The heaviest of burdens is therefore simultaneously an image of life's most intense fulfillment.

The heavier the burden is, the closer our lives come to the earth,

the more real and truthful they become.

Conversely, the absolute absence of a burden causes man to be lighter than air, to soar into the heights, take leave of the earth and his earthly being, and become only half real, his movements as free as they are insignificant.

What then shall we choose? Weight or lightness?

– Milan Kundera [1]

What is the choice between weight and lightness? This question Kundera proposed seems to have never been answered. Everyone comprehends the significance of Lightness and Heaviness differently. Within these two notions’ obscure meanings, the complicated clues produce the opportunity for narrative, while the inspiration originates from deep in life and erupts.

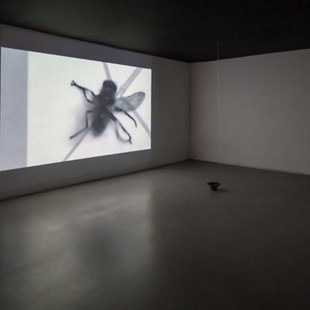

Artist Geng Xue’s latest solo exhibition “The Lightness of Being” showcases her capture and interpretation regarding relevant topics. Curated by Alia Lin and Professor Shao Yiyang as its academic director, the exhibition recently commenced at Zhuzhong Art Museum. By focusing on eight groups of Geng Xue’s recent works—the Name of Gold, Socrates’ Square, the Fly, a Childhood Fable, the Poetry of Michelangelo, Two Mounds, the Piping of Heaven, and the Tape of Freedom, the exhibition presents the artist’s personal narrative style. Various installations, sculptures, videos and sketches within the exhibition seem to construct a mythical approach to speech and a poetic feature of art creation.

Quoted from Kundera’s The Unbearable Lightness of Being, the exhibition title “The Lightness of Being” questions the duality of lightness and heaviness as well as their inverted relationship. Geng Xue reflects on the way to convey the power of life, the multiple layers of meaning regarding violence, fragility and void. Professor Xu Bing, Geng Xue’s supervisor, once commented that a special concept of the artist’s “hand” was conveyed through Geng Xue’s work.[2]

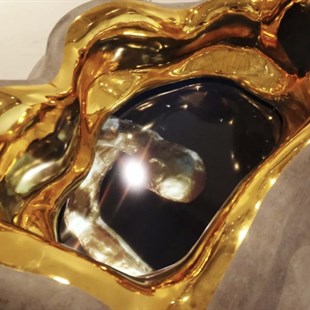

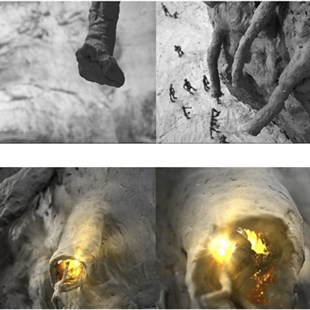

The dual-display video The Name of Gold (2019) created by Geng Xue presents a black and white world in which the gold is used as a finishing touch. The artist created characters with clay to construct an ecosystem. All the characters in the film serve a monolith and they even sacrifice their own children to the monolith. Everything is tied to this immeasurable monolith. What is inside seems to be a circuit board that flashes digital time, absorbing “sacrifice” in every direction.

“The Name of Gold”

Geng Xue once mentioned that the name of this work was inspired by the Italian author Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose. “The rose of old remains only in its name; we possess naked names.” This intellectual mystery includes a number of topics about church, religion and theology. Meanwhile, it presents Eco’s research on semiology and linguistics among others, which is reflected through the discussion of belief and rationality, desire and reality etc.

In Geng Xue’s The Name of Gold, the story elements such as the cave, stairs, births, deaths, children, the elderly, the heart of the golden blood, together with the compact plots imply a great deal of symbolic metaphors - some inquiry into the origin of life, while others imply the human existence rules and reflects on the phenomenon of the times.

In terms of her artistic approach, gold symbolizes nobility, glory and brilliance, while black and white highlights the texture of the earth. Gold, as a floating “lie,” represents an idealized illusion which envelops people’s supreme imagination. The strong contrast between the earth and the circuit board among others, reveals the comparison between primitive stuff and new technology as well as purity and complexity.

Born with an invisible “chain,” everyone circles between life’s lightness and heaviness and obeys the huge “common ideal.” Through this deep impression, Geng Xue inscribes a “gold imprint” in the hearts of audiences. It might evoke the review of the monolith and the rethinking of repetitive behavior in different people’s hearts. These thoughts cannot be hidden or escaped from. What is in between the mediation of lightness and heaviness can only be “The Name of Gold.”

