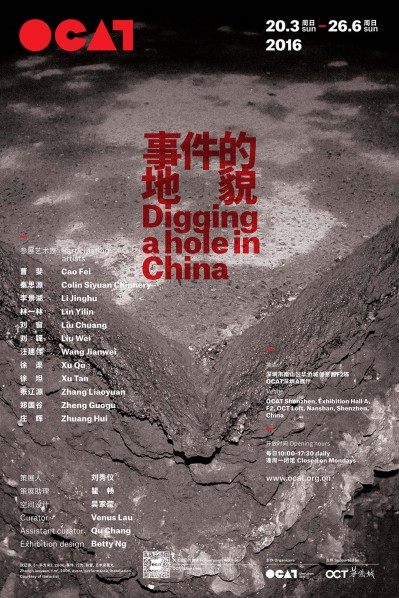

OCAT Shenzhen is proud to present the large-scale exhibition, “Digging a Hole in China,” on view from March 20 to June 26 in Exhibition Hall A. Featuring a range of works produced in contemporary China that bear a connection to land, the exhibition attempts to expose and analyze the discrepancies between this genre of work and “conventional” land art understood in the Western-centric art historical context, thereby probing the potential of “land”—as a cultural and political concept—in artistic practice.

In late 1960s, changes in the cultural and social climate around the globe led a group of Western artists to desolate places—the so-called “nowhere.” These artists employed land-related materials in their artistic productions, and demarcated themselves apart from established systems of consumer society, capital, and rigid art institutions through their geographical retreat. To them, using land was a provocative and confrontational gesture with temporal-spatial properties exceeding the fleeting exchange-value and durability of commodities. Meanwhile, in China, thousands of intellectuals were sent to rural regions as part of the “Down to the Countryside” (shang shan xia xiang) movement. Here, the concept of Land Art was imported from the West in the mid-1980s. While most of these works did not necessarily relate to their Western counterparts, and there were vast differences between the two contexts (Chinese Land Art did not necessarily take consumerism and the art market as a target, as consumerist society was still nascent), their concurrence nevertheless reveals intriguing correlations. In the past three decades in China, society has gone through groundbreaking transformations, and ontological, sociological, and political conceptualizations of land have changed drastically: an exploratory and evolving process that has been represented in diverse forms in contemporary art. Produced at different points in time from 1994 onward, the works in “Digging a Hole in China” delineate the hidden trajectory of land’s conceptual evolution. This strand of art does not attack established systems in a belligerent and explicit manner, but instead subtly exposes the epistemological framework of land in order to open up new sites beyond it.

While “traditional” Western land art seeks a conceptual and geographical nowhere, the works in “Digging a Hole in China” turn to a variety of issues such as the rights of ownership, management, and land use, and the transfer of and restrictions on these rights, weaving together a massive network that has already exceeded “land.” In Circulation: Sowing and Harvesting, Wang Jianwei accelerates the circulation of agricultural production, enacting a micro-circulation with an “invisible hand” in a post-planned-economy China. In two ensuing works, namely Production (1996) and Living Elsewhere (1998), Wang carried on his discussion of labor relations: by documenting the changes at a production site and the migratory nature of workers, the two works represent a grafting of research onto society, politics, and production. Sharing observations of land, labor, and the peasant class, the three works reflect mutually bordering relationships. From 2006 to 2007, Zhang Liaoyuan, as well as Liu Wei and Colin Chinnery (as Chen Haoyu), excavated public land on one of the main axes in Hangzhou (1m2) and in the 798 Art District in Beijing (Propitation) respectively. Aside from long negotiations with the local governments and other inconveniences during the execution of the works, the artists’ appropriation of the material used to construct public space blurs the line between public and private: Zhang cuts out a piece from the road—a material object in public space—and turns it into physical proof of his work’s conceptual underpinning, whereas the Liu-Chen duo carves symbols of land and religion on the ground of the art district that is always bustling with visitors. In his latest work, Plaza (2016), Li Jinghu cuts the marble flagstones at Dongguan’s central plaza into pieces of variable sizes, and puts them together into a pyramid-shaped monumental structure that interrogates the plaza as an architectural form and symbol of authority. Age of the Empire, an ongoing project since 2004 by Zheng Guogu (now renamed as Liao Yuan, or “Accomplished Garden”), is a land development project that echoes aspects of the titular real-time strategy game through which he played up to his initial goal: actualize the “empire’s” potential. If the growth of civilization in the virtual game-world is a glossy, flattened field void of land’s materiality, or its bureaucratic and physical elements, land construction in reality gives rise to new sites with their own codes of regulations. In this light, Cao Fei’s RMB City and Age of the Empire fashion a dialectic of the virtual and the real. In RMB City, Cao Fei constructs the many identities of a Chinese city in the online world of Second City. While realizing individual subjects’ migration to the virtual world, the artist also builds a new Chinese landscape that is—in her own words—a “condensed incarnation of contemporary Chinese cities with most of their characteristics; a series of new Chinese fantasy realms that are highly self-contradictory, inter-permeative, pan-political, extremely entertaining, and laden with irony and suspicion.”

