Organized by the Shenzhen Municipal People’s Government and hosted by the Shenzhen Fine Art Institute, Guan Shanyue Art Museum, “The 8th International Ink Art Biennale of Shenzhen” was unveiled at the Guan Shanyue Art Museum on December 1. It showcases ink works by 53 artists. Fu Xiaodong who serves as the curator tries to resort the typical image developed in the five kinds of historical process to discuss and analyze special Chinese ways of thinking behind these images. The exhibition will remain on view until December 17.

Images of Ink Art • Research on Prototypes

Foreword by Fu Xiaodong (Curator)Contemporary visual art has increasingly geared to the tendency of globalization as well as interdisciplinarity in horizonal dimension and integration of the past and the future possibility of anthropology in vertical dimension. This year’s biennale focuses on “media of ink and brush”, intending to seek out the residues of collective unconsciousness left in the cultural baptism of globalized media from the ancient source, and the underlying coherence between the numerous works and the tradition of Chinese visual thinking which conveys meaning by images.

From the ancient times to the present, Chinese civilization has produced an ongoing sequence of meaningful images. Even before the written language appeared, there already existed a long period of time when people recorded the world in terms of images, used images to convey meaning, and employed images to perpetuate the ideals of a historical period. From Zhouyi • Xici Part One, we have a statement often interpreted to describe the origin of the Eight Trigrams (bagua), one of the earliest pictorial systems, by the sage Fu Xi: “The Yellow River gave forth the map, and from Luo River came the chart, both of which the sages took advantage.” The legendary Fu Xi “derived the eight trigrams to get enlightenment from the deities and to cultivate people”. With the origins of Chinese pictorial culture beginning with “Map of the Yellow River”, “Book of Luo River” and the “Eight Trigrams” several centuries ago, clearly the academic study of image occupies an important position in contemporary art criticism. This exhibition utilizes the ancient and long-established historical cultural traditions of the Chinese people (including diagrammatic study and epigraphy), as well as the introduction of Western-influenced cultural factors (including archeology and iconography) to carry out a comprehensive comparative study into the connections between historical art images and contemporary visual culture. By employing China’s extensive historical database of images, we can re-categorize the typical images that appear in different historical periods and cultural contexts to derive the collective memory of ancient times by discovering recurring visual themes, as well as changing circumstances. A fresh look at these images reveals that they, deeply rooted in subconsciousness, are constantly recalled from the abyss of image memory. Awareness of certain images crosses over the bounds of geography, time, form and media; images appear and reappear in literature, folk patterns and works of art historical importance. In the study of images, it is clear that images also develop over time - their significance and forms may persist or evolve, reflecting larger cultural developments and migrations. So too we know that images hold great power; images can arouse intense, irrational emotional responses in their viewers, sometimes on a subconscious level. Thus, in the construction of China’s cultural identity, we must be aware not to erase the visual memory of the collective unconsciousness, but to rethink and reexamine the local Chinese cultural roots of these images, which appear over and over again in the process of modern-day globalization and consumerism, and get new vigor.

This exhibition re-categorizes contemporary art in terms of five prototypical image types from Chinese art history; these archetypal forms serve as a comparative model for discussion about the principles and concepts underlying images.

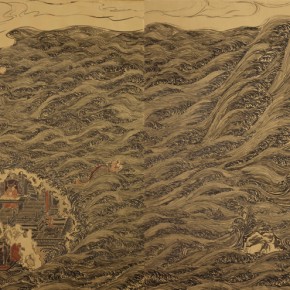

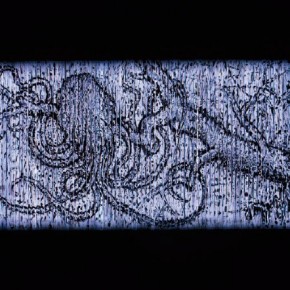

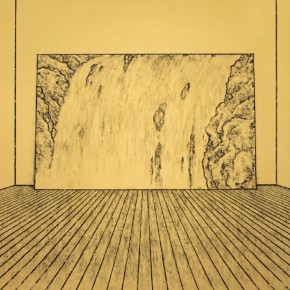

Section One: “Pavilion of Clouds and Water”

