Each man has his own destiny, but none is better than that of mankind.

—Albert Camus

I

Among the existing writings on the history of Chinese contemporary art, “overseas Chinese art” is an aspect easily forgotten by art historians. For years, artists who migrate overseas and create artwork there have not been a topic of discussion by theorists. Even artists who had some influence in China before moving abroad rarely become the research objective of theorists after they left China. Naturally, it has something to do with geographical considerations. With the deepening of global informatization and cultural exchanges, the flow and infiltration among people from different countries and social groups have gradually become a common phenomenon. As such, overseas Chinese artists have also started to travel frequently back to China for exhibitions and seminars. This special group now re-attracts the attention of critics.

“Overseas Chinese” usually refers to “Chinese living in other countries and regions other than mainland China, Hong Kong, Macao and Taiwan,” whose ancestors are Chinese but have a different nationality now. “Overseas Chinese artists” refer to a special and broad group, and we can’t use fixed criteria to judge and measure them because of different cultural contexts of the regions they live in, different individual experiences and backgrounds. Therefore, it’s not easy to investigate the “common traits” of the group. A more effective approach to study them is to present their “personality” of the state, experience and art practice between or among different cultures. The topic on HERE/ELSEWHERE: The Sample of Overseas Chinese Art has rich and complex cultural significance. As the curator Wang Huangsheng said, “from single cultural identity to multiple culture identities, from cultural psychology to the dual expression of cultural orientation, and from ideas of morality to a code of conduct and way of life, a new cultural ecosystem has formed, which also gives rise to art styles and phenomena with new cultural characters.”

Despite this, “overseas Chinese art” is still a relatively little heeded research field in China. Currently, only a few art galleries in coastal areas of Guangdong Province have conducted research in related academic topics. He Xiangning Art Museum has held three exhibitions on the theme of “overseas Chinese art.,” with a unique academic perspective and research depth each time. This theme integrates multi-disciplines, including anthropology, sociology, culture, history and others, and it is a very open and novel topic. A researcher with a broad vision, cross-cultural perspective and rich life experience can have a deeper understanding and grasp of this theme.

If we try to discuss “China” beyond the geographical factor, “overseas Chinese art” will become the most important visual model. Even though these artists are away from the living environment and cultural context of “native China,” the cultural memory of the Chinese civilization and the overall experience as a “root” play their roles everywhere. In foreign land, overseas Chinese artists outline the psychological and artistic picture of an “overseas China” in a creative way to varying degrees. After conflict, adaptation, and integration, they could create more powerful ways of remodeling and expression. If discussed from a broader perspective, their artistic creations should be regarded as part of the contemporary Chinese art ecosystem.

II

Holding such an exhibition in Shenzhen, a city which gathers new immigrants from China and around the world, is quite a contrast. For the general audience, especially for art students and practitioners who dream of studying abroad, it is a very attractive topic. What is the living condition of overseas Chinese artists? How do they solve problems in life and art creation in a foreign country? Does it differ from the general public perception? Most people don’t know how to answer these questions.

In a sense, He Xiangning Art Museum fills in a blank in the research of this subject. Since 2013, the museum has been continuously displaying and studying “overseas Chinese artists,” providing a pioneering platform for theoretical exchange and creative dialogue in this field. So far, He Xiangning Art Museum has held three exhibitions on overseas Chinese art. With the theme of LOCAL FUTURES, the first exhibition took young overseas Chinese artists as the research objective. It started the investigation from “identity”, the most important topic that overseas Chinese are unable to avoid. The multiplicity, marginality, and mobility of their identity are not necessarily negative. Rather, it can be regarded as a kind of vitality. Just as curator Feng Boyi puts it, “it forms a spatial tension in culture—a distance of attraction and repulsion,” showing a rich variety of visual culture value.

The second exhibition themed on DOUBLE VISION with the female artists group as the research objective. DOUBLE VISION means having “two pupils in the same eye”. The exhibition restored personal feelings in the past, present and future situations through their migration and life experience in different foreign lands, their multiple identities and creations. The exhibition did not deliberately emphasize the gender identity of “female artists,” but studied it as a kind of phenomenon. By comparing how the characteristics or factors were different from the Chinese native culture art, the exhibition made an attempt to find the inspiring values of the complex relationship between globalization and localization.

The third exhibition, entitled HERE/ELSEWHERE: The Sample of Overseas Chinese Art presents a dialogue across three generations. From the exhibition, we can see a linear migration history of how China’s artists have resettled overseas and created works there, and the overall characteristics of artists of three generations with different ages, backgrounds and experiences. HERE/ELSEWHERE is how curator Wang Huangsheng describes artists’ life experiences, mental state and identity. Starting from the identities and works by overseas Chinese artists, the exhibition selects 18 artists as representatives through social sampling methods, conducts in-depth surveys on the life and creation process of immigrants in the past 40 years, and forms a series of precious interviews and research texts.

One of the most prominent features of this exhibition is the key role of text, which involves survey and excavation, sampling and tracking, interview and dialogue, academic discussion and so on. To some extent, the text and the stories behind it have become the protagonists, while the artworks themselves have become footnotes. Built in 1990s, the partitioned space and ordinary floor height of He Xiangning Art Museum are not of much help in making overall observations of the exhibition to form a resonance. But with the case studies of artists, it does produce unexpected effects, and every relatively independent space can well show the individual expressions of the artists.

