In the 1980s, China was confronted with a new start since the reform and opening up. At that time, diversified artistic thoughts flourished and avant-garde art forms emerged like a hurricane. In the field of young artists, there was an emotional trend for a reversal on “traditions,” which gradually became more intense and formed a climax between 1985 and 1986. Traditional Chinese art seemed to be an embarrassing position between the double attack of “surging” reforms and “menacing” Western cultural trends. Within this, ink art with profound Eastern traditions was the first to bear the brunt.

In the summer 1986, Yang Ling from Shaanxi Province planned an academic seminar on the topic of “Traditions of Chinese Paintings.” During the seminar, the organizers creatively juxtaposed two artists with sharp distinctive qualities in the ink and wash field – the public exhibition of Huang Qiuyuan and Gu Wenda’s internal exhibition were simultaneously held. The former is called “the last literati painter of the twentieth century” and he represents traditional Chinese painting; the latter is a representative avant-garde artist of the 1980s. Gu Wenda brought an installation work that combines ten giant ink paintings with performance art, “Drama of Two Culture Formats Merge,” which made Chinese artists feel the great destructive and advanced rebellious consciousness of ink painting. Zhou Yan, a critic who participated in the “85’ Art Trends” movement, pointed out that these two artists were included in the exhibition of contemporary art history by juxtaposing a “typical traditional watcher” with this traditional “contemporary challenger and interpreter,” to show the contemporary development of ink art, it confirms the “irreconcilable conflicts between the traditional and the modern, literati interest and discourse revolutions.”

Upon a retrospective on history, we find that this kind of “conflict” has never stopped.

I

Last week, “New Ink Art in China 1978-2018” curated by Zhang Xiaoling and Lu Hong was opened at the Beijing Minsheng Art Museum. Just like the two exhibitions “Upper Limit” and “Lower Limit” of the academic seminar of “Traditions of Chinese Paintings” in Shaanxi Province, this exhibition is divided into two parts: “New Chinese Painting” and “New Ink”. It has again juxtaposed two major types of ink forms with the same clue. According to the title of the exhibition, the works exhibited are limited from the beginning of the reform and opening up, systematically sorting out the dynamic history, diverse forms and rich features of the classics of Chinese ink art and the development of ink art during these four decades. Thus the exhibition intends to stimulate discussions and reflections on the developments of Chinese art over forty years.

The reference to “Chinese painting” does not seem to be strange to most Chinese people. This concept might be formed in the 1920s and corresponding to “Western Painting”, which is closely related to the epochal background: it is not just a form of painting endowed with the spirit of Chinese culture, it is also a manifestation of gradually awakening “national consciousness” of Chinese people caused by Western aggression after the Opium War. In the 1950s, under the advocacy by the government, a reforming movement on Chinese painting was carried out. This movement intended to carry out a “realistic” transformation of “old Chinese painting” and “traditional” painters. So far, the discussion about ink and wash has basically remained at the development stage from traditional literati to “realistic new Chinese painting.”

Since the reform and opening up in the new era, due to the development of the emancipation of ideology and the impacts of Western cultural thoughts, artists are more inclined to think and examine their own traditional culture. In the 1980s, there used to be a large-scale tendency of “Westernization” in Chinese society and the transformation of ideology became more and more feverish. In the 1990s, the trend of returning to the traditional was once again aroused. Thus, the dispute between “tradition” and “modernity” of ink paintings has become an unavoidable core clue in the history of modern Chinese art: Li Xiaoshan’s famous assertion in the Jiangsu Paintings in 1985, “Chinese painting has reached the end of the day,” which provoked an unprecedented discussion about the future of ink and wash. Exactly at the same time, Liu Guosong’s slogan of “revolution at center forward” also impacted on the traditional “ink and wash theory”; Lu Chen and Zhou Sicong revolutionized ink painting and advocated the theory of “Ink and Wash Composition” while teaching at the Central Academy of Fine Arts; in 1988, Li Xianting published “Southern Lines and Northern Wrinkle Methods” and proposed “the distinct management of ink and brush.” The “new literati painting” movement that was carried out thereafter was regarded as the tendency of “returning to tradition and regaining brush and ink”; In 1997, Wu Guanzhong proposed that “brush and ink are equal to zero” and Zhang Ding responded to “holding the bottom line of Chinese painting”...