Clouds and water is correspondent to “sunyata (emptiness)” in Chinese painting. Clouds and water appears repeatedly as “image” and “background” in traditional Chinese painting. For instance, in landscape painting mountain is metaphorized as human body, water is a symbol of ongoing mind, waterfall represents circulation, boat means ferry and a leisurely state, and clouds and mist symbolizes the existence of Tao in an implicit way. In The Diamond Sutra there is a saying goes like “Form is emptiness, and emptiness indeed is form”, which reveals the philosophy of matter in Buddhism. It is a special manner of handling the visual concept of empty space in Chinese literati painting to attain tranquility, moral loftiness and to enter into infinity from emptiness. Ancient literati believe that, to create works (whether paintings or poems) that could interpret “emptiness” is a way of spiritual cultivation. Clouds and water create a symbolic spiritual state of Zen in which matter (emptiness) is formless.

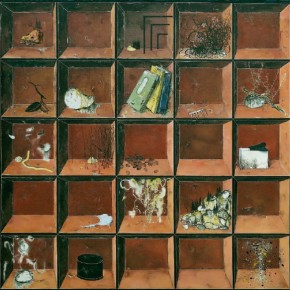

Section Two: “Flower-and-Rock Project”

“Flower-and-Rock Project” concentrates on the philosophical theories of Confucianism, particularly its “Bi De (metaphor of virtues) Theory”, which originates from “Bi Xing (metaphor)”, a figure of speech that attributes humanistic ideals to natural beauty. The so-called “Bi De Theory” refers to that some subjects of the natural world (plum, orchid, pine, bamboo, etc.) have features that are also reminiscent of man’s virtuous attributes, i.e. these natural objects take on symbolic qualities of man's moral character. Confucianism, taking lofty personality as the supreme form of beauty, wishes to cultivate people with moral virtues. Gentleness of jade, cold-tolerance of pine tree, seclusion of chrysanthemum, elegance of lotus, integrity of bamboo and pride of plum blossom is often compared to the character of a gentleman. Nature is connected with personality in a way of being a correspondent object of moral virtues other than simple visual pleasure therefore it becomes an aesthetic target. Thus, the Confucian ideal of one’s “noble character” has been historically reflected in Chinese pictorial views of the natural world, aesthetic principals of nature that continue to persist in today’s art world.

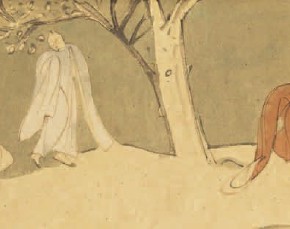

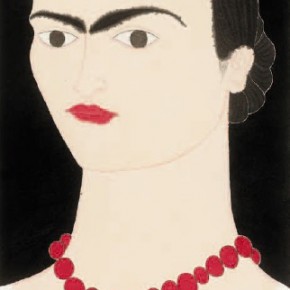

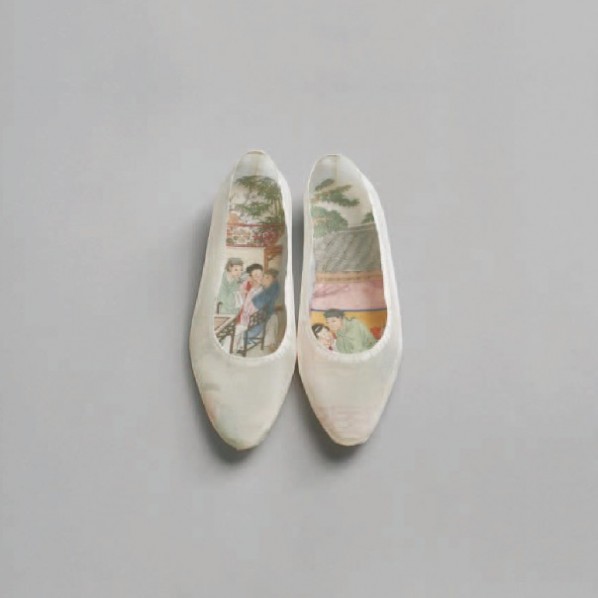

Section Three: “Goddess Biographies”

