Uncertain Existence (2009) is an art installation from ten years ago by Chen Qi. It symbolizes the artistic motif of Chen Qi’s ongoing works and the future direction of his new art pieces. Being a leader and representative of Chinese woodblock printmakers, Chen Qi has maintained a strong sense of creativity while being highly sensitive to current circumstances and constantly adopts new ideas and methods in his artistic creations. From November 15th, 2018 to March 20th, 2019, Chen Qi recapped on his artistic practices in the past at the Deji Art Museum in Nanjing. The exhibition, his largest solo exhibition, is divided into nine sections. Within the space that is more than 2000 square meters, the exhibition does not only contain over 200 prints and installations created by Chen Qi from 1983 to 2018 but it also presents the latest group of experimental works. The exhibition showcases a past of Chen Qi as a farewell ceremony as well as a foreshadowing, aiming for a new departure.

Zhu Li: Mr. Chen, your solo exhibition recently at the Deji Art Museum in Nanjing, The Physics of “Chen Qi”—Experimenting With Curation and Comprehension was curated by Mr. Qiu Zhijie. Featured a Qiu style, what is your experience of working with Qiu who is an artist-curator?

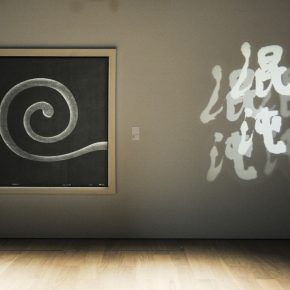

Chen Qi: For a curator, an exhibition should offer a different lens from other people. However, it doesn’t have to provide a different form; rather, it excavates a type of “truth” through the phenomena. This is the first question he considered before his curation. Qiu thinks that the works of Chen Qi have been defined. Hence, the key for this curation is to explore a different Chen Qi from the already fixed categories. Qiu said:“You are not an ‘elegant controller’ as concluded by others, but a ‘crazy experimenter’.”

Zhu Li: Mr. Qiu’s organization is indeed the highlight of this exhibition. At the same time, he presents his curatorial ideas and ways of thinking like a piece of artwork, which also guides the audience to follow his rhythm, understanding, and presentation. The exhibition itself can affect the audience’s own judgment to a certain extent. What do you think of it?

Chen Qi: My working experience with Mr. Qiu is quite interesting. In the beginning, I said: “Since you are the one curating, all I can do is to offer what you want.” His curation is a kind of creation, and I cooperate with his curation. I prefer to be a beholder rather than a participant throughout this process. I think a curator needs a strong knowledge framework and to be familiar with the works of the artists. Qiu has seen all my articles and my works which are deeply embedded in his mind. He will then re-classify the works within a framework in their totality and deconstruct them again.

Actually, Qiu was very comfortable when organizing the exhibition. The exhibition is an extra surprise for people and me. For example, in the final panel “Rumination”, there are works done in the 1980s when I was still an undergraduate as well as some works completed in 2018 that are considered the latest experimental works. When these works are displayed face to face on the two walls and in contrast with each other, they formulate a dialogue talking and reflecting each other. Even though the gap is more than 30 years, their inner spirits are still the same. There was a clue 30 years ago that reflects what I have become today.

Zhu Li: You just mentioned that your inner spirit is throughout your artistic life. Considering the entire artworks you’ve made, what is your biggest feature of your artistic character? What have you always insisted on, and what is your consistent inner spirit?

Chen Qi: I think the main thread is to always look for myself. Find yourself, ask the meaning of yourself, the meaning of existence, and the meaning of life. That is how everything is reflected in my artworks.

Later, I realized that the sights of some other artists are aimed towards their external influences, such as observing and intervening in their social matrix. Instead, I am moving more towards an inward perspective because I am always studying myself when making art. This is not a narrow understanding of the “self,” but rather, a person— an investigation of the “Person” with a capital P. Therefore, the painted subject matter or content becomes less important. Those are just topics, and the core is not to draw a tree or to depict a landscape. Instead, it represents the inner “human,” the existence of its individual consciousness, and the deeper level of its existence. This is its meaning and value that eternalizes itself.

Zhu Li: Mr. Qiu thinks that you have developed two paralleling characters—“an elegant controller” and “a crazy experimenter,” but I have noticed that your artistic practice is a linear system, starting from the unconscious experiment to a precise control of artistic creations, and then begin all over again after your exhibition at the National Museum of China with some experiments to find other possibilities. This is a natural process rather than an organized plan. Your elegant and exquisite preferences and control over the picture plane in the creative process, from my perspective, perhaps is partially based on your professional habits or personality. What do you think?

Chen Qi: I think there are parallel developments as well as intersections. Not all works are elegant and poetic, or completely cozy and violent—they are madness under control. This is based on my claim on the quality of the work. I can’t endure my work being shoddy. In other words, it should be substantial in its spirit and thought, and possess an ontological texture. In my work, the ontological aspect refers to the texture of the woodblock prints. In order to pursue it, I actually developed a sense of conceptual thinking that features a breakthrough in the limited understanding of the ontological woodblock prints.

