By Qi Xing

Several years ago I saw some recent works by Jiupeng in his studio and was particularly moved by a black and white painting featuring a scale with Buddha’s head on one side and excrement on the other. “Since everything is born from thought, there is no difference between prajnā, i.e., highest wisdom, and filth.” To me, that is what I guessed the painting was intended to convey.

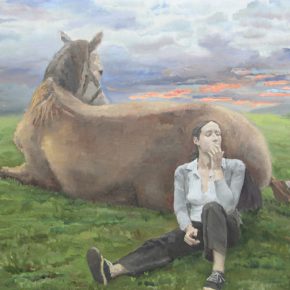

I happened to be working on several Buddhism-themed paintings during that time, the one featuring a monk and a tiger amongst others. Theme-wise, mine was by no means special in this category, as the arhat and his prostrated tiger make up one of the most common themes in Buddhist paintings. After all, Buddhist scriptures are dotted with merciful stories about Buddhists who are willing to sacrifice their lives as food for animals.

We had planned a joint exhibition for these Buddhism-themed works under the title “Under the Stress of Forever”.

The title comes from a love poem by Li Juan, a writer from Xinjiang:

“I’m in a place that is faraway. So faraway that you would die on your way to seek me ... I spent too much of my time in waiting. My time remaining is not even enough to experience the shortest of loves … Therefore I start alone, for I cannot wait any longer.”

According to Beihuajing (Beihua, i.e., merciful lotus), Sakyamuni vowed in his previous life to the Bodhisattvas in nirvana that he would volunteer to be sent to the chaotic earthly world where he is willing to suffer for the sin of all the living creatures in the name of Saddhamma until the world is free of dukkha.

We talked about this exhibition with Ni Jun in hopes that he would write us some remarks or give some advice, but we were pleasantly surprised that he preferred to participate in the exhibition.