To a great extent, Zhuang Hui’s art practice cannot be separated from the desert. Zhuang Hui Solo Exhibition (2014) sees him transplanting his previous large-scale sculptures to a deserted zone at the China-Mongolia border. The imagery of the desert is not uncommon in art: Richard Serra’s East-West/ West-East (2014) in the Qatari Dessert, James Turrell’s Roden Crater (1977) in Arizona, and Elmgreen and Dragset’s Prada Mafia (2015) in Marfa are among the most acclaimed cases. Distant, vast, and desolate, the desert is more than a topography; it is also a spiritual metaphor. A Nietzschean retreat to the desert is a “deliberate obscurity,” a “getting-out-of the way of one’s self,” to a “nowhere” that is at once intrinsic and extrinsic to humanity. Zhuang’s attachment to topography stems from his personal experience of growing up, yet this attachment also embodies the rigor and restraint of geological research. In 1995, he created and photographed more than 100 fifty-centimeter-deep holes (Longitude 109.88o E and Latitude 31.09o N, 1995–2008) at a number of spots along the Yangtze River, which would later be flooded by the Three Gorges Dam—the largest reservoir project in the world. Uninhabited land is precisely the new relief, and the second nature, in the Anthropocene era.

In Planting Geese, a video from 1994, Zheng Guogu directly employs soil and the practice of planting as a means of production, performing the symbolic and absurd act of “planting geese” to rethink the agricultural activity in the era of drastic changes in Chinese social structure. Lin Yilin’s Whose Land? Whose Art?, a site-related project made specifically for the LAND Foundation in Chiang Mai, Thailand, also testifies to a return to agriculture. Through the performance of building walls at paddy fields, the artist reconstitutes the relationship between “culture” and “agriculture”: the wall, as the separating line of “inside/ outside,” prompts contemplation of land issues.

Beyond its relationships to agricultural production, landscape also explicates the socio-geological strata of urban planning. The mixed-media work Upstream (2011) records the artist Xu Qu and a friend aimlessly rowing a dinghy upstream in a stinky creek that runs through the outskirts of Beijing, eventually arriving in the downtown area at the end of their trip. This random voyage—wherein the farther away from the urban center they are, the more enchanting the scenery they witness—reveals the inevitability of stratification in both the urban landscape and social structures. Liu Chuang’s Untitled (Dancing Partner) and Cao Fei’s East Wind are two other works from 2011 that also trace urban paths. In the former, two identical cars drive side-by-side on the highway at the lowest speed limit, while the latter records a truck disguised as Thomas, the cartoon train engine, beetling around in a city. Both works reflect and defy the rules and regulations that ethically ground road users, and reveal the different collectives divided by the designed road networks and each of their characters. In his earlier intervention work Railing (2003), Liu reconfigured a section of the guardrails by Shennan Boulevard in Shenzhen, a performance through which he plays out poetic interventions and inoffensive resistance against rigid road regulations. For many years, Xu Tan has employed the unique method of “searching with keywords” in his practice to outline the sociological structure embedded in language. He extends his field research on farmlands in the Pearl River Delta to art institutions and invites the audience to take part in an ongoing discussion on land and vegetation, thereby dismantling the elitist high-walls of sociological and linguistic studies. Cai Fei’s video Rumba II: Nomad (2015) records a domestic vacuum cleaning robot wandering around in an area slated for demolition located at Beijing’s urban fringe. The robot’s ability to automatically explore space examines human’s ever-changing spatial perceptions due to rapid urban development.

