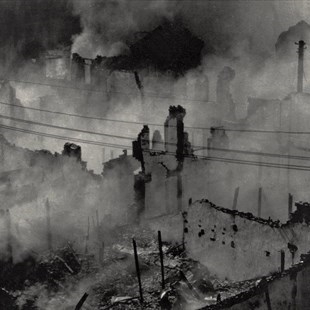

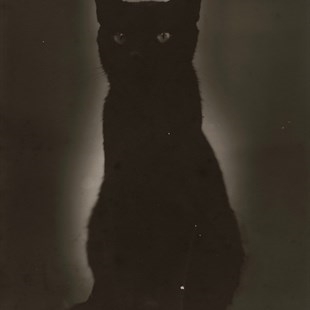

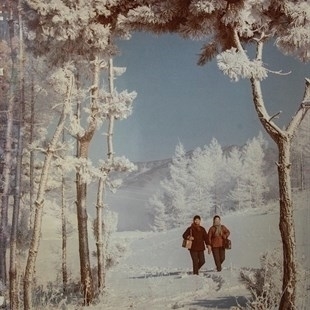

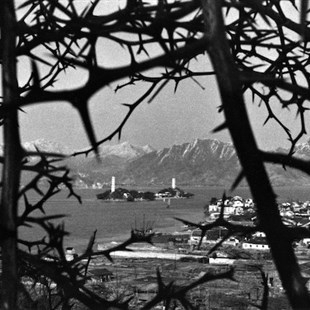

From Aug 20 to Dec 25, 2022, Beijing Inside-Out Art Museum presents its lastest exhibition “Infinite Realism: Humanism in Chinese Photography from 1920s to 1980s”, featuring the evolution of photography as a creative medium in China.

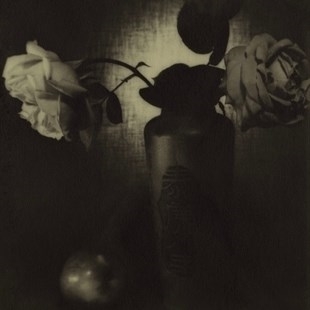

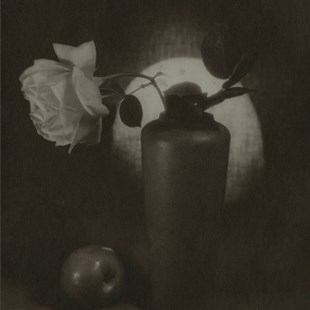

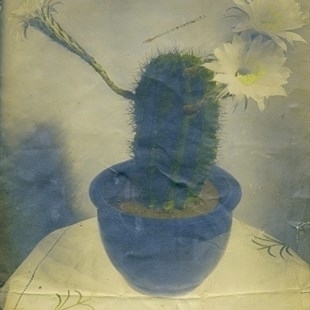

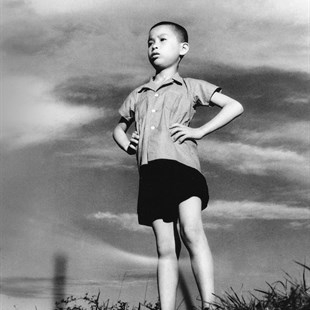

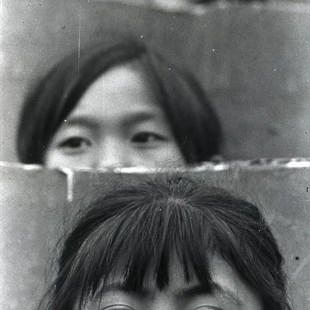

Exhibition View

When photography was introduced to China in the mid-1800s, it was mainly used for visual documentation and as a tool for portrait drawing. It was not until the 1920s that the artists expanded the medium’s capacity. As China faced numerous crises in the early 1900s, the political movement of communism developed. Proletarian revolutionary literature and art caused a rift in the Chinese literary and art circles. Creatives grappled with grounding their work in reality and the experiences of ordinary people. With this renewed interest in reality, photographers recognized the possibilities of the medium and began injecting humanist ideology into their photographs. On the one hand, the first-person camera-eye perspective of a lens can express the subjectivity and thoughts of the artist operating it. On the other hand, photographers can document social reality, recording the turbulence of a political moment. Because the photographic medium interacts directly with reality, photographers are also uniquely positioned to intervene in and alter reality. At the same time, artists explored the artistic, formal qualities of photography separate from political meaning. This interest in “art for art’s sake” rose from the liberal value of individualism was another facet of the humanistic practice of photography.

