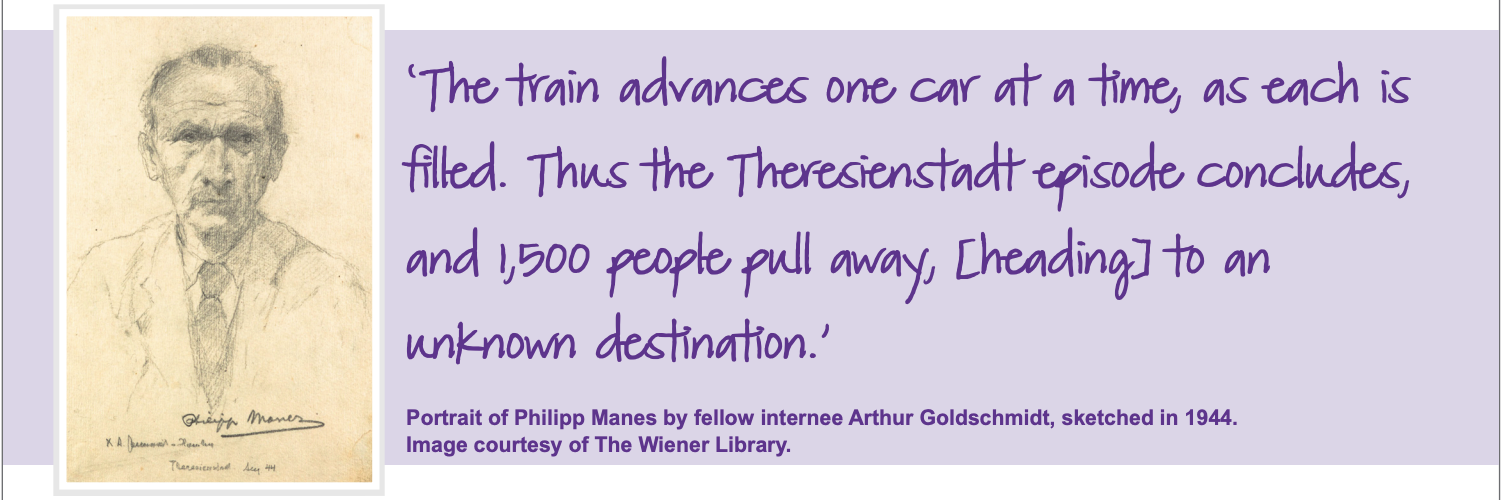

On June 23, 1942, Phillip Manes, a German Jew, embarked on a train heading to the Theresienstadt Ghetto with his wife. “With fearful hearts we sat on the few narrow benches, waiting to see where our exhausted, broken bodies could finally come to rest.” [1] On that day, as always, Phillip Manes recorded this passage in his dairy. In fact, on every day of suffering he would confront the future, such records in the forms of poetry and painting were never cut off.

Different from other concentration camps controlled by the Nazis, although the conditions are equally unbearable, Theresienstadt Ghetto was sometimes used by Nazis as propaganda to convince others, such as the Red Cross, that inmates in their camps were not being mistreated. Therefore, during the inspection period, the authorities tried to maintain the impression of normality for inmates by assigning them work. However, in order to save room for good conditions, a large number of Jews were transferred to other concentration camps that heralded absolute death, such as Auschwitz. The rest of Jews at this seemly benign “transit station,” waited for the next “deportation list” indicating their death.

© The Wiener Library

Theresienstadt Ghetto on postcard, 1909

©Wikiwand

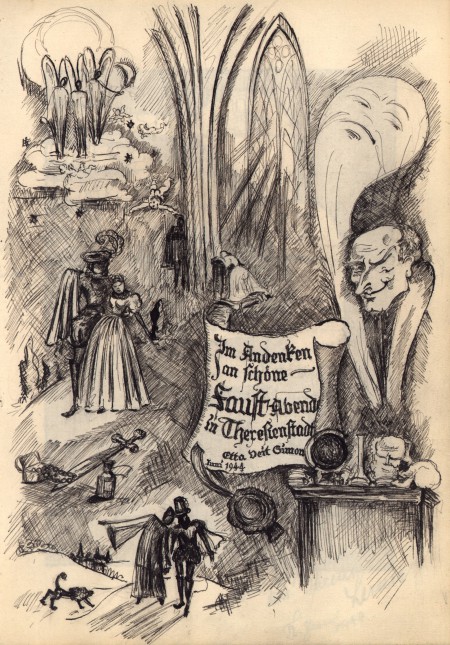

It was under such a “merciful” policy that diverse cultural activities in this “well-built” community were allowed. Phillip Manes began to organize Lecture Series in the ghetto, which later became a regular occurrence for inmates to share their life experiences. In addition, more than 500 cultural events took place, such as lectures, readings, musicals and theatrical performances. The topics of these events varied from religion, history and art, among others. Many professional artists were actively involved, and all inmates voluntarily engaged in organizing and showcasing their passion for these events.