“Land” in the Western context was once a nowhere—a battle ground against various systems. In the present age, when Google Earth can teleport us anywhere with a single click, geographical distance seems to no longer offer new sites for criticism. In the face of the heated real estate market, land and capital becomes devotedly attached to consumer behavior; the sense of distance that “land” once possessed has slowly vanished, albeit with our further physical estrangement from the material. In a post-manifesto era far away from the birth of Land Art, the exhibited works engage a material plane that people share, generating fissures that can release yet unknown properties of the land—venturing into the waves while bundled up with land.

Participating artists

Cao Fei (b.1978, Guangzhou) received her B.F.A from the Department of Decorative Arts and Design at Guangdong Academy of Fine Arts in 2001. She was a nominee for the Future Generation Art Prize 2010 and the finalist of Hugo Boss Prize 2010. In 2006, She received the Best Young Artist Award from Chinese Contemporary Art Award (CCAA). Cao’s upcoming projects in 2016 include her first retrospective at MoMA PS1 and BMW Art Car #18.

Colin Siyuan Chinnery (b. 1971, Edinburgh) is an artist and curator based in Beijing. He is Director of the Wuhan Art Terminus (WH.A.T); founder of the Beijing Sound Museum, and a Contributing Editor to Frieze magazine. He was Director in 2009 and 2010 of ShContemporary Art Fair in Shanghai. Before that, Chinnery was Chief Curator/Deputy Director at the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art (UCCA) in Beijing.

Li Jinghu (b. 1972, Dongguan) graduated from the Fine Art Department at South China Normal University in 1996, and currently lives and works in Changan County, Dongguan. He recently participated in major exhibitions such as "Trace of Existence" (Ullens Center for Contemporary Art, Beijing, 2016), "The System of Objects" (Minshen Art Museum, Shanghai, 2015), “Institution Production: Ecology Investigation of Contemporary Art of Young Guangzhou Artists” (Guangdong Museum of Art, Guangzhou, 2015), amongst others.

Lin Yilin (b.1964, Guangzhou) graduated from the Department of Sculpture at Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts in 1987, and co-founded the Big Tail Elephant group in 1991. He currently lives and works in Beijing and New York City. He has participated in major exhibitions such as “The 7th Shenzhen Sculpture Biennale , Accidental Message: Art is Not a System, Not a World” (OCAT Shenzhen, 2012), “The 12th Kassel Documenta” (Kassel, 2007), and “China Avant-garde” (Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin, 1993), amongst many others.

Liu Chuang (b.1971, Hubei) graduated from Hubei Academy of Fine Arts in 2001, and currently lives and works in Beijing. His works has been shown at major exhibitions including “The System of Objects” (Minsheng Art Museum, Shanghai, 2015) and “Social Factory: the 10th Shanghai Biennale” (Power Station of Art, 2014), amongst others.

Liu Wei (b. 1972, Beijing) graduated from the Department of Oil Painting at China Academy of Art in 1996. He has participated in major exhibitions such as “Colors” (Ullens Center for Contemporary Art, Beijing, 2015), “Adventures of the Black Square: Abstract Art and Society 1915–2015” (Whitechapel Gallery, London, 2015), the 13th Biennale de Lyon (2015), and the 11th Sharjah Biennial (2013), amongst others.