Among the continuous role of the female form in art history from the painting of Nüwa (the creator of human in Chinese mythology) unearthed at Mawangdui (King Ma’s Mound) and Xi Wang Mu to beautiful women in Nymph of the Luo River, Liao Zhai Zhi Yi (Strange Stories from A Chinese Study) and The Twelve Ladies of Jinling, female superheroes have been objects of artistic creation as well as a major subject in folk religion. The female images originate from popular beliefs of motherhood, eroticism, divinity, and ideals of beauty, and consistently have roots in mythology, shamanism, and Taoist aesthetics. Today, the imagery of the goddess remains a symbol of self-liberation and an easeful, secluded life from the secular world.

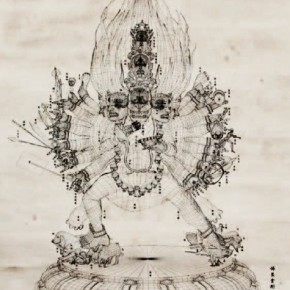

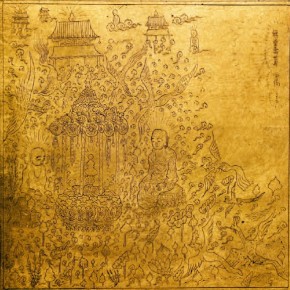

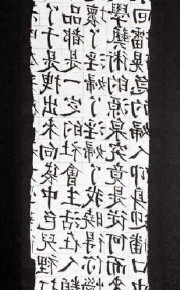

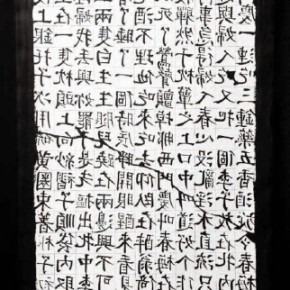

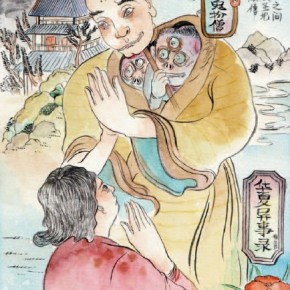

Section Four: “Buddha Statue”

Buddhism has disseminated from India to China two thousand years ago to create various major schools such as the Dharma-Character School of Buddhism, the Tiantai School of Buddhism, Pure Land Buddhism, the Ritsu school of Buddhism, Tantric Buddhism, Zen Buddhism and the Three Treatise School, etc. Modeling of Buddha statue, varying from schools to dynasties, has been increasingly sinicized together with Buddhist instruments and their meanings. In modeling of Buddhist statues, such as Tibetan Tangkas, religious images take on characteristics from local and traditional arts and provide national paradigms in the aspect of form, way of combination, image features and its relationship with traditional art. Buddha statue is not for mere aesthetic purpose, but a belief of scared items that serves religion. Symbols are connected to religious belief to form a complete ideographic system. Therefore, artists who are engaged in contemporary visual art employ knowledge and resources instead of apparent forms of this system in a more open manner.

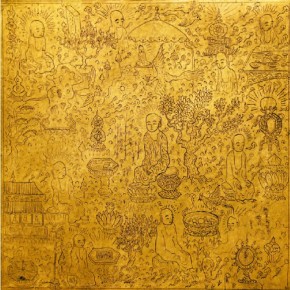

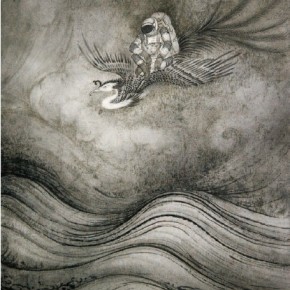

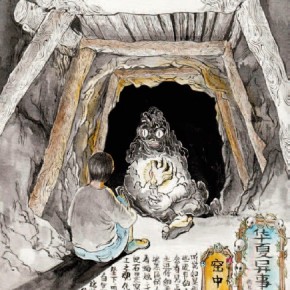

Section Five: “The Classic of Mountains and Seas”