Until 1944, the number of Jews transited from Theresienstadt kept increasing, and Manes’ diary continued to record the spread of panic among inmates. Under such conditions, a series of cultural events had to stop. With the insistence of Manes, the Lecture Series would last until the end of the summer of that year. On October 30, 1944, Manes as well as 2000 Jews were eventually deported to Auschwitz.

Some Artists in Theresienstadt

© The Wiener Library

Nowadays, when people read Manes’ scripts in the Wiener Library, they can hardly imagine what supported him to record life in the form of poetry and painting and organize a number of cultural events in such conditions of suffering. They may also accuse the hypocrisy and cruelty that the Nazis built using the illusion of a beautiful community in Theresienstadt. As the recipients of historical information, it is difficult for us to speculate when confronting the established fate of death, whether the two-year-long cultural events for inmates in Theresienstadt were a temporary release or a catalyst for accelerating fear under the seemly peaceful atmosphere. What we can perceive in Manes’ scripts is his insistence as well as other inmates’ expectations of these events. “I want to continue, to put my whole being into it to the very end and maintain the high quality of the evenings, in spite of the fact that so many participants are missing.” [2]

Drawing by Etta Veit Simon commemorating readings of Goethe's 'Faust' as part of the cultural events in Theresienstadt, 1944

© The Wiener Library

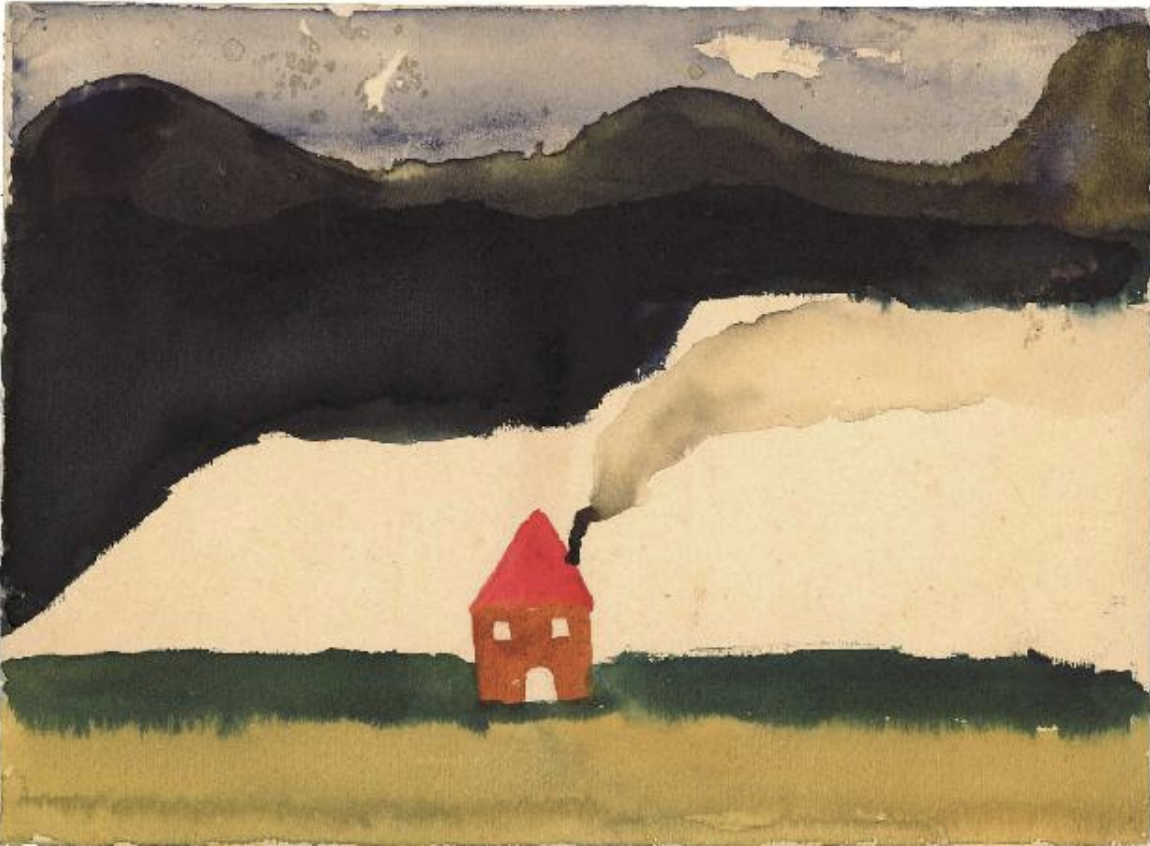

In Theresienstadt, besides the gathering of artists, musicians and scholars, many innocent kids have been forced to come here. “They looked like a group of hungry ghosts, who were taken from the train station to the ‘delousing camp’ in Theresienstadt.” [3] The complexity and strangeness in children’s eyes made adults in the ghetto instinctively begin to consider the kid’s education. “They empower those kids with knowledge, art and conscience to support their soul.” [4] It was in this environment that Hans Krasa created the children opera “Brundibár” and took kids in the ghetto to the stage for a performance. Meanwhile, female artist Friedl Dicker-Brandeis also worked hard to enlighten children’s dim hearts with art. She had been practicing art education throughout her life, thus she managed to care of children’s innocence and offered a pursuit of freedom in Theresienstadt. By doing so, she kept the kids away from darkness and evil, even in such a calamity.

While viewing paintings left by those children now, we can perceive the colors changing from dark to bright and the emotions varying from hopelessness to fearlessness. For people in peace, it is hard for us to say whether art during suffering is cruel or full of passion, but we can expect that some inmates were free, respected and full of hope while they were drawing, singing, and reading.

A child's painting in Theresienstadt Ghetto

Source: Lin Da, As Beautiful as Freedom: Children's Paintings Left in Jewish Concentration Camp, SDX Joint Publishing Company, 2015.

During the Holocaust, whether fortunate or not, the relative mercy policy in Theresienstadt Ghetto enabled the existence of a sort of social atmosphere. Instead of confronting darkness alone, various cultural events provided an opportunity for inmates to exchange and communicate with each other continuously. In this context, artistic activities provided comfort in the darkness and linked up fearful individuals as well as building a temporary social relationship.