In the new century, an increasing number of people are willing to use “ink and wash” instead of “Chinese painting.” If exploring the source, “ink” can be regarded as a richer and more extensive art form that grows and separates the attributes of Chinese painting. “Ink and wash” as a form of painting, has liberated a large number of artists who paint with ink and produced the concept of “new ink painting. ”The scope of new ink painting can be more general and it is not even limited to ink, brush, rice paper and other media, as long as the artist is seeking the traditional and Eastern meaning of ink and wash, it can be considered within the domain of new ink and wash.

II

For the Ink Painting Exhibition at Beijing Minsheng Art Museum, curator Zhang Xiaoling defined the exhibition as: “presenting the reforming and innovative history of Chinese ink and wash language”, “presenting the history of constant changes in contemporary art concepts”, “presenting the individual history of generations of artists”, the exhibition features 176 influential artists from 1978 to the present, including renowned artists such as Xu Beihong, Li Kuchan, Wu Zuoren, Li Keran, Lu Yanshao, Fang Zengxian and Huang Yongyu. There are also young and middle-aged artists who are active in the field of ink and wash.

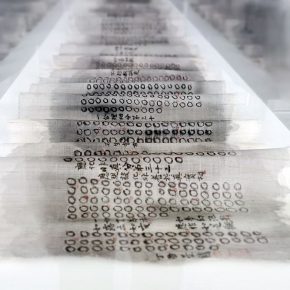

“This is an epic exhibition featuring new Chinese paintings.” “New Chinese Painting” takes realism as an art paradigm, and it serves the new art constitutions and forms in the modern ethnic constructions. It is worth mentioning that "New Chinese Painting" is a phrase that keeps pace with the trends and it does not change at the core with the altering situation. Zhang Xiaoling, Curator of the “New Chinese Painting” section, pointed out the “three transformations” that the work has undergone since the reform and opening up: from the national ideology to an individual position; from realism to freehand; from conformity to originality. The “construction of modern form” has always been the theme and appeal of the development of Chinese painting since modern and contemporary times, especially since the reform and opening up 40 years ago. Compared with “New Chinese Painting”, “New Ink” section of the exhibition emphasizes the modern and contemporary transformation of ink art. In the exhibition hall, we can also see some works that transcend the inherent themes of traditional ink painting or ink and wash treatments, such as Xu Bing’s “Background Story”, Gu Wenda’s “Mythos of Lost Dynasties Series”, Qiu Zhijie’s ink and wash images in “Copying Lanting Xu 1000 Times”. For the ink and wash artists included in this section, Curator Lu Hong pointed out: “On the one hand, they have contributed a lot to the critical absorption, transformation and reconstruction of Western modern art; and on the other hand, they have used the modern and contemporary consciousness to rediscover the modern and contemporary factors implied in traditional art, and all of these have important historical significance for promoting the modern and contemporary transformation of the ancient category of painting.” For this reason, “new ink painting” has gradually been accepted as a new artistic tradition and has become a part of history.

Coincidentally, a few days after the opening of the “New Ink Art in China 1978-2018” in Beijing Minsheng Art Museum, the National Art Museum of China also presented a special exhibition of ink and wash: “Reconfirm: The Future-Oriented Ink Art.” Compared with the former, the latter obviously emphasized more on the “future” ink art, reflecting on the historical situation of ink painting from the historical situation of “Western Application of Chinese Essence.” “I care more about the future development of ink art, not the past.” Wei Xiangqi, Curator of the exhibition, talked about the core of this ink painting exhibition at the National Art Museum of China. “When China and the West cease to deliberately look for this difference, we enter an historical process of authentic contemporary ink painting.” “The dialectical unity of essence and appearance” is a philosophical proposition put forward by Cheng Yi during the Northern Song Dynasty and the exhibition tries to point out that when an artist emphasizes his intuition, he puts aside the binary barrier in his innermost thoughts. When there is no difference in the essence and appearance, you can directly point straight to the heart and reach the artistic origin.