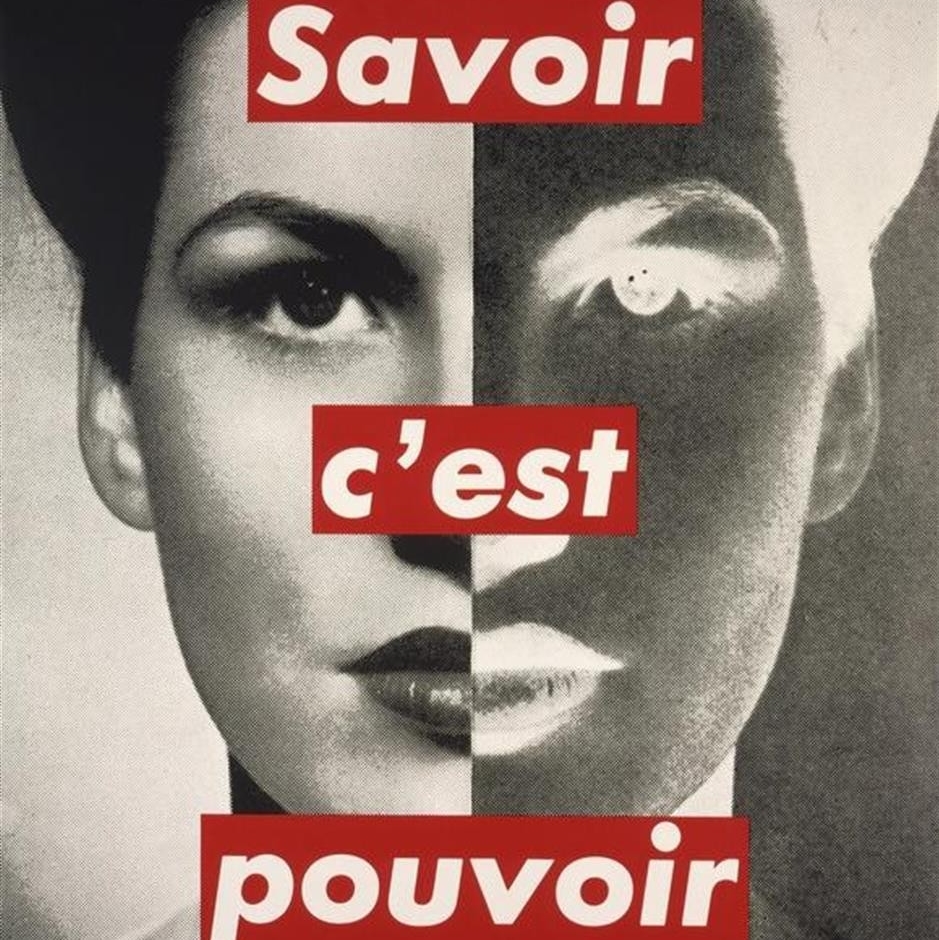

Afterwards, we three met frequently to discuss a variety of topics, like the relationship between classical art and Christianity in the West, the origin of Western Modernism and Judaism, what hyper-correction radical art views have led to, how avant-garde art that boasts subversion is once again being capitalized and institutionalized, and Chinese contemporary art that copies the west slavishly for the sake of modernization, etc.

We benefited immensely from these conversations. For two students, it was a tremendous honor to work with Mr. Ni for an exhibition. However, our thoughts had developed astray from our original plan on Buddhism, thus we needed a new title. One day Jingyuan, a friend of ours, happened to be with us during a conversation. “Yuyuantan”, she blurted out, “It is a place that actually exists.”

“In the old days, spring bubbled in Yuyuantan all year round. Due to its low-lying topography, water from the Western Hill stopped here, carving out the beautiful landscape filled with birds flying and perching around.

In the Qing Dynasty, Yuyuantan was on the verge of drying up due to the low underground water level. During the 38th year of Emperor Qianlong’s reign (1773), waters from the Western Hill were channeled into Yuyuantan, not only reviving the deep pool but also reducing floods in the villages along the way.

After the PRC was founded, Beijing’s Municipal government realigned Yuyuantan with the upstream and downstream river-ways as well as adding two new ponds, turning it into a hub for flood detention. From then on, water from Guanting Reservoir and Miyun Reservoir flowed into Yongdinghe Diversion Canal and Jingmi Diversion Canal to pass through Yuyuantan before finally entering the rivers and ponds in the south of Beijing.

Sitting between the East Diaoyutai and the West Diaoyutai, Yuyuantan used to be an imperial garden but is now a people’s park that plays important roles in water diversion, water storage and flood control.”

The three characters, “yu”, “yuan” and “tan”— jade, abyss and pond — represent imagery as separate individuals and together as one. The actual geographic existence of a pool called Yuyuantan reminds us of the saying “you are what you eat”. In a way, it tells us of the role geographic elements play in a person’s development. The title “Yuyuantan” therefore symbolizes the irreplaceability of local experience.

Painting is a process of accumulation and internalization of experience, as well as slow and steady growth, which are qualities valued by all the artists involved in this exhibition.

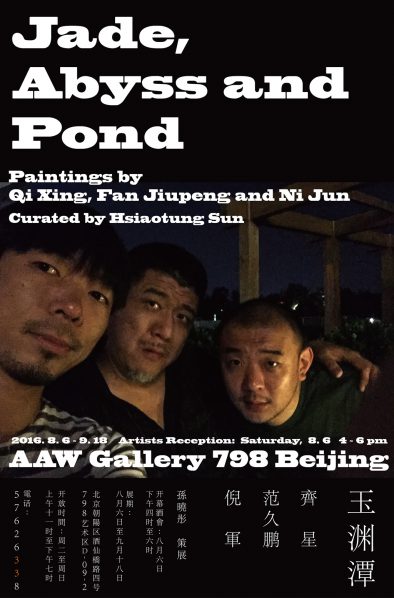

About the exhibition

Dates: August 6 — September 18, 2016

Venue: AAW Gallery

Artists Reception: August 6, 4:00—6:00pm

Courtesy of the artist and AAW Gallery.