Pierre Macherey quoted in Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, “Can the Subaltern Speak?” in C. Nelson and L. Grossberg (eds.), Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, Macmillan Education: Basingstoke, 1988, pp. 271-313

The social network of Pan Yuliang’s early career as a modernist artist and an art educator in the period of the Republic of China resonated with larger social-political movements at that time: from the cultural construct of “New Woman” and the New Culture Movement, to the revolution and reform launched by the Nationalist Party and early Communists and the rise of modern nationalism in China, and from the end of World War I to the Japanese Invasion in 1937. While many of her male peers and acquaintances with western educational background advocated their social, political, and cultural visions in public, and made their way into mainstream history, Pan Yuliang’s own accounts related to major decisions on changes in her life and her artistic motivation are nowhere to be found. The silent journey continued beyond her return to Paris in 1937, and she left no written commentary regarding her concept for “Quatre artistes chinoises contemporaines”, which opened in 1977 in Musée Cernuschi in Paris. For this particular exhibition, Pan Yuliang extended the solo invitation to include three other woman artists, who worked in traditional art forms and were all part of the Chinese diaspora.

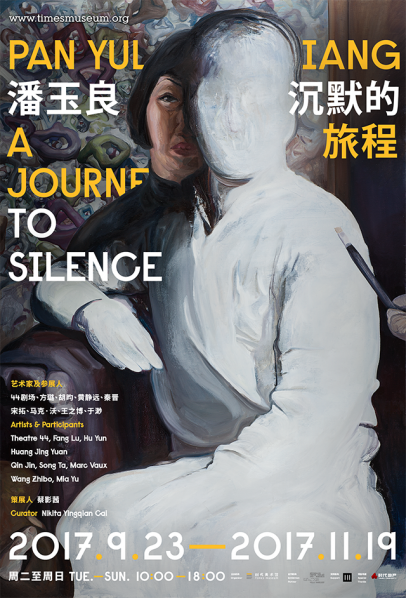

Inspired by Pan Yuliang and her decision to open the 1977 exhibition to others, this May in Paris, the exhibition Pan Yuliang: A Journey to Silence invited artists Hu Yun, Huang Jing Yuan, Wang Zhibo and art historian Mia Yu to form a research group functions as a collective subjective agency. Following that in September, the second chapter at Times Museum, invites Theatre 44, Fang Lu, Qin Jin and Song Ta to join in with their new commissions arising from Pan Yuliang and responding to the exhibition. Due to the inaccessibility of Pan’s original paintings, this is by no means a retrospective exhibition. Departing from the idea of representing Pan Yuliang by claiming new territories of authority or the delusion of bringing justice to her misrepresentation, they displace our own subjectivities in the constellation of Pan Yuliang’s past life and her incarnation in our age as well as in the current exhibition, so as to introspect the gender bias and absence of female subjectivity in historical writing and mass media. Defying the usual autonomous zone of individual work and artist, all participants in the exhibition are hosts as well as guests of each other’s contribution. The research and the exhibition form a polyphonic orchestra that not only echoes Pan Yuliang’s unique trajectory between modern and traditional China, but also situates her constructed biography and artistic achievement within contemporary motives, detours and cosmos.

Pan Yuliang was born on June 14, 1895 in Yangzhou, China. In 1903, after having lost her parents, she was taken into the care of her uncle who sold her to a brothel in the Anhui province at age ten. This period in Pan Yuliang’s life has given rise to many interpretations that are more or less fictionalized. However what appears to be certain is that she met Pan Zanhua, a customs official close to the revolutionary movement. In 1913, she became the second wife of Pan Zanhua and adopted the name of Pan Shixiu – she took the name Pan Yuliang upon her first visit to France. In 1916, the couple settled in Shanghai where she learned to read and write. In 1917, she began her studies in painting with Hong Ye. In 1920, the Shanghai Academy of Arts allowed women to enrol and study and Pan Yuliang was one of the first students to attend. Upon the acceptance of women students, Pan Yuliang devoted herself to her studies until 1921. She then successfully applied for a scholarship with the Institut Franco-Chinois de Lyon, becoming the first few female artists to benefit from the program.

Upon her arrival to France, Yuliang attended courses at the École Nationale des Beaux-Arts of Lyon. In 1923, Yuliang moved to Paris where she studied at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts, notably in the studio of artist Lucien Simon and Pascal Dagnan-Bouveret. During her stay in Paris, she became friends with the local Chinese art community, including artists such as Xu Beihong, Zhang Daofan and Sanyu. She graduated from the Beaux-Arts in Paris in 1925 and received a prestigious scholarship to continue her studies at the Academy of Fine Arts in Rome, Italy where she trained in sculpture. After over three years in Rome, Pan Yuliang returned to Shanghai in 1928, and like the generation of artists who studied abroad, she played an important role in the circulation of modern art in China. Yuliang was appointed Professor of Western Art at the Academy of Arts in Shanghai and then at the National University of Nanjing, and significantly contributed to the creation and existence of many artistic associations. She exhibited her work on numerous occasions, yet despite her success, her work – which gives a predominant place to the female nude – and her past continued to cause many controversies and misunderstandings.

In 1937, Pan Yuliang left China for Paris to participate in the International Exhibition of Decorative Arts. She remained there until her death. It was initially the outbreak of World War II and then of the Cultural Revolution in China that seemed to have prevented her from returning to her native land – she attempted to return in 1956, but the diplomatic rupture between France and China forced her to leave her entire studio of production behind, which she refused to do.

She exhibited on a number of occasions, notably at the Salon d’Automne, Salon des Indépendants, Salon du Printemps, and was the subject of an exhibition at the Galerie d’Orsay in 1953. Despite this success, she struggled as a Chinese woman and more broadly as a woman in asserting herself as a qualified artist in the French capital, despite having realized an œuvre of unprecedented syncretism, of so-called Western techniques – such as oil painting – in combination with Chinese-like drawings in ink to create an intercontinental oeuvre that continues to challenge a simple classification today.

It is difficult today to retrace her life in France. Her recognition in Paris is owing mainly to contemporary Chinese circles – including the Association of Chinese Artists in France, which she took over as president in 1945 – and from the Cernuschi Museum, which collects antiques and Asian art. Just before her death in 1977, she organized the exhibition "Four Contemporary Chinese Artists" upon the invitation of Cernuschi Museum’s director Vadim Elisseeff. In 1952, Elisseeff had commissioned a bust of the former director of the deceased René Gousset Museum, whom Yuliang had known well. Yuliang also struggled in selling her works, several people who met her at the end of her life insisted on her very modest living conditions, her income being almost exclusively reserved to a small pension paid by the French State.

She died on July 22, 1977 in Paris at the age of 82. She told her friend Wang Shouyi on her deathbed that she wanted her works to be sent back to China. The contents of her workshop –more than 4000 works and personal belongings – was first transported to the Chinese Embassy in Paris before being sent to the Museum of Anhui Province in 1984 where they remain today.

About the exhibition

Curator: Nikita Yingqian Cai

Dates: 23 September – 19 November

Venue: Guangdong Times Museum

Artists: Theatre 44, Fang Lu, Hu Yun, Huang Jing Yuan, Qin Jin, Song Ta, Marc Vaux, Wang Zhibo, Mia Yu

Courtesy of the artists and Guangdong Times Museum, for further information please visit http://en.timesmuseum.org.