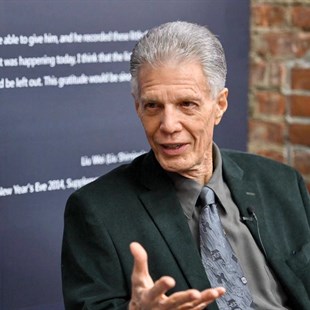

As a writer, artist, critic and art historian, Professor Robert C. Morgan has a background in the history and aesthetics of both Western and Asian art. He also works as a curator and educator focusing on international artists and exhibitions. As an art critic, Morgan currently writes for The Brooklyn Rail and Whitehot Magazine in New York and, from 2014 – 19, was the New York Editor for Asian Art News. In 1999, he was given the Arcale award in Salamance (Spain) for his work as an International Art Critic.

On the occasion of the exhibition “Departure and Return: Liu Shiming’s Sculpture” at the Asian Art Center New York, Professor Morgan was invited to attend the opening reception. Two weeks following, CAFA ART INFO arranged an interview in which Professor Morgan spoke about Liu’s sculpture, focusing on the artist’s spiritual understanding and aesthetic dimensions. Accompanying Professor Morgan, Liu Wei, the son of Liu Shiming, contributed his special memories and insights.

Section One: Interview with Professor Robert C. Morgan

The beginning of the interview between Professor Morgan and CAFA ART INFO started with a discussion of Liu Shiming’s sculptural language. This included comments on the technique referred to as “kneading.” This further developed into comments related to the work’s significance relative to Liu Shiming’s exhibition in the U.S. that included the Professor Morgan’s interest in the artist’s philosophy as an artist.

CAFA ART INFO: Good Morning, Professor Morgan. Thank you for your time. I believe you had the opportunity to view the exhibition of Liu Shiming two weeks ago. Was this the first occasion for you to experience his art directly?

Morgan: Yes, I received an invitation to come here (Asian Art Center New York) for the exhibition opening. I was not sure who gave them my name, but it was a generous invitation. I read about Liu Shiming and that interested me. So I decided to come.

CAFA ART INFO: So after viewing Mr. Liu Shiming’s exhibition, how do you understand and comment on his works in terms of his sculptural language? I learned that you have a sculptural background.

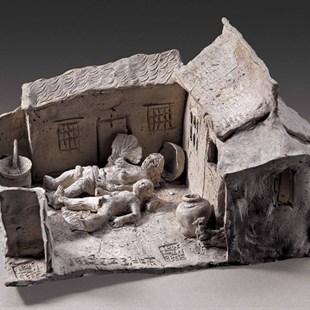

Morgan: Yes, I do. I received my MFA in Sculpture. I have been a Contributing Editor to Sculpture Magazine, and now I am the New York editor for World Sculpture News. Regarding Liu Shiming’s sculpture from a historical, cultural, and sociological perspective, I was interested in the fact that much of the work was done during the 1960s and 70s. This was a subject I wanted to explore further. I was interested in the forms and the subject matter he was using. I think these were really within the context of Chinese folk art.

I am interested in the survival of Chinese folk art. I see the previous time in which he worked as the beginning of a rejuvenation of the historical past. I am aware of the fact that the twentieth-century was not and easy time for China. I think that Westerners, given their own history, often overlook this fact. But if you are aware of the history of China in the twentieth century, it was a challenging and difficult period. I mention this because art is very much a part of history. It is an important part of the culture, and in the struggle to find a new way. Those who were artists had to discover new ways to conduct themselves in order to function as artists. I have a great deal of admiration and respect for Liu Shiming.

CAFA ART INFO: Mr. Liu Shiming created many of his works based on the technique "kneading," while he absorbed and developed this technique from his working experience of artifacts repairing and replicating in the National Museum of China. This traditional Chinese sculptural technique stands in contrast to the emphasis on carving and molding in the Western sculptural tradition. How do you comprehend his classical Chinese technique from your perspective?

