At 6:00pm daily from May 26 to May 29, 2014, jointly hosted by the School of Humanities, CAFA (the Central Academy of Fine Arts), Institute of Plastic Arts, and Department of Postgraduate, Indian Buddhist Art series of lectures were held at the CAFA library lecture hall, Professor Anupa Pande, Head of Department of History of Art, Dean of National Museum Institute of History of Art, Conservation and Museology, National Museum, New Delhi, India was invited to be the speaker.

Professor Anupa Pande is currently a member of the International Buddhist Research Council. She has been engaged in education and research for more than 30 years, published as much as 7 books on Buddhist art and Indian history and culture, issued more than 40 professional papers.

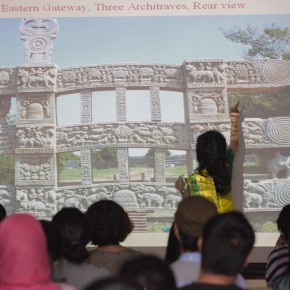

The series of lectures included a total of four sessions, the first session was held at 6:00pm on May 26, 2014, entitled “Indian Early Buddhist Art – The Great Stupa at Sanchi (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sanchi)”, Professor Anupa Pande mainly took the stories of reliefs of The Great Stupa at Sanchi as an example, to introduce the early Indian Buddhist art to audiences.

The Great Stupa at Sanchi was originally built in the 3rd century – the first century BC, located in central India. The paradox of Buddhist art is that Buddha rejected performance itself in any art form, while the early Buddhist art in India beautifully performed the images of Buddha, it mainly used symbolic techniques, such as ficus religiosa, dharmacakra, Buddha, Dhama, and Sangha, Buddha’s footprints, Parasol, etc were the symbolic expression of the images of Buddha. After that Professor Anupa Pande introduced the embossed images on the pillars of the four gates in detail and the cross beams of the Great Stupa, from south, to north, east, and west in turn. In addition, Professor Anupa Pande also put forward some interesting new ideas.

At 6:00 pm on May 27, 2014, the second session of the Indian Buddhist Art was held, Professor Anupa Pande focused on two issues: first of all, why were the images of Buddha performed using idols instead of as previously understood refusing the use of idol, and the related discussions including the ideas of Professor Anupa Pande; secondly the developments and evolutions of the three styles of Buddhist sculptures, namely the characteristics of the figures of Buddha in the districts of Gandhara, Mathura, and Sarnath. The early Buddhist artistic images were completed in the districts of Gandhara and Mathura. In Mathura, it was popular to worship Yasha, directly affecting the creation of the images of Buddha. In Gandhara, Buddha’s images presented a Greek style, namely the Apollo style. The two styles both borrowed from local popular traditions, and then began to interactively influence and communicate with each other.

When she was asked why the Buddha’s eyes were slightly closed in the mature era instead of completely open in the early era, Professor Anupa Pande answered: when the eyes of Buddha are completely open, he was more like a king looking at the secular world, but then people made his eyes slightly close to express that Buddha began to reflect on his heart, synchronising by reflecting on two worlds, revealing he was thoroughly enlightened.

At 6: 00 pm on May 28, 2014, Professor Anupa Pande gave the third lecture entitled Mural Paintings of Ajanta Caves and Bagh Caves in the Gupta Dynasty. It was in the period of Wei, Jin, Southern and Northern Dynasties in China, but it was mainly influenced by Chinese Buddhist art in the Tang Dynasty. Professor Anupa Pande brought a lot of images of precious mural paintings to share with the audience, and gave a detailed explanation.

The size of the Ajanta caves was not as large as Mogao Grottoes, but it was the first Buddhist caves built in India, which dates from the 2nd century BC to about 7th century AC, the caves were located in the north of Aurangabad in the Indian state of Maharashtra, made of 30 caves. According to the architectural style, the building of Ajanta Caves could be divided into two types: Buddha halls and Buddhist monastic rooms.

Regarding the theory of painting, in the comments of the Indian “Kama Sutra”, it put forward the six requirements of painting: the distinction of shape, quantity, affection, beauty, imitation, and the distinction of colors. It was interesting that it was different in approaches but equally satisfactory in result with the six principles by Chinese Xie He. The theme of Ajanta frescos is mainly based on Jataka and the Buddhist stories. The frescos of a pair of bodhisattvas on the gates of Cave 1 were very famous, showcased the perfect combination of the beauties of flesh and spirit. The conical headdress was balanced with the oval shaped face, meanwhile the lotus-shaped eyes slightly closed, with a high and straight bridge of the nose, and thick lips. It used a concave-and-convex painting approach so that the facial features seemed gentle.

On May 29, 2014, the Indian Buddhist Art series lecture 4 entitled “Buddist Narrative Art Illustrating the Virtue of Charity as Seen in Early Indian, Central Asian, South and Southeast Asian Art” was held at the CAFA library lecture hall, mainly introducing the Jataka stories to promote the spirit of alms. Different from the previous three sessions, this lecture focused on showcasing early Indian Buddhist art that radioactively influenced the surrounding areas.

Professor Anupa Pande offered a detailed explanation of the artistic expressions of the two themes of Vessantara Jataka and Sivi Jataka. At last, she added, in India, since Vedic times, alms haveplayed a part in the charity. It included giving up all the things someone had, in Brahmanism, the items of alms must be consistent with the religious provisions. But Buddhists didn’t have such a restriction, purely based on morality. In Buddhism, alms became dematerialised, people gave up not only their material wealth, but even their own bodies.

Text: Li Fan, translated by Chen Peihua and edited by Sue/CAFA ART INFO

Photo: Quan Jing/CAFA ART INFO