a variety of reasons have ended up making a career as someone who researches, writes about and, more recently, curates photographs. All these are practices too, but I am not speaking as a photographic practitioner. I am approaching the medium as ones who works with, rather than produces, photographs; though I’d like to think I have an informed understanding of what it means to make photographs (something that can on occasion be absent from photographic theory). My own history of working with photography sits within a context where, as specialist research on the medium has deepened, at the same time there has been explosion of interest across the disciplines in what might be rather loosely termed ‘the visual’. In the last couple of decades photography has become prevalent across the social sciences and humanities as an object of study, a methodological tool and a means of presentation. These developments are of interest to me and, at the risk of provocation, I might even argue that the most interesting thinking and writing about photography has come from disciplines that have until recently shown only a marginal interest in the medium, notably anthropology. To a large degree my thoughts are directed towards this space of intersection where photographic practice and research meet, what I am calling visual scholarship. If this is distinct from the domain of photography, I think there is sufficient overlap to make it worth an on-going dialogue. I am also limiting my discussion today to the issues that arise in the process of including photographs in research and academic publishing. If some of what I say sounds like telling photographers how to suck eggs, I apologise in advance. But, at the same time, I think these practical issues are inseparable from important questions of philosophy and theory. Practitioners might also reflect on the extent to which photography is a medium that lends itself to appropriation, constructing neat boundaries around the medium is a project doomed to failure. At heart, I am talking about the multiple and complex relationship between words and images, something which I believe concerns us all.

The paper has two points of departure, a quotation, which I will come to in a moment, and a short pedagogic story. First, the story; my own visual education began, formally at least, with a vocational diploma in photography. The incident I recall took place early on in the course. I happened to be wandering along the corridor holding in my hand some 35mm black and white negatives I had developed. One of my tutors, heading in the opposite direction, stopped and challenged me. Why were the negatives not in sleeves? What on earth was I doing wandering around the dusty college corridors with vulnerable negatives in my hand? Did I not care about the images? It was this last question that struck home most forcefully. Whether or not I realised it at the time, one of the central things I was being taught was to care about, and for, images. The pedagogic implications that flow from this point will provide something of a refrain in this paper. I want to be provocative and argue that the developing field of visual scholarship has yet to fully learn how to care for images. I am sure that most practitioners would argue it doesn’t apply to them, and equally I’m sure they’re right. But it is certainly true of some work across the humanities and social sciences, where photography and ‘the visual’ is a growing area of interest. Maybe it is just the inevitable consequence of this diversified field of research and scholarship that is emerging around photography: books devoted to visual research are not always a good advertisement for the use of images it seems to me. But maybe the digital revolution also has something to do with it, the expense and preciousness of film no longer the factor it once was. Either way this is something that seems particularly evident to me in the area of academic publishing.

I do not mean to minimise the challenges visual scholars face in the context of academic publishing practice. Doing visual publishing well involves extra work and cost. And I can tell my own stories of frustration from trying to lever attention to the careful use of visual material into a process than can seem designed to exclude such attention; sometimes I have succeeded, sometimes I have failed. But real as these challenges are I am not convinced that within this broad field of academic enquiry we are doing all that we should to educate the attention of scholars, students and publishers, or even that there is a broad consensus on what is at stake. If researchers are required to argue for the value of images in the published presentation of their research, then it is important they understand precisely what they are arguing for.

As I noted this paper is principally concerned with the practical decisions and consequences of working with images. However, underlying the discussion is a theoretical argument about images and their intellectual respectability, something that tends to be taken for granted with words and numbers. This brings me to the quotation, about which I want to say two things. First, the link it draws between images and thought is important to those whose academic endeavour involves grappling with visual meaning. Duff draws our attention to the complex communication and expression that takes place when images are made and viewed, and their capacity to embody ideas and theories. Second, however, it serves to alert us to a trap, one whose long history, in Western thought at least, casts doubt on the testimony of images, and which risks undermining the case for visual presentation. I am referring to the neat separation Duff makes between the eye and the mind, sensory experience and thought, and the suggestion that the appeal of images to the former is inherently deceitful, demanding vigilance on the part of the thinking viewer. Little wonder that so much scholarship is devoted to visual critique, the unveiling of images so to speak. This way of thinking has consequences for the field of visual studies. It underpins the privileging of talking and writing about images over working with them, the dominance of the intellectual over the sensory. Too much attention to images is seen as suspect, a concern with mere aesthetic matters over the serious business of research and knowledge. Ironically, the flipside of this is a degree of nervousness and caution; a fear that one will fall into the trap set by the image and be seduced, losing control of meaning. Researchers are concerned that they might be misunderstood, and take refuge rather too quickly in loose arguments about their polysemic nature. I don’t wish to dismiss such concerns entirely, but it seems to me this failure of nerve is both symptomatic of, and made possible by, the idea that images are less knowledge bearing than words or numbers. Anyone who works with words or numbers knows very well that they too must be disciplined if they are to do what is asked of them, and even then they can often elude the writer’s grasp. Nevertheless, we continue to struggle with them because they are at the very core of academic work. Surely by the same standard it is the task of visual scholars to grapple with the complexities involved in working with images, not to withdraw from them.

