Landscape painting is not only the core of British visual art but also a great chapter in the Western history of art. The rise of Impressionism was influenced by British landscape painting to some extent. On 12 September 2018, “Landscapes of the Mind: Masterpieces from Tate Britain (1700-1980)” which was jointly organized by National Art Museum of China and Tate, London, was held at the National Art Museum of China. It is an exhibition of more than 70 pieces spanning 300 years that fully displays the development of British landscape painting.

Art historian Kenneth Clark once said: “Besides love, I am afraid that nothing can bring people more happiness than a good scenic painting does.” In the West, art has shown enthusiasm for landscape art since the Roman period, and many courtyard murals were represented on the theme of landscapes, but landscapes had appeared as foils for a long time, serving portraits or storylines, while it lacked an independent aesthetic value and gradually moved towards being independent in the late Renaissance. Under the influence of liberal capitalist democracy in the 17th century, the landscape painting began to become an independent painting category. Referring to the natural scenery depicted in the paintings, the “landscape” in England originated from the Netherlands.

British landscape painting originated from the geographical landscape paintings of the time, and was also influenced by Dutch landscape paintings. “Landscape with Rainbow, Henley-on-Thames” by Jan Siberechts which was created earlier than other pieces depicts the idyllic scenery of the Thames and a busy town, and it showcases the artist’s great interest in the natural world. Painter Jan Siberechts was a Dutch painter who came to England in the 1760s, and this piece also proves the connection between the early British landscape and the Dutch and Continental European landscapes. At the same time, some British landscape paintings also profoundly demonstrate the status of human beings in nature, for example, Joseph Wright’s work of “Sir Brooke Boothby” presents a figure leaning against a stream in the forest, and holding “Rousseau, Juge de Jean Jacques”, which also reflects Rousseau’s idea of people and nature living in harmony. Gainsborouh was a well-known portrait painter in the UK and one of the pioneers of British landscape painting. This exhibition presents his masterpiece “The Rev. John Chafy Playing the Violoncello in a Landscape”, and the character is in front of the landscape filled with a pastoral atmosphere. At the beginning of the exhibition, two major themes of British landscape art were revealed: depicting the scenery of a particular location and creating the ideal landscape of the mind.

The development of British landscape painting was always linked to the entire artistic style of Europe. French classicist painters Claude Lorraine and Nicolas Poussin had a great influence on the European continent in the 17th century. British tourists brought their works from France and Italy, and Richard Wilson was influenced by them during his travel in Italy. He shifted from portrait creation to landscape creation, and continued to draw Italian landscapes, as well as English villages, parks and the Mountains in Wales. He also laid the foundation for British landscape painting and was awarded the title of “Father of British Landscape Painting”. It showcases his work “Lake Avernus and the Island of Capri”, depicting a popular attraction in southern Italy. Wilson continued the classical style of Lorraine in this piece, with the tranquil lake and mountains, and the character activities that are embellishments of the landscape. It is Turner and Constable, who eradicated the Dutch and French models to create a model for British landscape painting and they were also the representatives of the top level of British landscape painting. Turner’s works are typical of “romantic” landscapes that challenge the balance and beauty of the classical landscape. He explored the sublime themes that blend with nature, including furious storms, as well as frightful billowing clouds and terrible waves. Turner was inspired by a real avalanche and created “The Fall of an Avalanche in the Grisons”, which deliberately depicted the rich texture and the veins of ices and rocks, conveying the noble side of nature and the devastating power that people fear. The landscape paintings by John Martin are also full of romantic power. “The Destruction of Pompei and Herculaneum” imaginatively showcases the tragic doomsday of the volcanic eruption that caused the destruction of the cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum, where volcanoes, black clouds, and tsunamis constitute a hellish scene.

Another master of the golden age of British landscape painting is Constable, whose work was different from Turner’s romanticism, as he chose to carefully observe and to depict the ordinary exquisiteness. He often sketched outdoors, and captured the constantly changing light which introduced different effects to the painting which offered a naturalistic depiction. “Chain Pier, Brighton” depicts a resort on the south coast of the UK, depicting the landscape along the beach, where the modern entertainment scene was in contrast with traditional fishing activities. Hidden in the real landscape, it expressed his concern about the demise of the pastoral scene, which was in accordance with his classic piece of “The Hay Wain”. Constable and other painters who sketched and created in nature directly influenced French Impressionism, while the Impressionist and a subsequent series of artistic schools infused new vitality into British landscape paintings. In the exhibition, Roderic O’Conor’s “Yellow Landscape” showcases that the artist squeezed pigments from tubes and directly drew on the canvas, which created a strong texture constituted by strips of bright colors on the canvas, and this style was undoubtedly influenced by Van Gogh.

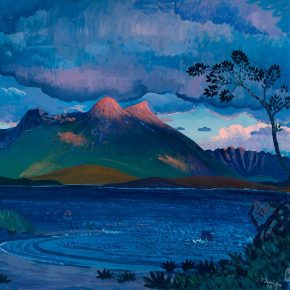

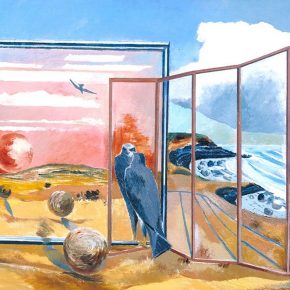

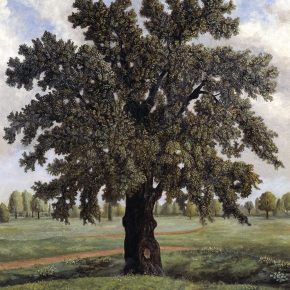

Since the beginning of the 20th century, British landscape painting has maintained a close interaction with a series of modern art movements. Landscapes of the Mind also presents the pluralistic state of British landscape paintings in two chapters. James Dickson Innes’ “Arenig, North Wales” highlighted in this exhibition was quickly finished by fluid brushstrokes, combining the accuracy of the terrain with unique and unnatural colors, which also reveals the influence of Henri Matisse’s Fauvism. Edward Wordsworth’s “Regalia” combines the still life in the foreground with the landscape, and also explores the combination of landscape painting and abstract painting. In his landscape paintings, Paul Nash combined surrealism with abstract art to create classic works that incorporate regional sensibility into unconscious symbolism. “Landscape from a Dream” presents an eagle that symbolizes the material world, looking in a mirror, in which a sphere symbolizes all aspects of the soul. This piece is obviously influenced by Ciorgio de Chirico of the metaphysical school. Peter Lanyon’s “Lost Mine” shows the original power of homeland, ocean and sky, and it was influenced by abstract expressionism in terms of expression. Mark Boyle’s conceptual piece “Holland Park Avenue Study” is a true copy of a part of the street of West London. He randomly selected this location from a map, and used resin, pigment and gravel on this street in the process of the creation. At the same time, some artists still insisted on the traditional theme being expressed in the traditional way. At last, it presents Stephen McKenna’s “An English Oak Tree” which reveals that he was inspired by the oaks previously created by many artists, in order to convey the monumental nature of this big tree.

There are only 70 works which is only a minor collection in the history of British landscape painting over 300 years, but these works come from different historical style nodes, and build a complete and clear development context of British landscape painting. It also explains the reason why landscape art has become the core expression of British visual imagination. It remains on view till November 6.

Text and photo by Zhang Wenzhi,translated by Chen Peihua and edited by Sue/CAFA ART INFO