It is similar to the world of science. If we cannot find breakthroughs in the theoretical aspects, it is impossible to produce a revolutionary change in science and technology. Therefore, the revolutionary change can be based on the breakthrough of the most fundamental theoretical research, which is what I have been thinking about: how prints have made breakthroughs in the most basic aspect with its own ontology.

Zhu Li: Yes, this is also one of your characteristics. In addition to the printmaking practice, you’ve also considered many problems with the printmaking theories. You have been working on theoretical research, and what do you think is the significance of printmaking in our current era?

Chen Qi: In my opinion, printmaking is a media art of the past. It is plural and produced by printing. The purpose of printing reproductions is to spread information. Printmaking has been the most effective medium for image transmission prior to the invention of the camera. Today, this technology clearly does not have an advantage. Hence, nowadays I have to consider what the meaning of multiple productions is? Of course, an artist, through the reproductions of his works, can attract more intentions through collecting and appreciating, but the original still possesses a certain value. In the perspective of image and information dissemination, it has no advantage, hence what is the core competitiveness of printmaking in this era? I have always come up with the idea that printmaking should be distanced from paintings.

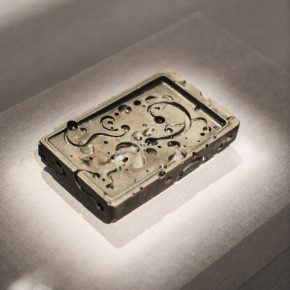

Its distance with the painting has a two fold meaning. In the past, printmaking was used as the plural to spread images, and its original version was produced by drawing. Therefore, the printing effect was close to its manual draft. This logic is different and unnecessary today, and this is why I said that prints and paintings should be separated from each other. The printed marks produced by the printing plates are unique to this technique and are not available in other types of medium. In the past, the printing plate was a bridge to restore the image, or an intermediate medium leads us to see the restored image and becomes a hidden image on the printing plate. What I have to do today is to bring the printing plate from the background to the front. The first experimental thing I did is to use the printing plate of the past 20 or 30 years to deconstruct and reconstruct its picture plane, and this offers a new meaning to the work.

In addition to the purposeful imprints, the second fold meaning is pluralization. The expansion of the plural is what I called a non-mechanical plural. It means that when we make a print, we might replicate twenty or fifty—a plural. This type of plural mentioned today is actually called non-mechanical plural. It can be printed on ten or twenty sheets, but within these ten or twenty sheets, each one of them can be different and therefore have new changes. This is a type of representation of the non-mechanical plural. A statement hence exists in the picture, and you can use this plate to print the plural of the image visible for this exhibition. That is to say, on a single piece of paper, the original printing plate can be used to perform a plural printing, and then in this way, the plural printing actually possesses another meaning. It is different from the past because the work shifts from a picture to an alternative experiment.

Zhu Li: Why did you choose the classic images that you have done in the past as your new experimental art, such as Ming dynasty furniture, lotus flowers, and bergamot, etc..Why not try something crazier? Do you intend to create a dissolution?

Chen Qi: During the printing production, the wrong version is always considered as a wasted product, as it resembles a performance of poor technology. But the classic works that have been deeply rooted in people’s hearts are the same superb techniques talked about by people all the time....Hence, no one will question my technique. Reusing these classic works is a way to carry out the experiment from the complex non-mechanical plural with a wrong version and gives people a sense of rationality. In fact, it is a challenge for the classics. I used to build classics, but now I try to deconstruct the original one and to carry out a revolutionary reconstruction.

Zhu Li: This exhibition acted as a conclusive collection and emphasized itself as an experiment. What would the direction and fate of this new ongoing batch of experimental works be?

Chen Qi: My interest is not in how many paintings I have to make but through this way of breaking through to rethink the basic theory of printmaking. However, this is only a method rather than my ultimate goal. I want to use this kind of experiment in future creations which allows me to open my hands with more freedom. This is important for me. I am not satisfied with merely using the past plates to print different new works. At the same time, I cannot endure this repetition following the approach of doing things in the past. I will definitely create brand new things.

Zhu Li: The latest work of this exhibition is the “Puncture the Ice Lake” which was just taken out during the exhibition. Is there any clue as to your new work from this piece?

Chen Qi: Definitely. I think from the day of the exhibition, I have already said goodbye to the past Chen Qi. In other words, the later works are not the same as the previous works, such as the work similar to “the lake piercing the ice”. The lake that pierces the ice is actually a reduction. I express an idea, but during the expression, my works become full of uncertainty. I am very interested in uncertainty. In fact, in this uncertain creative process, the artist is always facing choices and challenges, and I like this feeling.