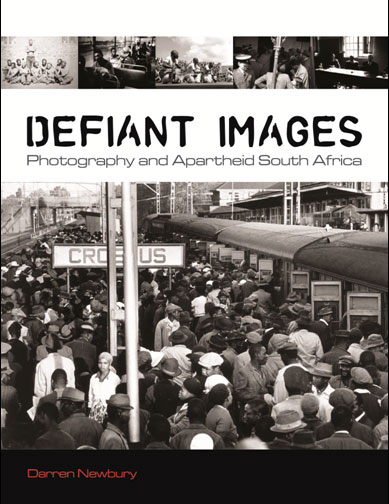

DEFIANT IMAGES BY Darren Newbury

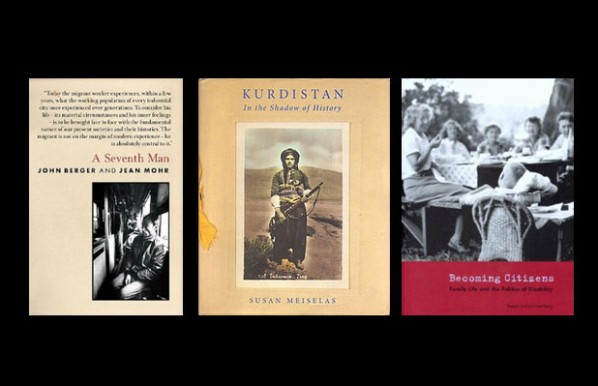

I don’t intend to pursue the philosophical debate further, but simply ask that you to keep in mind two propositions that inform my thinking. The first is the idea that the aesthetic cannot be neatly divided from the intellectual, that the address to the mind is inseparable from the address to the eye. Images are not ideas in disguise, but are themselves, on many occasions at least, intellectual formulations, material forms of expression that have to be won no less than the well-crafted sentence. The second idea is that visual scholars should be attempting not just to illustrate written arguments, but to do things with images. As Alfred Gell (1998) has argued convincingly, images have agency; and, significantly, for those arguments that suggest it is desirable to separate the information content of images from their form, the captivation of the attention of the viewer represents a ‘primordial kind of artistic agency’ (1998: 68-9). The point I want to make here is straightforward: if researchers recognise images as a primary means of achieving the ends they seek they will treat them with more care. Maybe this means visual research and scholarship coming a little closer to practice.

What does it mean to care about images? Of course this is not simply a matter of looking after them in any narrow sense, which at the extreme is simply to fetishise the image as object. But maybe it does start with a concern for the image in its own right. In this sense, it has an ethical dimension; we have a duty of care to images. Many of the images that are of concern to researchers have lives beyond the specific research project; we might use the idea of image biographies. Researchers therefore have a responsibility to consider the impact of their own uses within the life of an image. To cite Gell again, images can be conceived of as complex distributed extensions of the agency of those who have made them or owned them or shaped them in some way. Researchers should ask how they are inflecting this agency, how they are harnessing it towards their own ends, amplifying it or even attempting to undermine it, through critique for example. If visual scholars are to engage with the full complexity of images as images, then they must, of necessity, think reflexively about what they, too, are doing with them. Of course, this more relational view of the image is one of the things that research in anthropology and sociology brings to the discussion of photographs, and has consequences for practice too I believe.

There are many issues at stake here, and this paper is only a modest contribution to a much longer debate. Nevertheless, I believe much of what I say here has implications that extend both forwards and back. My examples come largely from academic print publishing, but I believe the arguments are relevant to any occasion when images are inserted into a process of intellectual enquiry.

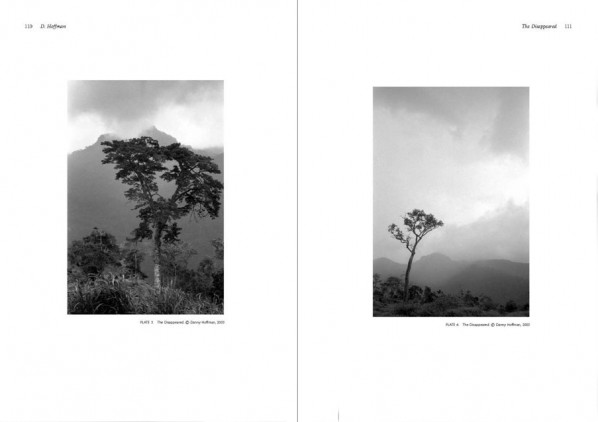

The discussion is based in large part on my experiences as editor of the journal Visual Studies over the past eight years, as well as considerations that have arisen in the publication of my own research on photography. Most of the examples I have to show you were published in the journal. These examples are the ones that I know best. The fact that I have played a part in shaping them has the benefit of enabling me to reflect on the thinking and decision making that made them appear the way they do. There are of course many other examples that demonstrate a thoughtful and intelligent approach to the use of images, some of which I may touch on if there is time. It would no doubt be instructive to consider negative examples; those cases, of which there are not a few, where the use of images leaves a lot to be desired. However, for ethical reasons such examples are perhaps better discussed in less public contexts.