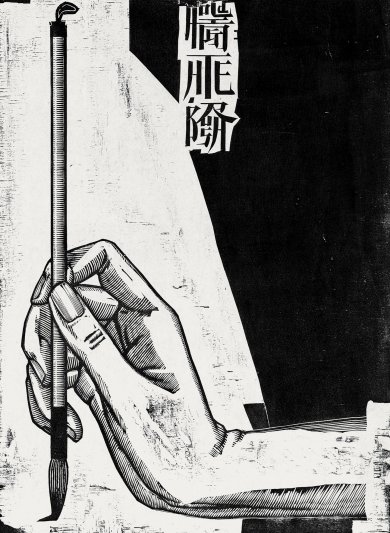

One of the highlights of the exhibition is the animated video The Character of Characters. It is a comprehensive and penetrative piece exploring the inner relationship of Chinese personalities and the language they have been using for thousands of years. The artist’s magnum opus and a personal account of the significance of Chinese language and characters through history, culminating with their significance to Chinese society today.

Chinese character "one" seen in Xu Bing's proposal for The Character of Characters, from Xu Bing's The Character of Characters: An Animation, Asian Art Museum, 2012, p. 31

Starting with the writing process of the simplest Chinese character, “one,” which also happens to be the most fundamental stroke in Chinese calligraphy, a rich and boundless world is revealed from the microscopic texture. The character reminds us of the Daode Jing (Classic of the Way of Power, the basic Daoist philosophical text) that the Dao (the void from which all reality emerges) gave birth to one, from that appeared two, then three, and from three generated the myriad things of the world.

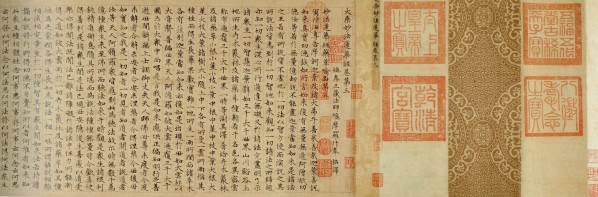

In the video, the character “one” then goes back to the calligraphy work The Sutra on the Lotus of the Sublime Dharma by Zhao Mengfu (1254–1322), the great painter, calligrapher, connoisseur, scholar, and official in the Yuan dynasty. Zhao’s calligraphy of the Lotus Sutra inspired Xu Bing to create The Character of Characters, a video commissioned by the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco for the 2012 exhibition Out of Character: Decoding Chinese Calligraphy with support from the Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation.

Zhao Mengfu, The Sutra on the Lotus of the Sublime Dharma, Guanyuan shanzhuang, collection of Jerry Yang

Zhao Mengfu in Chinese Culture

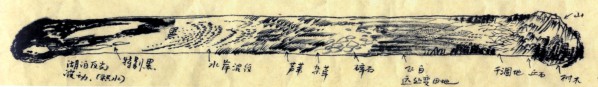

The Lotus Sutra calligraphy dissolves and reforms into Zhao Mengfu’s painting Autumn Colors on the Qiao and Hua Mountains, pointing to the shared origin of Chinese calligraphy and painting.

Zhao Mengfu, Autumn Colors on the Qiao and Hua Mountains, c. 1296, National Palace Museum, Taipei

Zhao Mengfu was a prince and descendant of the Song dynasty’s imperial family. After the Song dynasty was conquered by the Mongols, however, he accepted a post in the Mongol-ruled imperial court. Facing not only the dilemma of his identity in the transition of dynasties, Zhao also balanced his position between being an official in the “dusty world” and a Buddhist in the sacred realm. Certain shared qualities appear in Zhao Mengfu’s life and art—neutrality, passive resistance, introspection, and firmness cloaked in gentleness.

The Meaning of Symbols

Another section of the video shows a landscape painting made up of the basic elements of Chinese characters. A book is shown flying over the landscape collecting these calligraphic elements. This landscape comes from another work by Xu Bing: The Mustard Seed Garden Landscape (2010), which is displayed adjacent to the video in the gallery. In this section of the animation, Xu Bing coveys the idea that Chinese painting and calligraphy are linked not only by shared similarities in brushwork, but also by symbolism. Chinese characters are composed of different elements known as “radicals” that also symbolize concepts. By memorizing characters, our brains process combinations of various calligraphic elements: some indicate sounds, and some indicate meanings. Through calligraphy practice, the brain is trained to be sensitive to these basic elements that make up Chinese characters.