Ink art has a history of more than 2,000 years in China. Exploring ink and wash art in the cultural context of China, will this limit the ink and wash to a fixed category which thus cannot become an artistic language shared by human mankind? Some scholars believe that “brush and ink” is a representative feature that is different from other painting languages across the globe. “Ink and wash structure” is the soul and lifeblood of Chinese painting. Some scholars also disagreed with this. They believe that over-emphasis on the “brush and ink” form is one of the reasons that ink and wash cannot become the common language of the world like oil painting. Weakening the use of brushes, emphasizing ink and media itself are the real method for ink and wash exploration in the era of globalization.

III

We can see that the bigger problem confronting Chinese ink painting in the 1980s was how to preserve its own style under the crisis of impact from Western cultural thoughts. In the 1990s, discussions around ink painting focused more on how to acquire identity in contemporary and global perspectives.

Regarding the development of ink and wash, the critic Chen Xiaoxin put forward the “four-step” theory of ink and wash changes. In his view, the first step in the destiny of ink and wash is to “pick up the brush and ink” or “return to the brush and ink.” The most typical example is “new literati painting,” such as Wang Mengqi, Chang Jin, Zhu Xinjian, Li Laoshi and so on. In the modern ink painting camp, there are also some artists who are adept at using both “brush” and “ink” and they complement each other, such as Li Xiaoxuan, Li Jin, Xu Lei, Liu Qinghe, etc.; the second step is “separate management of brush and ink (including colors),” separate management here refers to: an artist that can manage brush, ink and colors according to his own preference, and more importantly, the needs of expression can be separated to play roles. The third step is “generalized brush and ink”, or “none” of brush and ink, that is, there is no traditional sense of ink, but “making an issue of”, such as Cai Guangbin’s ink video, Hu Youben’s sticker landscape, Hong Yao’s “origami” works, Qiu Zhijie, Wang Muchun’s “washing ink”, etc.; the fourth step “brush and ink return to zero” or “decay of ink and wash,” the traditional brush and ink enters into the dying process of “phoenix nirvana”, began to diffuse, reincarnate, resurface, there are typical examples such as Gu Wenda’s “The Great Wall”, Yang Jiecang’s “Thousand Tiers of Ink” and so on. From this, the ink paintings with a history of nearly a thousand years in China have been brought into a contemporary context of equal exchange with the international community.

On the contemporary appeal stage of ink and wash, the art of ink and wash is “completely integrated into the multimedia and diversified contemporary art family”, and the relationship between ink painting and tradition has become a kind of luminous “ink spirit” and “Chinese wisdom.” Therefore, we will find some non-traditional ink and wash works which are unlike ink and wash from a traditional perspective. For example, Xu Bing’s “Background Story”: The traditional landscape paintings that are familiar to the Chinese audience are presented in front but when you turn to the back of the work, you will find that the “traditional landscape” is made up of trivial objects such as dried plants, branches, hemp, and even garbage bags, they are formed by adjusting the subtle relationship between light and shadow in space. This is not the ink painting in the traditional sense, and let alone the ink media is not used. This is “brush and ink returning to zero.”

In the contemporary era, both the traditional “New Chinese Painting” and the “New Ink Painting”, are confronted with greater challenges and problems. “If the most embarrassing part that traditional ink discourse come across in modern life, lies in the disappearance of its context and lack of words,” said the critic Pi Daojian. In the article, he pointed out: “Thus, striving to complete its own modern and contemporary transformation to pay attention to and express the current ink and wash discourse, it faces precisely this discourse with Western knowledge as its background, as well as the colonial cultural mentality immersed in the illusory self-comfort that is in line with world culture.” Thus, even if it is the prospect of “future ink”, we should adjust the self-examination on our own traditional culture and stay alert to the “international trap” of Western accessories.

There is no doubt that ink and wash is an important cultural resource for our participation in international dialogue today. Throughout the 40 years of reform and opening up, ink and wash art has never stopped exploring the epochal trends. Although the topics of ink “breakthrough and return” are already commonplace, examining the essence from the historical nodes of scattered disputes: going out is to get back to the original point, and to return to the original point is to go out. This kind of progress and appeal like the Mobius Strip, there is no starting point but a steady stream of progress. It is the most basic logic in the development of ink painting from the 20th century through to now.

Text by Lin Jiabin, translated and edited by Sue/CAFA ART INFO

Photo Courtesy of Beijing Minsheng Art Museum and the National Art Museum of China