In 2005, the haze of the Holocaust had happened half a century previously. Designed by architect Peter Eisenman and engineer Buro Happold, The Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe was officially opened to the public this year. The memorial is located on Cora-Berliner-Straße 1 in Berlin, a city with one of the largest Jewish populations in Europe before the Second World War. Adjacent to the Tiergarten, it is centrally located in Berlin's Friedrichstadt district. During the war, the area acted as the administrative center of Hitler's killing machine. Composed of 2711 rectangular concrete blocks and laid out in a grid formation, the memorial is arranged like a group of tombstones, together with a number of archives related to the Holocaust below the monument.

When the Holocaust monuments were set up all over Europe, Germany chose to build The Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe in its central area and opened it to a worldwide and historical review. This is a nation that is opening up to the world and frankly involved in self- reflection on its dark history. When confronting suffering in the past, people reunite and develop a community, regardless of nationality and national borders, in memory of the dead, while also thinking about topics such as human nature, race and trauma.

The Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, Berlin

Another memorial also represents an unforgettable period of history, namely, the 9/11 Memorial. This monument is located at the World Trade Center site, the former location of the Twin Towers that were destroyed during the September 11 attacks, which killed 2977 people. Architect Michael Arad and landscape architect Peter Walker proposed Reflecting Absence as the design proposal for this project. The large man-made waterfalls merged into the middle of the pool, isolating the noisy city environment. The waterfall symbolizes the lives taken by the attack, the void left behind, and the hollowed-out hearts of the Americans. The names of victims in the blast were engraved on the surrounding walls for relatives to pin their grief on. Technically speaking, the waterfall can also absorb the noise of the city, turning the place to a contemplative sanctuary. The memorial enables a commemorative field in the center of bustling New York City, which connects the history to modern urban life. When the past days is remembered by all of us is integrated into contemporary social life through art, the newly-born society and humanity have to bear the responsibility and reflections from history and continue to move on.

The 9/11 Memorial, New York

Image from Internet

The tragedy and reflection brought about by the disasters allow people to jointly build "monuments" that remembers history. It may be the most intuitive response to the suffering from artistic creation. These "monuments" are not only public sculptures with heavy history and grand narrative, but also represent various emotions shared by human beings – arrogance, scorn, fear, desperation, hope, etc. All these emotions would return to humility and silence for people to reflect on after disasters.

The standing monuments represent periods of suffering made in memorial by history. However, besides engraved history in everyone's heart, what else can people access after disasters through art creation? The exhibition Co/Inspiration in Catastrophes held in MOCA Taipei explored what can people gain through memories of suffering and what role does art creation play in this process. "Co/inspiration in Catastrophes is not to document spectacles with art but to prevent catastrophes from devouring the soul." [5] When confronting disasters, the feedback from art should not be restricted in recording history; instead, artists are required to reflect on the current situation, point out the direction for the future as well as explore the inner power to support the common mind.