Wang Jianwei (b. 1958, Sichuan) attained his M.F.A from the Department of Oil Painting at Zhejiang Academy of Art in 1978, and currently lives and works in Beijing. Wang was awarded the FCA (Foundation for Contemporary Arts) grant in 2008. In recent years, he participated in major exhibitions such as “Nonfigurative" (Shanghai 21st Century Minsheng Art Museum, 2015), "Time Temple” (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, 2014), "Yellow Signal" (Ullens Center for Contemporary Art, Beijing, 2011), amongst others.

Xu Tan (b. 1957, Wuhan) attained his M.F.A from Guangzhou Academy of Art, and is currently living and working in Guangzhou as a full-time artist. He was a member of the experimental artistic group, Big Tail Elephant, during the 1990s. He recently participated in major exhibitions such as “Linguistic Pavilion” (Minsheng Art Museum, Shanghai, 2016) and “Sharjah Biennial 12: The Past, the Present, the Possible” (2015), amongst others.

Xu Qu (b.1978, Jiangsu) attained his M.F.A in painting and film from Braunschweig University of Art in Germany in 2008, and currently lives and works in Beijing. He recently participated in major exhibitions such as “Bentu: Chinese artists in a time of turbulence and transformation” (Fondation Louis Vuitton, 2016), “Mobilization: The 3rd Ural Industrial Biennial of Contemporary Art” (Yekaterinburg, Russia, 2015), and “COSMOS” (Shanghai 21st Century Art Museum, 2014).

Zhang Liaoyuan (b.1980, Weifang, Shandong) graduated from China Academy of Art in 2006, and currently lives and works in Hangzhou. His works have been included in major exhibitions such as “ON|OFF: China’s Young Artists in Concept and Practice” (Ullens Center for Contemporary Art, 2013) and “Thirty Years of Chinese Contemporary Art—Moving Image in China 1988-2011”(Minsheng Art Museum, Shanghai, 2013), amongst many others.

Zheng Guogu (b.1970, Yangjiang, Guangdong) graduated from the Department of Printmaking at Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts in 1992, and is the co-founder of Yang Jiang Group (2002-present). He recently participated in various major exhibitions including “Zheng Guogu: Ubiquitous Plasma” (OCAT Xi’an, 2015), “Humanistic Nature and Society (Shan-Shui)—An Insight into the Future” (Collateral Event of the 56th International Art Exhibition - la Biennale di Venezia, 2015), and “Breaking Forecast: 8 Key Figures of China's New Generation Artists” (Ullens Center Contemporary Art, 2009).

Zhuang Hui (b.1963, Yumen, Gansu) is an independent artist who currently resides in Beijing. His recent solo exhibitions include “Zhuang Hui Solo Exhibition Project” (OCAT Xi’an, 2015) and “Yumen 2006-2009: A Photography Project, Zhang Hui & Dan’er” (Three Shadows Photography Art Center, Beijing, 2009).

About OCAT Shenzhen

Established in 2005, OCAT became a registered, independent non-profit organization in April 2012, and built a group of contemporary museums of art across China. With its headquarters in Shenzhen, the museum group comprises OCAT Shenzhen, OCT Art & Design Gallery (Shenzhen), OCAT Shanghai, OCAT Xi’an, and OCAT Institute (Beijing). As the first art establishment among the OCAT museums, OCAT Shenzhen has a long-term commitment to the practice and research in the field of contemporary art and theory both inside of China and in the international arena.

About the exhibition

Dates: March 20 - June 26, 2016

Venue: Exhibition Hall A, OCAT Shenzhen

Artists: Cao Fei, Colin Siyuan Chinnery, Li Jinghu, Lin Yilin, Liu Chuang, Liu Wei, Wang Jianwei, Xu Qu, Xu Tan, Zhang Liaoyuan, Zheng Guogu, Zhuang Hui

Curator: Venus Lau

Opening Reception: March 20, 2016, 5pm

Courtesy of the artists and OCAT Shenzhen, for further information please visit www.ocat.org.cn.