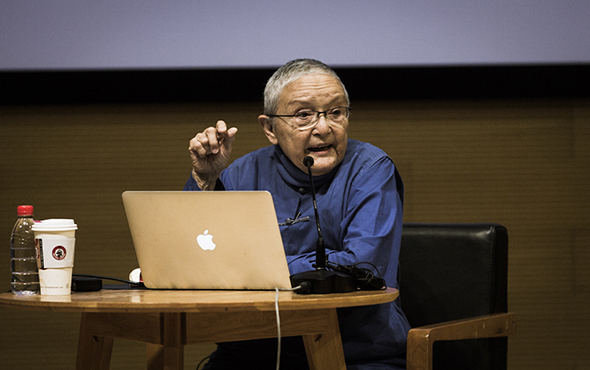

In 2012, the art historian Joan Stanley-Baker’s old thesis entitled “The Forgotten Authentic Pieces: Re-Identification of Wu Zhen’s Paintings and Calligraphy” was a new identification of the works of Wu Zhen, and she believed that there were only three and a half authentic pieces of Wu Zhen, triggering a new argument on the identification of calligraphy and painting. The follow-up publication of “Quotations of Paintings: Listen to Wang Jiqian Talking about the Brush & Ink of the Chinese Painting & Calligraphy” helps people to have a further understanding of the inventive scholar and her identification method that combines the style of the times, brush & ink, and supplements. On the evening of October 28, 2017, the “Artistic Symposium on Art History”, hosted by the Fanzhi Art & Education Fund and the CAFA Art Museum, was held at the auditorium of the CAFA Art Museum, and Joan Stanley-Baker gave a lecture entitled “Discussion on the Characteristics of Literati Paintings of the Yuan Dynasty”. The lecture was hosted by Cai Meng, Deputy Head of the Department of Curatorial Research of CAFA Art Museum. Zhang Zikang, Director of the CAFA Art Museum, introduced the speaker Joan Stanley-Baker and A’cheng who participated in the dialogue.

The identification process is divided into two steps by Joan Stanley-Baker: firstly, by dividing the history into periods, secondly identification. It is consistent with Xu Bangda’s “Style of the Times” and “Personal Style”, but the research process is different: first of all, it is necessary for Joan Stanley-Baker’s research to collect all the works under the name of the master, selecting the works of the respective style of the times, and then carefully examining them, in order to distinguish their characteristics, eventually, reviewing the documents of other masters in the same era to search for the narrative that is in line with characteristics.

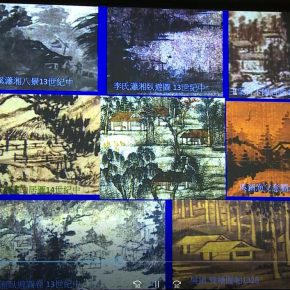

Division of the History into PeriodsDivision of the history into periods refers to selecting the works featured in the times, to verify and confirm the time of the production of a work. The style of the times is related to the structure and form (three perspectives etc.), and also related to the brush & ink action (wrinkle method, etc.). The works of each era has their own style of the times, if you want to find Wu Zhen’s authentic pieces, first of all you should find the style of the Yuan Dynasty. Firstly, Joan Stanley-Baker set out typical paintings of the Song Dynasty & Ming Dynasty, and the painting style of the Yuan Dynasty should be placed between the Southern Song Dynasty and the Ming Dynasty, and connecting both. Through this comparison, she found a feature: the later the time was, the more backwards the horizon moved and the clearer the wrinkle method was.

IdentificationFor the identification, the first method is to select and confirm the authentic work by the master from many pieces, which have the characteristics of the times, which are then called the works by the master. Joan Stanley-Baker searched for the landscape paintings in the style of the Yuan Dynasty, from more than 50 of Wu Zhen’s paintings, and summarized the features of the paintings. In addition, she read the prefaces & postscripts, poems, and records, etc. by the people living at the same time as Wu Zhen, who might have really seen the works of Wu Zhen, and these records revealed that Wu’s works were moist, lofty, running brush in a simple way, and the lines were not clear. Depending on these elements, three and a half paintings were declared to be authentic from the paintings of the characteristics of Wu Zhen in the style of the Yuan Dynasty. Joan Stanley-Baker cited the only authentic painting in the Southern Song Dynasty – Ma Lin’s “After a Rain in the Spring”, which revealed a natural silence, the handwritings of the paintings in the Ming Dynasty were noisy and urgent, while the authentic pieces by Wu Zhen, who inherited the style of the Southern Dynasty, really created such a quiet & restrained space, and the brush & ink also has consistency.