View of Co/Inspiration in Catastrophes

Image from MOCA Taipei

What people learned from the Wenchuan Earthquake of 2008 might be the insignificance of people in the face of nature. Artist Ai Weiwei spent four years collecting the collapsed steel pipes from the disaster-stricken schools. He later straightened the distorted pipes and created the installation “Straight.” On the wall behind the installation, the victim’s names were engraved. By doing so, the passing life and the tragedy of the earthquake were calmly recorded in this atmosphere. This piece of work directly confronts the realistic problem when faced with an earthquake, the quality of house construction is far from meeting the standard. Although the collapsed houses were rebuilt after the disaster, the lost lives are untraceable. History will eventually elapse, but what is the heritage of history?

AI WEIWEI, “Straight”, 2008–12

Image from Internet

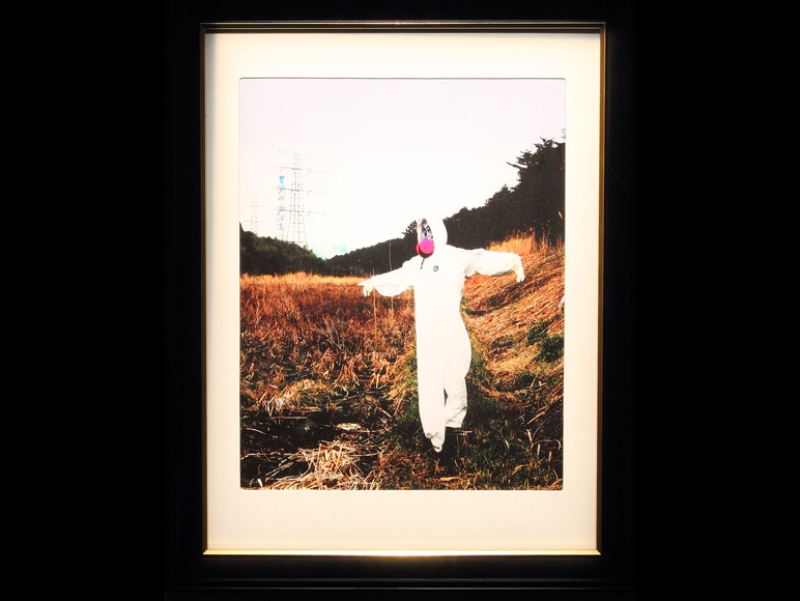

The 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake directly triggered a leak at the Fukushima nuclear power plant, and the whole of Japan was turbulent. Japanese art collective Chim ↑ Pom's response to the earthquake and nuclear power plant leakage is directly reflected in a series of works and artistic activities entitled "REAL TIMES." They entered the area of the Fukushima nuclear power plant in protective clothing to film the silence and tragic scenes like eschatology. They recorded building debris left by the earthquake, deserted farms, and uninhabited streets, etc. A series of multi-media projects finally presented by Chim ↑ Pom, which has aroused widespread social resonance, and also reflected the urgency of post-disaster reconstruction - whether in terms of social infrastructure or public psychology, from the perspective of artistic creation. Over time, the artistic creation that emerges from time to time will gradually be transformed into a form of collective on human memory over time and social progress.

Chim↑Pom

“Red Card”,2011

Courtesy of the artist and MUJIN-TO Production

Chim↑Pom

"REAL TIMES" 2011 Video (11’ 11'')

Chim↑Pom

"Without SAY GOODBYE",2011

Courtesy of the artist and MUJIN-TO Production

People today are familiar with discussing the social attribute of art. When examining and evaluating an artwork, this concept is often included in the conversation. In a stable and peaceful environment, artists create art for their voices of ideal society and institutions in their minds or struggle with the gaps and contradictions between the ideal and reality, or explore the subtle connections and distances between people. When suffering comes to society, artistic creation is expected from another perspective to provide the adhesive for repairing social connections, helping to rebuild group relationships and communities that have been destroyed by disasters.

Each individual acts in a society with different identities, but an inextricable relationship with the whole social group always exists. When society is turbulent due to the coming of a disaster, the outer identities vary from different occupations, backgrounds, and experiences and return to the primary role of being a "person." In this case, the value of common emotional appeal and psychological connection among the social community will be reflected. Artist Sun Zhenhua once mentioned a concept entitled "the arrogation of art" in his article "What is art in the face of disaster? What can artists do in the face of disaster?" It explores the position of art creation in society and before a disaster while emphasizes the artist's dual identity as an ordinary citizen and art creator. If everyone in a particular social group implicitly possesses a collective identity in society, an artist should also attempt to return to the identity of an ordinary person and share the commonality with the whole group in a disaster, rather than make the role of art creation suspend over the social reality.

