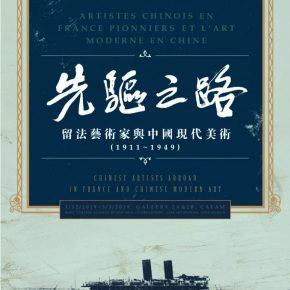

On January 12th, 2019, the exhibition entitled “PIONEERING: Chinese Artists Abroad in France and Chinese Modern Art (1911-1949)” hosted by the Central Academy of Fine Arts (abbr. CAFA) and jointly co-organized by the CAFA Art Museum and Long Museum, was unveiled at the CAFA Art Museum. The exhibition highlights the phenomenon when Chinese artists studied abroad in France in the first half of the 20th century, a generation of art pioneers went to study at École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts de Paris and they systematically studied art disciplines such as oil painting, sculpture, drawing, color and so on. Most of them returned to China after they successfully graduated, and they then brought with them academic art schools in the West such as Classicism, Realism, Modernism and so on back to China. New art forms, languages and concepts brought vitality to the overall developments of Chinese art, and the most important development was that oil painting started to grow in China and it became a style for Chinese artists to recognize and portray the world, which also greatly contributed to the modern transition of Chinese art from traditional expressions.

The artists who studied in France and included in this exhibition, have focused on Western plastic arts with oil paintings as the key. This exhibition takes oil paintings as the mainstay to construct its narrative on “PIONEERING.” The emergence of oil paintings in the Chinese art map did not begin with artists who studied in France. In the 15th century, the Van Eyck brothers, Hubert and Jan perfected the oil painting techniques, and oil paintings were introduced to China with the early missionary activities in the 17th century. Giuseppe Castiglione and other missionary painters were accepted by the Chinese court, thus the concepts and expressions of Western oil paintings also brought some stimulation to Chinese ink paintings which had an independent system, however they always believed that the oil paintings “had no techniques in brushwork, they were meticulous but artificial, so that they were not worthy of literati appreciation.” The core concepts of light and shadow, perspective and structure, etc. that oil paintings followed were not adopted by Chinese painting. Although some painters later mastered a certain degree of realistic skills in Western classical oil paintings, such as the teaching activities of the Tushanwan Painting Gallery and the commercial creation of paintings for export. These early collisions and practices did not succeed in bringing oil paintings into China. It was not until the rise of interest in studying abroad in the early 20th century that this passive absorption state was changed. A group of international students crossed the ocean to study Western art and they returned to China after they graduated, they ran art schools and taught art in China. This was a unique event of Chinese art in the 20th century since oil paintings have also officially been involved in the narratives of Chinese fine arts.

Actually there used to be enthusiasm for studying abroad in Japan before France. Gao Jianfu, Li Shutong, Chen Baoyi, He Xiangning and others entered the Tokyo Fine Arts School to study oil painting, sculpture, graphics, etc., and they exerted a tremendous influence on the developments of Chinese art. Studying in Japan might have the advantage such as similar cultural background, relatively short trips, and cheaper expenses. However, the art of Japan at that time was also established after the return of Japanese artists from France. When the conditions were mature, Chinese art youths still turned their attention to the distant Europe. After all, oil painting is a European tradition, and Europe is the holy place of oil painting. European oil paintings have a long history and a complete system. In addition to the conditions of schools and faculties, Europe also had a systematic museum collection of oil paintings, which perfectly provided opportunities for students to grasp the language changes and conceptual evolution of oil painting art in various periods. It was also worth mentioning that Japan in the early 20th century was the source of the Chinese revolution. Students studying in Japan had more or less revolutionary ideas. By contrast, the artistic motives of students who studied in France seemed to be purer, as they had firm pursuits in art, and they preferred to advocate academic freedom as well as art for art’s sake, so that they could grasp the essence of Western art.