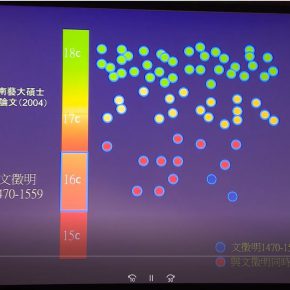

Secondly, it is a test method used to re-identify a well-known painting that was expected to be created in the Yuan Dynasty, such as the “Autumn Colors on the Ch'iao and Hua Mountains” by Zhao Mengfu, trying to find its true manufacturing era. Starting from the concept of the times, Joan Stanley-Baker used the scrolls that belong to Zhao Mengfu, to learn the “times” and “brush & ink”. If there are authentic pieces, depending on the arrangement of the inscriptions, considering the accumulations of composition and experience, the process & order of the personal aesthetic feeling that was gradually mature, we can find that “Autumn Colors on the Ch'iao and Hua Mountains” do not meet the process of the accumulation of experiences. Moreover, through the iterative sequence, one can clearly see that the brush & ink of the “Autumn Colors on the Ch'iao and Hua Mountains” is clear and delicate, so it was not finished in between the Southern Song Dynasty and the Yuan Dynasty; comparing it with the Japanese landscape paintings and the shapes of trees of the same period, it reveals a different artistic orientation. Starting from the analysis of two elements including “shapes of trees” and “brush & ink”, it is possible to trace the evolution sequence of the axis of the times, people can get the features of the leaves’ shapes in the middle of the 15th century, going through to the end of the 17th century: tree colors were increased, and they were bright, with diversified shapes of leaves; while the trunks were of many postures, gradually getting clearer. Therefore, Joan Stanley-Baker places “Autumn Colors on the Ch'iao and Hua Mountains” in between Jiajing and Wanli, or in 1590 when Xiang Yuanbian died.

The host Cai Meng said that Joan Stanley-Baker’s research emphasized an emotional experience. This occurred because she was able to examine the original pieces many times. Her methodology has three sources: firstly, she learned from Fang Wensuo in Princeton University, where she had training in structural analysis, and then she learned from Wang Jiqian in studying the appreciation of the brush & ink of the Chinese painting that depends on hand-eye experiences, as well as being trained with an attitude of appreciation that stressed the aesthetic value rather than a reputation in Japan. A’cheng had an evaluation that Joan Stanley-Baker finally established a new and complete method.

At the beginning of the lecture, Joan Stanley-Baker proposed a question: Emperor Qianlong wanted Wang Wei or Wang Xizhi’s works, but he had never seen one of them. So, why did he want a work created by a person that he did not know? Was it related to art? Was Wang Xizhi’s work created more than 1,000 years ago before he saw an original piece? In fact, the works of “Shi Qu Bao Ji” offer a reflection to the production of some works. The value of cultural heritage does not lie in the inscriptions, mountings, seals, prefaces & postscripts, praise or collection seals, and the essence of the work is its quality, meaning, value, and the work itself. Every piece of art has its own value, even though the painting is not authentic, it still has some artistic value. The purpose of identification was to clear the time of the artwork, and its relationship with the times.

A’cheng believed that the painting market was superstitious of the inscriptions and seals, which led to the ignorance of the quality of works. He affirmed the conclusion of Joan Stanley-Baker that, the final paintings were more than the ones at the beginning, so the use of “density” could exclude some works. However, in the Yandaixie Street, a child was trained to draw fake calligraphy & paintings from boyhood, so that he had a muscle group that was similar with the original painter, and thus it was also difficult to separate the authentic from the fake, from the perspective of the brush & ink. A’cheng proposed his view on the convergence between the Song and Yuan Dynasties, Song people put aside the chaos of the Sui & Tang Dynasties and the Five Dynasties, taking the continuation of civilization as their responsibility, which was reflected in the painting as “divinity”: the lofty, quiet and cosmic sense of the paintings in the Song Dynasty; when Song people painted landscapes, they painted the legitimacy and orthodoxy of the country of Song. This kind of “divinity” disappeared in the hierarchical system of the Yuan Dynasty. In the Song Dynasty, landscape paintings generally expressed the orthodoxy, which was only a personal inheritance and expression in the Yuan Dynasty. Once people mastered this ideology, they could make fake ones. “Autumn Colors on the Ch'iao and Hua Mountains” is one of the cases, Joan Stanley-Baker has proved was created after Dong Qichang, from the perspective of density, but it was not wrongly painted through legitimacy, the sharp Hua Mountain is a “celestial pole”. Joan Stanley-Baker and A’cheng offered different perspectives of identification from different perspectives, offering a new perspective and research vision to the scholars and students, resulting in undoubtedly a wonderful lecture.

Text by Wu Huixia, translated by Chen Peihua and edited by Sue/CAFA ART INFO

Photo and video by Yang Yanyuan, Hu Sichen/CAFA ART INFO