III

Apart from the group images, the individual narrations of this exhibition are a series of vivid stories of migration. HERE/ELSEWHERE is how curator Wang Huangsheng describes artists’ life experiences, mental state and identity. “Elsewhere” refers to the “special” identity and cultural background of overseas Chinese, and “here” refers to the individualized behavior in today’s globalization. The “Sampling” of artists has a sociological significance. Selecting overseas Chinese artists from three types of groups with different upbringings and ages is based on comprehensive considerations. It both includes artists with certain accomplishments in the history of Chinese contemporary art history, and new faces that the public is interested in but not yet familiar with. The so-called sampling is not random selection, but selective choices. Based on the emphasis on individual differences, the common problems reflected in the exhibition are what the exhibition is concerned about. These 18 artists also represent a large group of overseas Chinese artists from different aspects.

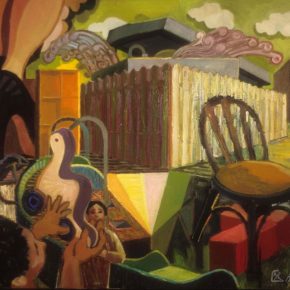

The three major sections of the exhibition focus on immigrant artists of three generations. The first part themed “Hidden Memory” focuses attention on artists who were born in the 1950s to the 1960s, received education in China, and migrated abroad in 1980s. They remember well the transformation of China’s social structure, development history and current reality. They may not really hope to come back home, but do feel discomfort and anxiety with the issue of identity living on foreign land. In a relatively relaxed environment, they constantly examine their experience and the fate of national history. Artist Xiao Tong is a typical representative. He is not familiar with the Chinese audience. He received literature training before going abroad, and only after he went to the United States did he truly follow his inner choice and systematically learn painting. His artistic creation still lingers in the past experience and memory of his father, and through art he constantly conducts self-confirmation and self-healing. His work Not Treat With Dinner (2012) recalls how his father stood at a dining table suffering criticism and denouncement, thus conveying a very abstract meaning.

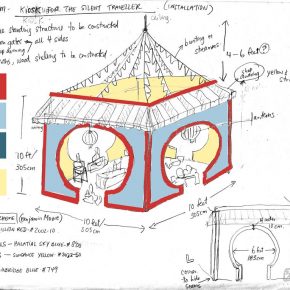

The second part named “Mixed Feelings” mainly focuses on the second-generation Chinese artists who have no domestic life experience, emigrated overseas at a very early age or were born overseas. The issue of identity gradually disappears for them, but the pursuit of the origin of their identity turns into “mixed feelings” in art. Unlike the first generation, this group does not choose to go abroad of their own initiative, and they even have a complex situation of “being unable to go back.” Therefore, most of them have a special imagination and a root-seeking psychology for Chinese culture. Just like the artist Tan Jiawen, who was born in Montreal but grew up in a Chinese family, Chinese culture is part of his cultural identity, but he is not really familiar with it and has not experienced it in real-life scenarios. So, he needs to keep exploring. His work Pavilion of the Dumb Walker (2018) recreates a “Chinese space” with lanterns, tea ware, porcelain and other ready-made products which possess Chinese elements and uses this to discuss how culture is read, explained and understood, and how culture influences our own way of being.

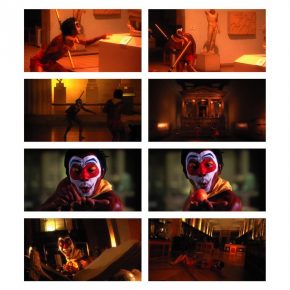

The third part named “Carnival of Walking” selects artists who were born in the 1980s in China, received art education abroad and work there. To a certain extent, it also reflects a trend of contemporary art—with the facilitation of transnational flows, a growing number of young artists have an international educational background, and most of them choose to stay abroad as long as conditions permit, or commute between their home country and foreign lands. Like the first generation, they were born in China, but the issue of identity is no longer a problem. They can freely use a variety of media and international language methods to show a wide range of interesting experiences, concepts and thoughts. They are often in a vague middle zone, connecting Chinese and Western experiences. Artist Yao Qingmei studied abroad after finishing college in China. She believes that only by changing the living environment can she know herself and stimulate her thinking. Her work has a clear context and features behavioral performances of both a social intervention nature and in the theatre space. Her work is presented in the form of images. Her work Judgment (2013) is combined with the rhetorical stance of the French revolution and the body language of the model of Peking operas of the Cultural Revolution in China. It criticizes three vending machines for their capitalism tendency, thus generating a strong sense of humor, absurdity and banter.

Although each exhibition takes a different group as its research object, identity has always been the most critical entry point in the three exhibitions on overseas Chinese art. However, an all-new fact is that the younger generation seems to be no longer limited to the identity issue. Due to the influence of their growth environment, the generation growing up in the 1990s seems to be naturally equipped with cross-cultural ideological preparations and a sense of identification. Therefore, the experience of living and studying abroad is no longer a prerequisite factor for cultural exchange and collision. Indeed, the globalization of information makes the world infinitely assimilated, with an identity flow and uncertainty happening at anytime and anywhere. After young artists who study abroad go beyond their label of identity, what should be vigilant is the crisis of “convergence” in outlook and expression brought by “globalization.” After all, only by maintaining cultural differences and diversity can cultural exchanges and dialogues be realized in the real sense.

Text (CN) by Zhu Li, (EN) edited by Sue/CAFA ART INFO

Photo courtesy of He Xiangning Art Museum

-290x290.jpg)