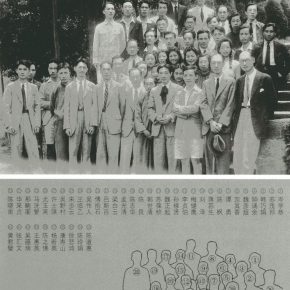

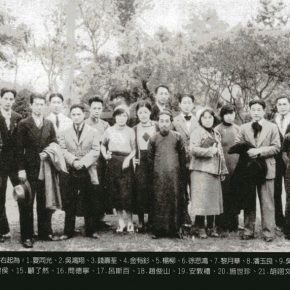

Studying in France, mainly referred to studying at École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts de Paris, which was almost in sync with the Republic of China. Since 1911, when Wu Fading began studying there, a large number of Chinese art students studied there. By 1949, more than 40 Chinese students that had studied in France had become renowned Chinese artists whose practices had profound influences on Chinese fine arts. This is also the framework and structure of the exhibition narrative in “PIONEERING.” From the perspective of global art history, until the end of World War II, Paris had remained to be the center of world art. Artists from all over the world, including China, gathered on the banks of the Seine to form a flexible, open and diverse art network. It was so difficult to classify the creative style by this group of artists and generalize it into a concept. Art historians can only refer to them as the “Paris School” based on their active regions. When we talk about this concept, we often talk about Marc Chagall, Chaïm Soutine, Amedeo Modigliani, etc. Chang Yu and Pan Yuliang from China were also a section of this artistic phenomenon. In the early 20th century, Paris itself was also an art city with many artistic styles and genres. In the usual descriptions of art history, Paris was staged with a series of modernist art schools such as Fauvism, Cubism, Expressionism, Dadaism and so on. But what cannot be ignored is that the classical Realism of the academic school still occupied the official artistic discourse. If not, it would not have promoted the birth of Modernism. Chinese artists studying in France although they differed in their individual aesthetic orientation, they also led to the influences that Chinese students had received from various art schools, so that various styles of oil painting has also occurred and developed in China. This directly resulted in the unique phenomenon of Chinese oil painting. The art revolutions in French oil paintings experienced a linear narrative from classical to modern, while China underwent a jumping “French model” as there was an official taunting of the “Fauvism” voice in France while there was also a “Dispute between Xu Beihong and Xu Zhimo” in China, both being academic discussions.

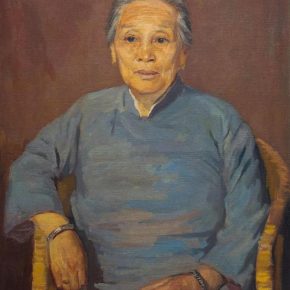

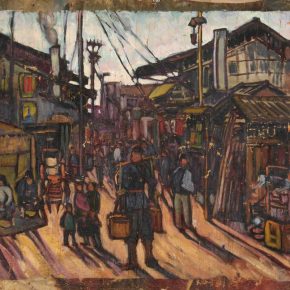

Oil painting was accepted in China not just for those who studied in France. However, it was because of their studies that oil paintings really embarked on a developing path in China, and it happened simultaneously in both Realism and Modernism. Most of the students who went to France to study in the traditional colleges were realistic painters. The exhibition also featured a topic on “QUAND ON BOIT DE L’EAU, ON PENSE A LA SOURCE”, showcasing the latest generation of art masters of the French Classical school such as Jules LENEPVEU, Pascal DAGNAN-BOUVERET, François FLAMENG, Paul Albert BESNARD and so on. Xu Beihong, Li Chaoshi, Yan Wenliang, Lu Sibai, Han Leran, Tang Yihe, Wu Zuoren, Dong Xiwen and many others accepted the traditional French training in realistic techniques. Among them, Xu Beihong had the greatest influence. After he returned to China, he presided over the Art Department of the Central University and served as the President for the Central Academy of Fine Arts. He advocated “Realism” in creation and teaching, formed a basic training system focused on drawings while emphasizing the precision of modeling, pursuing the sense of volume, light, and weight, so that his influences covered the entire Chinese art world until today. Meanwhile, a group of Chinese students were influenced by the modern art trends surging in Paris at that time, such as Lin Fengmian, Pang Xunqin, Fang Junbi, Pan Yuliang, Chang Yu, Wu Dayu, etc. They praised Monet, Cézanne, Matisse, Picasso and other masters while they turned their attention to the art form itself, from the specific external world to the uncertain spiritual world, from loyalty to the natural object to the inner imagination and the inner visual performance. After he returned to China, Lin Fengmian presided over the Hangzhou National College of Art and greatly promoted the developments of Formalism in China.

Academic art is the most brilliant representative of French art. Since the 17th century, France has replaced Italy as the center of world art. After the Great Revolution, France began to modernize its education system. École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts de Paris has replaced the previous art workshops on the stage of art history and promoted the development of many art movements in France. An undeniable fact, is that the French classical academic realism in the early 20th century was in a passive, critical, and fading dusk state. According to the general history of art, the academic art developed by the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century ignored an artist’s individual freedom and creativity, thus they were rigid and conservative, and completely separated from realistic life. It avoided social and cultural thoughts in spiritual connotation, as academic art took edification as the sole purpose which reduced its painterliness and tended to be vulgar. Therefore, while studying the history of art in the early 20th century, compared with the modernist art genres such as Realism and Impressionism, academic art was often regarded as a negative example, a reactionary and bad art, as the background that avant-garde and modern artists bravely rebelled against it. Another undeniable fact is that French classical academic realism has returned to its glory through the dissemination of Chinese students on the soil of art in China. In the 20th century, China was in a revolutionary environment with internal and external troubles, as realistic art conformed to the needs of revolutionary propaganda, thus it was greatly admired. After the founding of the People’s Republic of China, the creation of a favorite art form for the workers, peasants and soldiers became the principle followed by Chinese artists, thus realistic art was strengthened and perfectly combined with the socialist realism brought back by those who “studied abroad in the Soviet Union.” While the classical realism of academic art was doomed in France, the behavior of studying in France had inadvertently extended the glory of this European tradition, and it was actually combined with Chinese culture to produce a different kind of vitality. During the contemporary art movements in the Western world that were against easel paintings, Chinese academic art education has always followed this set of painting traditions. Until today, Western art has a tendency to return to paintings, together with Chinese academic art and contemporary paintings, jointly constituting a map of current globalized paintings.

Text by Zhang Wenzhi, translated and edited by Sue/CAFA ART INFO

Photo by Hu Sichen/CAFA ART INFO