Morgan: What I see in Liu Shiming’s work is a very personal, intimate point of view. He is dealing with his family, people and animals that are within his realm, in his village, which is a humbling experience. I think this is the distinguishing characteristic in his work. Honestly, I think his humanity as an artist is very positive in terms of how he brought these subjects to the foreground of our attention.

I am not quite certain as to why so much attention is given to what you call “kneading” in his work. Let me explain how I understand that. While kneading clay is certainly an Asian way of working, particularly in the outlying villages away from urban centers, it is also a technique used by sculptors in the West. But it is used differently. In the West, it is most often found in the preparation stage whereby the artist creates a model, which will later be cast either in bronze or aluminum. But when you are dealing with folk art in the villages of China, the idea of casting in bronze or aluminum is not present because the material is not easily available, certainly not during that time period. The methods are very different in the West from the Chinese point of view. The technique of “kneading” in China is not only the beginning stage, but it is also the finishing stage. This is because the role of Chinese sculptor gives the manipulation of clay an expressive quality. The way the clay is handled by Liu is about discovering this expressive quality in the process of the work. This does not mean that his point of view is Expressionism, which is primarily associated with Western art in the early and middle twentieth century. For Liu, he is more concerned with something very personal and intimate. He is interested that the way the clay is manipulated or kneaded will reveal a distinctly personal feeling. You can do kneading with numerous ways, but I think kneading for Liu Shiming was a method bound directly to the clay. His physical and emotional connection with the materiality of clay was intended to evolve into something significant for him. The works he created are very much about village life and his everyday experiences. I think his work is totally involved with conveying the intimacy of these experiences through sculpture.

CAFA ART INFO: I have talked to an Italian sculptor a few days ago about the use of clay in Liu Shiming’s sculpture. He was also aware of the fact that Liu did not utilize clay in a preparation stage as the Marquette for future work. Instead, those clay or pottery sculptures are the finished-version for Liu Shiming. He did not intend to transform it into another material such as bronze or aluminum.

Morgan: I would say what I saw in the exhibition here was what he wanted his sculpture to be. I think we really have to think in terms of Chinese folk art because that is essentially what he is doing. This idea needs to be respected and understood. There is a message in his work just as there is in any other artist’s work. His art carries a very specific message in relation to village life and to the kind of humble presence indicative of that life. He was really giving us a narrative about living in Chinese villages at the time he worked, but it was also a theme that had continued for centuries in China. I think it was probably more challenging during the 1960s and 70s because of the governmental changes and policies beyond the artist’s control that required him to conform to a certain schedule and way of working.

As you know, in addition to his folk art, Liu was also introduced to socialist realism. I remember in the exhibition there is one of a large work against the wall where we saw a figure tearing down a wall (Cutting Through Mountains to Bring in Water, CN. 劈山引水, 1959). It was a very masculine-looking figure. Then I realized that there were no genitalia on the figure even though he appeared very strong and masculine. Most likely, the figure had to be represented in this way or it would have been difficult to show in a public exhibition.

CAFA ART INFO: Can you share your ideas regarding the influences and significance to the West in terms of holding Liu Shiming’s exhibition in New York and Washington D.C.?

Liu Shiming offers a point of view that at this moment is very important, because his work introduces what has been missing. I think he is a superb artist in that he gives folk-art an important status that brings a way of life into the consciousness of American viewers. His figures reveal the kind of life he was living and expresses it in a highly personal way through the medium of clay.

CAFA ART INFO: Viewing Liu’s work in a contemporary context, do you see there is a kind of “modernity”1 behind Liu’s works?

Morgan: Not really. Liu was not working within a modernist tradition. Even so, he has some feeling for abstract form, which some observers might consider modern. Even so, I do not know how far that can go in terms of influence. Its really more about his work having an affinity with modernity, which is a way of life that falls short of aligning his art with modernism. In either case, I am not sure how important any of this was for Liu. I would rather emphasize what I see as his fundamental role as an artist expressing himself within the context of everyday life through the materials and the methods available to him. Given the period of history in which he lived, the value of this pursuit cannot and should be underestimated. It is a statement on the human condition in China that most Americans simply do not know, and yet, perhaps need to know.