Zhu Li: You have previously created the largest print in China — “Generation and Dispersion of 2012”. At this time, you extended on the basis of the original. What was the reason for making this work so big? Other than technical and visual breakthroughs, do you have other considerations?

Chen Qi: The total length of “Generation and Dispersion of 2012” is 42 meters with seven 4 meters units in the middle. The left and right are copied once, and each copy is made with the original plates. There are 7 groups of non-mechanical reproduction either from the left to the middle or from the middle to the right.

This piece has a total of 8 plates. It consists of 7 units and 7 parts in which 7 pieces are put together. Hence, in the first printed version, I printed one plate, in the second one, I printed two plates, and in the third one, I printed three plates. From one to seven, the artworks become a process of a generation. When it came to the 8th plate, it just happened to be connected to another unit. In the same way, when it comes to the other side, it is then completed. The size of the work is not purposeful; instead, it reveals the law of a thing—from generation to its extreme and its extinction. In fact, it is the process of life and death and a process from the past to the future.

Zhu Li: You have so many series of works, and each series have alternative changes. Thus, when will you formally decide to end a series, what’s the node of it?

Chen Qi: Actually, my work contains a strong sense of being part of a series because I always feel that I have more to express. The analysis of one thing contains merely one perspective, and it is not enough. It may be necessary to carry out an interpretation from many perspectives, such as one as macroscopic, microscopic, descriptive, and probably qualitative. For instance, I started to work on the topic of water from 2003 to today, but nowadays that water is not the water at that time. It becomes a topic rather than a theme. When you see the works on water later, they are more abstract and even loses the likeness of water.

In fact, through the experience of life, I rethink about the “existence and the meaning of existence” and continue to make interpretations. The process of interpretation is actually through a theme. Of course, when you feel that you are always repeating your work then stop and look for another topic.

Zhu Li: Mr. Qiu has used the word “cautious” many times in his article. He describes that you smile cautiously, choose carefully, and cautiously. What do you think of your authentic character? Do you think this word fully describes your characteristics?

Chen Qi: Firstly, I am in awe of everything. Second, I have an absolute equal awareness about everything. I never feel that I have a feeling of being at the top, and of course, I never fear the supreme. Therefore, a cautious smile is not to be wary of others but to maintain modesty.

Zhu Li: Painting has entered the era of algorithms, but in fact, printmaking was there earlier. Digital prints have long used electronic technology. In such a digital age, painting becomes more and more closely connected with technology. How can we continue to do this in this dimension? When the boundaries between art and technology become greater and more blurred, then what is the core thing we should grasp in our lives?

Chen Qi: The literal understanding will be delayed. The algorithm is actually based on data, there are all kinds of possibilities, so what kind of result do you hope to get? I can practice with different algorithms. Hence, an algorithm in the painting, from my perspective, means that painting has unlimited possibilities rather than that of a single setting.

When art or painting becomes more and more closely connected with technology, or when their boundaries are increasingly blurred, what would be the core thing we should grasp? Human nature. As we often discuss nowadays, when artificial intelligent robots gain a powerful deep self-learning, people’s mastery of knowledge like operational skills probably cannot proceed with robots. Will robots eliminate humans? This is a topic we often discuss. I think it will not because people have human nature on a spiritual level, and this will never be replaced in technology.

Zhu Li: Over the past years, your artistic subject and core concepts have always been in the dimension and scope of printmaking. It can be said that you have been defending the discipline of printmaking. What makes you so persistent?

Chen Qi: It is based on a very simple belief—how to manifest the vitality of a thing? There must be someone to do it, and there must be a convincing work. This is what I think is the most valuable thing. If there is no practice and no works, all other things will return to nothingness.

I feel that I am more and more interested in artistic practice now, and I become open and free. Currently, for me, there is no failure, and anything can be done. I am fully open and not limited by the media. Of course, I have already been familiar with the attributes of the media, however it would need to make sense. As with the experimental works I have completed, I have never thought that many people like it very much.

Recently, some works are more straightforward, and people often ask, why do you make such works? What I am pursuing is a poetic meaning of the writing in a traditional sense, similar to traditional literati painters who emphasize painting to be a type of calligraphy when painting landscapes. At that time, there is no such thing as printmaking and all these are well-planned pictures without a deep-seated behavioral factor.

I tried to achieve a sense of writing in the prints with my own body which possesses the beauty of the prints. This trace is by no means an effect of the direct drawing. Instead, it contains rich information comprehensively presented by the artist’s mind, behavior and the medium specialism of wooden materials, as if you are giving a five-minute speech that is completed with your extreme body flow because it is what you have learned all your life, including your speed, passion, and the composition of the entire picture. Why? After five minutes, the ink had dried on the board and cannot be printed again. How can you reprint it on paper and displace it entirely? Everything has to be done in such a short time and it is a challenge to your mind and skill as a whole.

Text by Zhu Li, translated by Y. A. Ois and edited by Sue/CAFA ART INFO

Photo Courtesy of the Artist and Organizer