After World War I, artists in Europe and North America returned to realism to express their state of mind, halting the avant-garde experimentation of the decade prior. In the 1930s, socialist realism was introduced, upheld, and regulated by institutional guarantees and restrictions in socialist countries. Artists and literati in socialist countries and liberal democracies hotly debated the definition of realism. In the process of its policing, realism became ideological, causing many creators to reject the term. Socialist realism was introduced in China in the 1930s as other types of realism were accused of being subjective, and therefore bourgeois. Since then, realism has been a critical concept and method in Chinese literary and artistic practice. After the 1940s, a pragmatic Chinese political environment instrumentalized socialist realism to promote nationalist dogma. A rigid form of socialist realism became dominant, constraining the development of realist methods and theories.

Exhibition View

As socialist realism became chained to ideological principles and a rigid style, artists and literati have challenged these limitations and debated the concept of realism. These debates rose out of creators’ resistance to conforming to the confines of a single ideology. In 1956, Qin Zhaoyang wrote in “Realism - The Broad Road,” “I think the shackles of dogmatism on literature and art are not only in China, but global. It is because this situation is worldwide, that it is perhaps more difficult to overcome.” Because of its close relationship with ideology, it is politically complicated to interrogate how the constraints of realism generated dogmatic, formulaic works of literature and art.

In 1963, the French literary critic Roger Garaudy published the book On Realism Without Borders. In response to the tendency to limit realism to mechanical materialism, class theory, and sociology, Garaudy declared: “A standard of great realism can be drawn from the work of Stendhal and Balzac, Courbet and Repin, Tolstoy and Martin du Gard, Gorky and Mayakovsky. But what do we do if the work of Kafka, Saint-John Perse, or Picasso does not meet these standards? Should they be excluded from realism, from art? Or, on the contrary, should the definition of realism be opened up and expanded, giving realism a new dimension by including these peculiar contemporary works, so that we can integrate all these new contributions with the legacy of the past?” His answer was the latter. The French writer Louis Aragon, who turned to socialist realism in the 1930s, expressed his support for Garaudy in the preface to his book On Realism without Borders: “The fate of realism is not guaranteed once and for all, but rather depends on the valuation of new facts." In contrast to a predefined, dogmatic realism, Aragon defended realism as a philosophy and creative approach that confronts an ever-changing reality. Discarding everything that does not represent a dogmatic sense of “reality” from the category of realism is to castrate it, reducing its generative potential. Rather than limiting realism to realistic forms, realism should be understood through the more inclusive concept of authenticity. We should consider realism from another perspective, as a complete artistic practice. In doing this, we can understand its ability to encompass the full diversity of aesthetic experiences.

Exhibition View

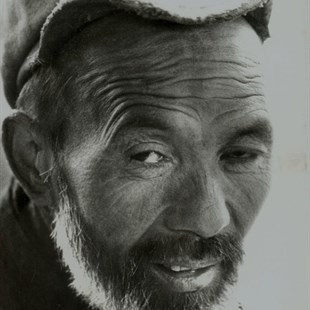

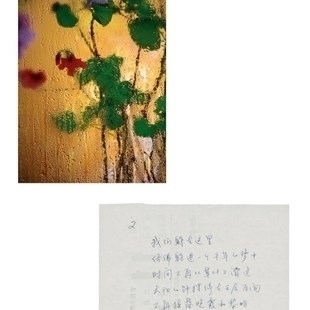

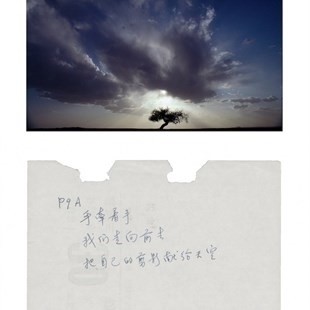

“Infinite Realism: Humanism in Chinese Photography from 1920s to 1980s” showcases the emergence of alternative realist practices in Chinese photography. The works in this exhibition break the formal rule that realism must appear “realistic.” They transcend the modernist dichotomy between art and reality and refute a simple equation between realism and reality. The photographs on view bring humanistic awareness into dialogue with history and reality. The works express photographers’ individual, penetrative gazes on reality, as well as their multi-layered photographic interpretations. The exhibition presents a broad picture of realist practices. In this picture, human beings—as observers, recorders, and photographic subjects—as well as ideological motives and the photographic content, are at the core of consideration and manifestation.

Edited by CAFA ART INFO. Courtesy of Beijing Inside-Out Art Museum

Infinite Realism: Humanism in Chinese Photography from 1920s to 1980s

Infinite Realism: Humanism in Chinese Photography from 1920s to 1980s

Curators: Carol Yinghua Lu, Zhou Dengyan

Exhibition Dates: Aug 20- Dec 25, 2022

Address: Beijing Inside-Out Art Museum

No.50, Xingshikou Road, Haidian District, Beijing