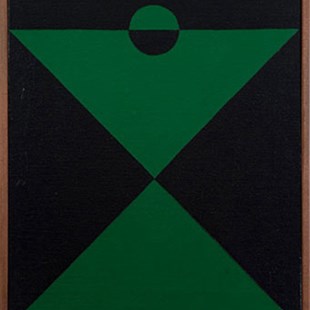

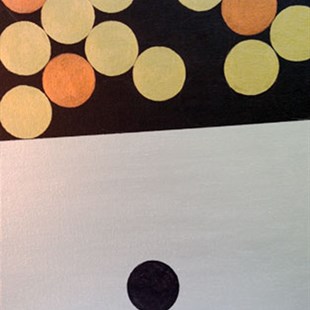

CAFA ART INFO: My last question is about you as an artist. I have viewed some of your early artworks online. You have created a series of abstract paintings and installations. In your personal statement, you mentioned that you are influenced by Tao Te Ching. I wonder what attracted you to explore Chinese philosophy in-depth compared to western philosophy?

Morgan: Yes, I have a copy of the Tao Te Ching right here. I was introduced to it by a friend many years ago. Since then, I have spent many hours reading it over and over. I became interested in the absence of duality. The focus was on the path or the Way. This is the meaning of Tao, and the fact that the Way was not a single Way, but a multiplicity of possible universes that could exist within the Way. It is so different than the kind of ideas taught by Western philosophers from the eighteenth and nineteen centuries. This would include such figures as Kant, Hegel, Kierkegaard and Nietzsche among others. While they are all important to me, the Tao Te Ching gave another point of view very different from theirs. For example, I can read one passage from chapter 48.

I am reading this in the English translation. Even so, I think it offers an important point of view that can help Westerners know and understand themselves better.

“In the pursuit of knowledge, everyday something is added. In the practice of the Tao, everyday something is dropped. Less and less do you need to force things, until finally you arrive at non-action. When nothing is done, nothing is left undone. True mastery can be gained by letting things go their own way. It cannot be gained by interfering.”

This is so beautifully and exquisitely non-Western, but nonetheless an important concept for Western people to understand. Our society must change and become more focused. This is how I have felt for the last forty-five years. This has stayed with me and it still stays with me. I am still reading the Tao Te Ching and still refer to it when I am painting.

CAFA ART INFO: That’s insightful. I think I would read Tao Te Ching again. I read the Chinese version maybe five years ago, but at that time I feel like I did not get a lot from it. And it is interesting to notice when you read the paragraph in English just now, I could not fully connect the corresponding Chinese phrases. I think it has something to do with the cultural differences in translation.

Morgan: Yes there are many translations I have read, and they are not all the same. I picked this one up because I agree with it. When it talks about the master, it talks in a feminism voice, which I think it is interesting. It is very timely for the present.

Translators Notes:

1. Here the interviewer phrased like this as she read the curator’s forward, which stated that artists like Liu Shiming were rooted in the modern transformation of Chinese traditional contexts and local experiences. In the Chinese scholar’s perspective, Liu contributed to the modernization of Chinese sculpture that has taken place in the last one hundred years. At that time, he was a pioneer as he diverged himself from the Western narrative of modernity at the time when most Chinese artists were learning from the West.

After sorting out the interview, the interviewer was questioning the accuracy of using the English term “modernity” in this context to describe a certain period of China or an artist’s avant-garde contribution in China’s 20th century. Also, its associated word “modernism” acts as a significant component in Western art history.

Obviously, Liu’s choice and art provided sculptors in his time with a sort of insight in terms of looking back to Chinese tradition and making traditional culture more “contemporary. ” So when the interviewer says “modernity” here, she is actually trying to explore the insight of Liu’s work from the perspective of the contemporary art world on the development of current and future art.