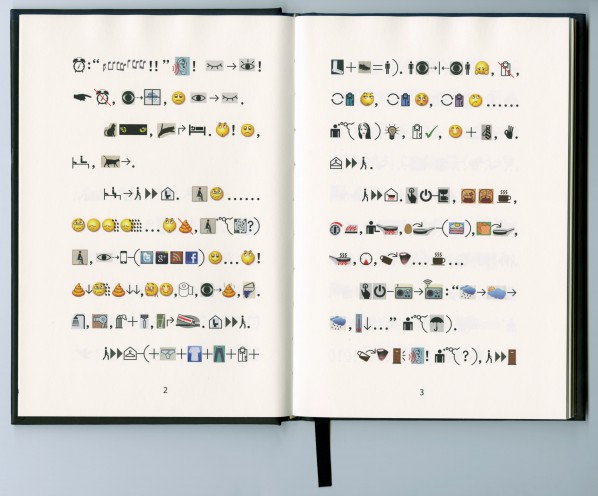

Xu Bing’s interest in symbols inspired him to make Book from the Ground, a novel written entirely in symbols. All collected from our contemporary society, these symbols are legible to anyone, regardless of their nationality, language, race, or age.

Xu Bing, Book from the Ground, the MIT Press, 2013, p. 2–3

Writing Is like a Ceremony

Sit properly, be calm, hold the brush, raise the wrist, and then start writing: every step in practicing calligraphy is almost as serious as observing a ceremony or ritual. Throughout history, there have been famous stories about learning calligraphy, expressed in such poetic language as “hanging hairs from a beam and piercing bones with an awl,” and the great calligrapher Wang Xianzhi (344–386) used up all the water in a pool to wet his brush and mix his ink when practicing calligraphy. Being taught by these stories, Chinese people have been trained in the spirit of perseverance, assiduousness, restraint, and patience. Calligraphy practicing is not only about skills of handwriting, but also about cultivating these traditional virtues.

Xu Bing, proposal for The Character of Characters, from The Character of Characters: An Animation by Xu Bing, Asian Art Museum, 2012, p. 45

“Guanxi”—“Connection” in Calligraphy

An important topic in Chinese society is the notion of “guanxi”—personal connections or relationships. Traditionally it is important to build guanxi with those of a certain social status. Seemingly irrelevant—at least initially—to calligraphy, guanxi is vividly illustrated by Xu Bing, in that his construction of a character is all about building guanxi. For each character, every stroke is placed based on the relationship with the previous one(s). The practice of calligraphy is about manifesting a harmonious guanxi for all strokes.

Guanxi is even reflected in a various social phenomena, such as traffic in China, often characterized by spontaneity and dismissal of rules on the part of drivers. Interestingly, people are able to navigate the complex traffic chaos by responding through guanxi to other drivers’ car language, just like practicing guanxi in the calligraphy.

Xu Bing, proposal for The Character of Characters, from The Character of Characters: An Animation by Xu Bing, Asian Art Museum, 2012, p. 59

Xu Bing, still from The Character of Characters, 2012, commissioned by the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco for the 2012 exhibition Out of Character: Decoding Chinese Calligraphy with support from the Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation

The installation Square Word Calligraphy Classroom, composed of tracing books with Xu Bing’s invented calligraphy, was created to help English speakers understand the language and the art of Chinese calligraphy. The work is on view in the Boone Children's Gallery, where visitors are invited to take up a brush and practice his calligraphy.

Installation view, The Language of Xu Bing, December 20, 2014 through July 26, 2015, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, photo © 2015 Museum Associates/LACMA

About the exhibition

Duration: December 20, 2014–July 26, 2015

Venue: Hammer Building, Level 2, LACMA

Courtesy of the artist, Wan Kong, Tsao Research Fellow, Chinese Art Department and LACMA, for further information please visit www.lacma.org.