This section concentrates on the Chinese narrative tradition. The Classic of Mountains and Seas, one of the pre-Qin great texts, is featuring ideas of history, geography, ethnicity, biology, elements, minerals, medicine, and many other aspects of traditional Chinese mythology and folklore. This book becomes classic for its interdisciplinary knowledge, fantastic myths and romantic style. As an example which rethinks classical narratology, the book is open and diverse. It symbolizes and metaphorizes history and turns logical truth into imaginary truth. With its hobby for weird things, it enables words to create another reality in another world – a riddle. Records about different topics, note-style novels and ghost novels become unique Chinese folk narratology and motifs.

This exhibition is divided into five sections, and we have made every effort to present literature, historical images and works from contemporary ink artists at the exhibition. In China, ink and bush is more than media – it represents a complete set of concept and a cultural system in a larger sense. We will discover much more besides visual experience at this exhibition.

"Research on Prototypes"Artists:

Section One: “Pavilion of Clouds and Water”:

Dong Dawei (Bei Jing · CN) Du Xiaotong (Yan Tai · CN) Hua Jun (Hang Zhou · CN) Lin Yusi (Shen Zhen · CN)

Ni Youyu (Shang Hai · CN) Shen Ruijun (Guang Zhou · CN) Ta Ke (New York, USA) Wang Suliu (Wen Zhou · CN)

Wu Qiang (Hang Zhou · CN) Yang Dazhi (Shen Yang · CN)

Section Two: “Flower-and-Rock Project”:

Dong Wensheng (Su Zhou · CN) Fan Anxiang (Hang Shi · CN) Hang Chunhui (Beijing · CN) Hao Jiantao (Chongqing · CN)

Jiang Zhi (Beijing · CN) Rachel Kneebone (London · EN) Liang Shuo (Beijing · CN) Peng Xiangfei (Beijing · CN)

Qi Lan (Shang Hai · CN) Qin Ai (Nanjing · CN) Shen Liang (Beijing · CN) Shi Jinsong (Beijing · CN) Xiao Xu (Chongqing · CN)

Yao Yuan (Nanjing · CN)

Section Three: “Goddess Biographies”:

Dong Tianhao (Hangzhou · CN) Duan Jianyu (Guangzhou · CN) Guan Yuepeng (Shenyang · CN) Huang Dan (Beijing · CN)

Li Jia (Shenyang · CN) Li Jiaru (Datong · CN) Liu Qi (Jinan · CN) Lu Dadong (Hangzhou · CN) Pan Wenxun (Hangzhou · CN)

Peng Wei (Beijing · CN) Wang Yu (Beijing · CN) Xu Hualing (Beijing · CN) Zhang Jian (Beijing · CN) Zhu Zhengming (Beijing · CN)

Section Four: “Buddha Statue”:

Li Hongbo (Ji Lin · CN) Li Tong (Hangzhou · CN) Lin Haizhong (Hangzhou · CN) Lu Yang (Shanghai · CN) Ma Jun (Tianjin · CN)

Tao Yi (Shanghai · CN) Xie Zhenliang (Shenyang · CN) Yu Ji (Shanghai · CN) Zeng Yang (Beijing · CN) Zhao Zhao ( Beijing · CN)

Section Five: “The Classic of Mountains and Seas”:

Chen Xiaoyu (Beijng · CN) Hao Liang (Beijing · CN) Liu Yi (Hangzhou · CN) Wu Jian'an (Beijing · CN) Wu Junyong (Hangzhou · CN)

Zhao Peng (Beijing · CN)

About the exhibition

Curator: Fu Xiaodong

Duration: December 1st,2013 to December 17th,2013

Venue: Guan Shanyue Art Museum

Sponsor: Shenzhen Municipal People's Government

Organizers: Shenzhen Fine Art Institute, Guan Shanyue Art Museum

Courtesy of the artists and The 8th International Ink Art Biennale of Shenzhen.