Section two: Conversation between Professor Robert C. Morgan and Mr. Liu Wei

The second part was a conversation between Professor Morgan and Mr. Liu Wei. They discussed Liu Shiming’s sculpture themes, techniques and his working state as well as relative topics in detail.

Morgan: I think it is important to recognize the historical and cultural time in which Liu worked. This gives some insight into where China was at that moment and where China was attempting to move forward in some way. I dislike putting it that way because it sounds too Western. It is less about moving forward than moving towards some kind of fulfillment. I am wondering how Liu Shiming would see that from his point of view.

Liu Wei: A lot of works you see here in this exhibition actually have been created around the 1950s to 1960s. Actually my father is a man who really enjoys observing people and daily life around him, especially those ordinary people at the bottom of society. He once mentioned that every night before his sleep, those people he met at that day would appear like a film in his mind.

Morgan: Yes this is what I feel. I was talking about how he encapsulates and somehow expresses everyday life in the village. The scenes he represented are very different than, for example, Beijing or even Hanzhou.

Liu Wei: It is interesting to see that things occurred to my father at random. With the time passing by, some things might be gradually obscure in his mind, but what still impressed him after a long period of time should be the key point that indeed touches his spirit. Those memories remaining in his mind can be eventually transformed to the themes of his sculpture.

Morgan: To understand something means that one has something in-depth to express. It is not superficial. I think all Chinese folk art has a considerable depth. An artist like Liu Shiming is really looking at many levels of what is going on around him. Not just one, but a multiplicity of insights and emotions that he is bringing into his consciousness in the process of his work. What I think is important in the “kneading” is that the process of consciousness becomes part of the material. If you can sense that in the material, then it is communicating, not only as art, but communicating the message of how he lives and works.

Liu Wei: In my father’s notebook, he mentioned when he was making sculpture, he would enter a state of “selflessness” or “unconsciousness”. Every time when I saw his working state, he was highly concentrating on his work and nobody can disturb him even himself. I think that one of the reasons that he can enter such a state of concentration would be his practice of Chinese Qigong (CN.气功). He contracted polio when he was a child, which later developed into progressive muscular degeneration. In this case, all his life, he searched for ways to cure himself, including learning Qigong. I think such experience trained his concentration so that he can extremely focus on what he was addicted to.

Morgan: It is interesting to hear about your father’s experience in learning Qigong, the philosophy of energy. There is energy in consciousness. I can sense this in Liu Shiming’s work and wonder as to the source from where it came. I think it is a testament to the fact that you do not need the iPhone to be in touch. You can be in touch through the unconscious. I think in today’s world, and certainly in his, it offers an important point of view.

Liu Wei: He actually entered this state spontaneously. It was a natural process instead of an intentional performance. As he already got the image in his mind, when he began to shape and form his work, it was nothing about any techniques but just a natural and spontaneously process. It is also interesting to notice that all his works were created and finished in his studio. I think he was in need a period of time to digest what he encountered every day.

Morgan: That reminds me of a French artist named Jean-Antoine Watteau. He would go to the countryside and would look at the mountains or trees around him. He would take models and do a few sketches outside, but the painting itself was not done outside but done in his studio. It might be a little more technical than Liu, but there is an important difference between the West and Chinese folk art. I think the way that Liu Shiming releases energy through his work is interesting.

Morgan: There is a formal aspect in the work of Liu Shiming. I think the formality is interesting, but not the point. When I am talking about the formal, I am talking about the form, the volume, the color, and the texture etc. But I think the idea of formalism is too Western to really have any meaning. I think the way that you have described the working process of Liu Shiming is more to the point.

Liu Wei: I think it is related to traditional Chinese culture, the literati culture. From this point of view, the level of artists who merely emphasize form is relatively lower than those who pay attention to the spiritual pursuit.