“The Poetry of Life, A Childhood Fable”

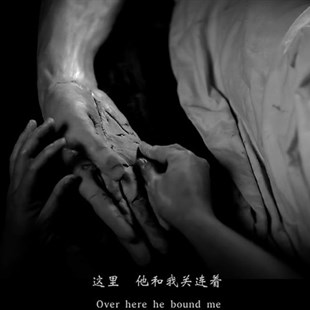

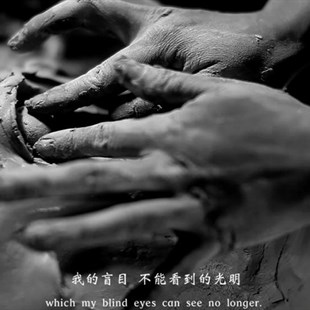

In Geng Xue’s work, a long-lasting pursuit of idealization and a mysterious power beyond reality, as well as a romantic purity can be perceived. The work The Poetry of Michelangelo (2015) mixed video, sculpture and performance. In the video, she adopts the behavioral process of sculpture teaching and uses clay modeling as a script. She builds clay blocks, shapes the head, arms, abdomen, eyes and noses of the sculpture. By doing so, the shape of the clay figure was gradually realized. Then she divides the sculpture into several sections, revealing the cruel beauty and a cycle of redemption.

From the artist’s point of view, the lifeless clay figure is full of vitality. The video shows the interaction between Geng Xue and the figure. Geng Xue said, “When I was making the eyes, he would open his eyes staring at me. When I was making the hands, he would grab me with his own hands. When it was nearly finished, I blew the air into his mouth. Hence, his chest started to rise and fall and he began to breathe.”[3] This love poetry ends up with “disintegration,” while the whole process is like a “surgery” with proficient skill and being close to the real; however, the dramatic process is full of a fantastic magical effect.

The narration of the film is Michelangelo’s sonnets, which is powerful and splendid,

"Your eyes of wisdom enlighten my blindness. Your feet help me to bear the burden that my disabled feet can’t bear. Your spirit brings me to heaven. My will is contained in your will, my thoughts are formed in your heart, my words are revealed in your breath."[4]

The entire process of creation is full and rich in terms of the content of the storyline, the behavior process and the method of recording. Meanwhile, the emotion is authentic yet with hidden violence and conflicts. Geng Xue utilizes her own body and the object, together with her expression and behavioral process, to present the discussion concerning life and faith, death and love as well as soul and body.

A Children Fable (2018) is also an installation mixing sculpture and video. This creation originated from a thorough cleanup of the Department of Sculpture. In accordance with Geng Xue’s memory, heavy objects were thrown out one by one by students. Due to the specificity of the space, those objects were hitting the ground and constantly creating a reverberation, which was very much like the sound of explosions and gunshots. Geng Xue was deeply impressed by that. She felt that the young students’ throwing actions were as fierce as the characters in the news on war.

Inspired by this experience, Geng Xue reconstructed these two feelings in her memory, namely, the cleanup scene and the film clips in relation to children and war created in the 1960s to 1970s. Therefore, messy visual images and sound effects were realized and placed in the center of the installation. The waste “art teaching materials” are collected and made into child-sized figures, which feature a primitive, simple and vivid energy. However, what is behind the child-like images are the violent, radical fragments and sounds. Although the contrast enables the work to be full of conflicting effects, audiences can still perceive the artist’s emotional care and reflection on humanity.

“Double Praise: Powerful but Fragile”

Geng Xue’s works dig into the complicated and subtle feelings about life and ideals. For example, the film shot by iPhone, The Fly (2018) records a series of struggling sounds made by the fly after being trapped. The sound’s volume and frequency from such a small body are astonishing, as Geng Xue said, “It turns the dying inset into a complex musical instrument.” The whole process reflects a fragile life’s inquiry into pain and death.

In Socrates’ Square (2017), fragile glass and white porcelain are used for organs that symbolize the individual life and collective will, expressing fragility and fear. The sound installation The Piping of Heaven (2018) initiated by master craftsmen in Jingdezhen where Geng Xue encountered. It collects sounds including mountains and rivers, a porcelain making workshop, and craftsmen of various divisions at work. The sounds are transmitted from eight different locations to the 100-meter-long tunnel kiln. The artist intends to connect the sound of the whole city and the era, thus to evoke thoughts about individual experience and living memories.

As Professor Shao Yiyang, the academic director of this exhibition, commented that in Geng Xue’s works, we can see a form of art that is open-minded and general. “She has never restrained herself within certain media. Starting from the most basic materials, clay and fire, as well as the origin of life, sex and death, she freely collages all kinds of materials and images, employs multiple media including video, audio and image and crosses the boundaries between ceramics, sculpture, video and body art, as well as numerous doctrines such as romanticism, realism and modernism. She allows the audience to find ‘strangeness’ in the ‘familiar’ narration, the ‘complexity’ in the ‘simple’ form and the ‘difference’ in the ‘consistency’”.[5]

Reference:

[1] Milan Kundera, The Unbearable Lightness of Being, trans. Michael Henry Heim (London: Faber & Faber, 2000), P5.

[2] - [5] Exhibition text, Zhuzhong Art Museum.

Text by Zhang Yizhi

Translated by Emily Weimeng Zhou

Edited by Sue/CAFA ART INFO

Photo courtesy of the artist and the organizer.