Currently, the Coronavirus Disease of 2019 is raging, and many artists make their own immediate responses to it. Artist Yang Xinjia discussed the non-functional and “useless” value of art in his recent article “Some Words at the Beginning of Spring.” He holds the view that the function of art at certain time is not reflected in the direct change that art can make; instead, it applies to society to create an energy of positive thinking and reflective methods. [6] Perhaps, art can provide another “documentary” perspective that is different from news and media reports, whilst still affecting people’s memories and emotional connections.

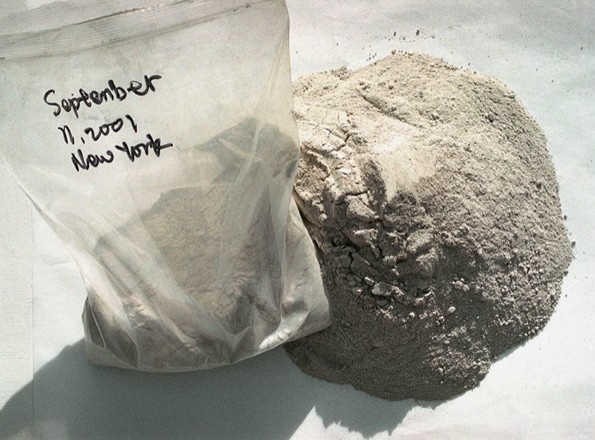

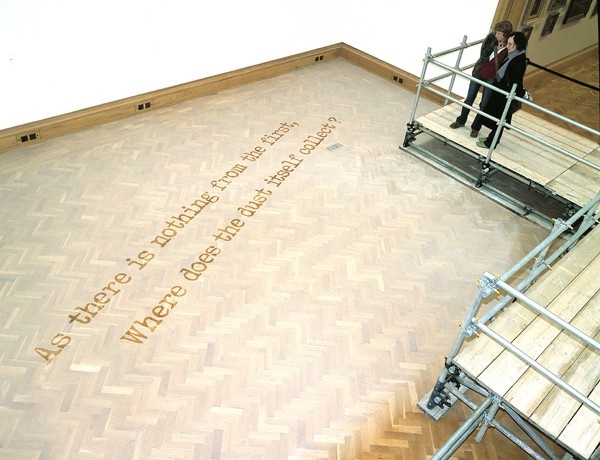

Xu Bing, “Where Does the Dust Itself Collect?”, 2004

Source: http://www.xubing.com/en/work/details/182?type=project#182

The process of human civilization seems always to be accompanied by various suffering. With the development of scientific and technological civilization, people have begun to challenge nature. Consequently, catastrophes have evolved from “natural disasters” to “man-made calamities.” During this process, cultural engraving and artistic creation always emerges from time to time and even realize and raise questions before society’s reflection.

Compared to the shadow of the death from war in the last century, the public that suffer are today facing a spread to a broader corner — the dilemma dominated by grief or the social panic and anxiety caused by a fast-paced urban life. Similarly, with the globalization of all aspects of society, the disaster itself is “globalizing.” Once it breaks out, it is no longer limited to a specific nation but has become a common issue faced by the whole world. In this case, when confronting disasters in the current situation, the challenge for artistic creation is that social relationships focus on far more complex and diverse situations than ever before.

When we retrospect the days of suffering, there is always a reminder that people should be in awe of nature and life. With the gradually globalizing catastrophic situation, art creation should shoulder more social responsibilities instead of being suspended above social reality. In the face of disaster, the response from art should be reflected in the advancement of artistic thought and allow time to precipitate it. It should be something about experience from the history of suffering and affect contemporary society and people.

Perhaps disaster is an unavoidable session of the development of human civilization. Its existence enables human beings to bow their heads and contemplate when they are too ecstatic. It also provides an opportunity for different groups to reunite. And what can art do in suffering? We expect that during this process, art creation always adheres to and links up a gradually expanding social community.

Reference:

[1] Phillip Manes Collection, The Wiener Library London.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Lin Da, As Beautiful as Freedom: Children's Paintings Left in Jewish Concentration Camp, SDX Joint Publishing Company, 2015.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Exhibition text of Co/Inspiration in Catastrophes, MOCA Taipei.

[6] Quoting from the article published on Wechat official account ARTDBL, 2020.

Text by Emily Weimeng Zhou

Edited by Sue