Morgan: Yes we discussed this at the opening night. We were talking about the differences between the Eastern and the Western points of view. From the early twentieth century, certainly from the position of the Bloomsbury Group in the United Kingdom there was always form and content. You have the material and you express the form. Then there is the content that you trying to express. But from an Eastern point of view, the Chinese add a third element, namely the spirit, which is essential.

If the artist has only form and content, there is a kind of instability, but if you have spirit in relation to form and content, there is no problem with the stability. Rather than two points on the ground, you have three, which makes a tripod. It occurred to me that maybe one of the reasons I gravitated toward Chinese art and culture very early is that I was interested in the stability that is often left out in Western aesthetics. Because the spirit was essential for the literati, going back to the Song Dynasty, the chop was given not for form or content, but for the presence and distillation of the spirit. This begins to appear in the landscapes of the 10th century.

Liu Wei: In Chinese culture, we emphasize to “see a world in a grain of sand”, which means artists would not merely freeze-frame a certain moment as, for example, in a photograph. Instead, they may express the whole process through a small detail. My father worked on art precisely like this. What he would like to deliver is not a still scene but a dynamic developing process. In this case, the scenes he captured are usually with the dynamic and narrative characteristic. Based on this, he wanted to enlighten viewers to consider more questions.

Morgan: In other words, the time is important. The temporary aspect of the form is not just the form in space. Time belongs with space, they are together. Again, this space-time, when brought together, as in astrophysics, there is an absence of duality. It’s a phenomenon that constitutes the universe and all of nature.

Liu Wei: Yes, I totally agree with your point of view. That’s also the point that my father would like to express through his work.

Liu Wei: I learned that you might have some questions regarding my father’s art creation during the Cultural Revolution period?

Morgan: Yes, I brought something. This is a little red book, the first edition that I picked up in Harvard back in the 1966, which was the beginning of the Cultural Revolution. I would share you with a little story. Many years ago, I asked a very important painter about somebody’s essay. I said I do not think he would agree with this point of view. And he said: “You are correct, but the ideas are important.” I think in the West we need to be more educated in terms understanding ideas that we may not totally embrace.. We have to understand ideas from the perspective of history and culture, even if we hold them in question or disagree.

Liu Wei: In my view, I feel like the Culture Revolution was like a big performance art in the world. Lots of people were engaged and Mao was the leading performer. As for Liu Shiming, he actually left CAFA in Beijing as early as 1960. In 1966 when the Cultural Revolution began, he was at Henan as a freshman student removed from any historical activity. He was not involved in these events as he already left the political center at that time.

Morgan: So there were no barriers for him?

Liu Wei: No, I do not think so.

Morgan: But I still think that Chinese folk art, which is how I understand as his major contribution, would be muted more or less. What was his status or experience in that period?

Liu Wei: Actually besides these ordinary people’s figurative sculptures, my father also made a Chairman Mao’s monument for the working-class during that period. Also, he did a sculptural group for the masses in the Zijinshan Park in Henan. Later in Hebei, he was commissioned to work on a large-scale clay replica of Rent Collection Courtyard (CN. 收租院) in 1970. You may realize that my father was always in line with the working-class and mainly created sculptures for the people at that specific period, so he was not involved in any problematic situations.

My father was officially back to Beijing in 1974. At that time, he worked in the National Museum of China for restoring and replicating artifacts. Therefore, in the late period of the Culture Revolution, my father worked in the National Museum of China where he learned about the traditional Chinese sculptural techniques and developed his own sculptural language.

Morgan: I see. That was a good reason to be there. Thank you for taking the time to explain this. I believe your father plays a significant role in Chinese art history.

Interview conducted by Emily Weimeng Zhou

Interviewee: Professor Robert C. Morgan, Mr. Liu Wei

Edited by Professor Robert C. Morgan and Sue/CAFA ART INFO

View of the interview and the exhibition courtesy of the Asian Cultural Center, New York

Portrait of Robert C. Morgan photographed by Sebastian Piras

View of artworks courtesy of interviewees