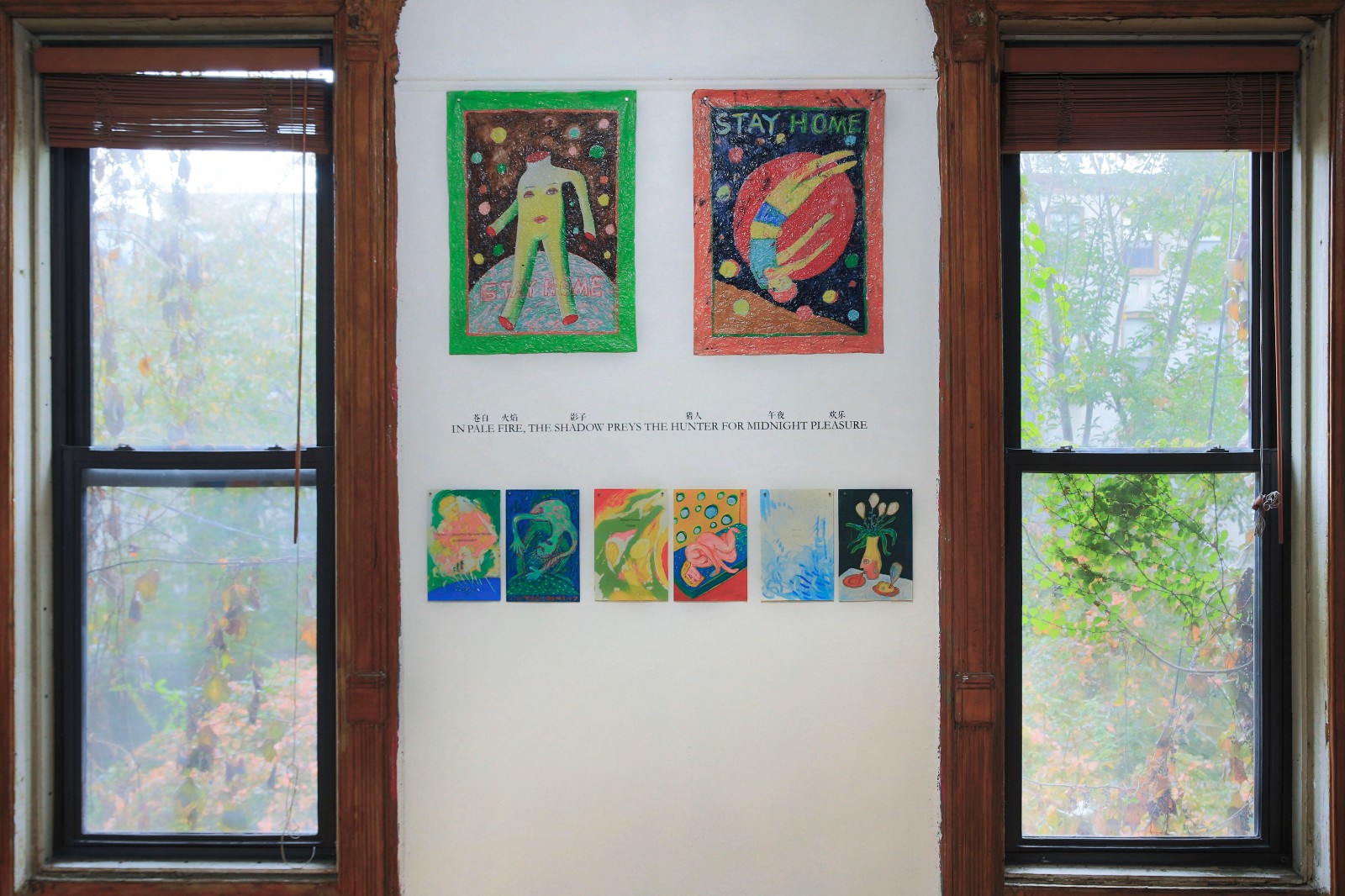

Chen Dongfan: Long Past Dawn, Pirates and Poets Whistle in the Dark installation view, photo by Lynn Hai ©Chen Dongfan, courtesy of Fou Gallery

The pandemic quarantine in 2020 has forced many artists in the United States to stay indoors, and consequently we are witnessing a group of introverted art from this time period. The artist Chen Dongfan just completed two new series, Poster and Story, to respond to his experience during lockdown. The works are featured in the exhibition, titled “Long Past Dawn, Pirates and Poets Whistle in the Dark,” at Fou Gallery. This essay uses Chen’s recent pandemic art as a case study to examine new developments of Chinese contemporary art in the United States. Through analyzing past art criticism on Chen’s works and comparing his recent works with other pandemic arts, this essay argues that the uniqueness of the artist’s sincere expression lies in his pursuit of permanence beyond mundane. While responding humorously to the changing surroundings, the artist returns to the true self. This inward turn during a time of extreme isolation reveals nothing narcissistic, but the artist’s feelings that viewers can sympathize with and a kind of spirit that transcends reality.

Art critics have pointed out that Chinese artists in New York like Chen Dongfan have been pushed to expand from their cultural lineage to respond to local social-political history. Chen Dongfan moved from Hangzhou, China to New York in 2014 and has lived here ever since. In his mural art project, The Song of Dragon and Flowers (2018), the artist engaged with the violent history of Chinatown’s “bloody angle,” and captured the spirit of the street with his artistic interpretation. 1 For Chen’s “Sanctuary” exhibition at the Yeh Art Gallery in 2020, the art critic Wu Peiyue argued that the exhibition broke the boundary of cultural heritages and engaged in a broader social-political discourse. The artist incorporated the multifaceted history of the exhibition venue in his art. The black-and-white mural art “convey[s] a world view through the lens of popular culture rather than offering white elites an updated version of ‘contemporary ink painting’.”2 The issues of migration, culture, and identity are still at the focal point of Chinese contemporary art in the United States. In this relationship of the global and the local, the Chinese cultural elements have opened up and embraced a cosmopolitan imagination. Have the immigrant diasporic communities become an exercise of the global homogenizing or dominating the local?

Under the backdrop of pandemic, artists have been pushed into extreme isolation. The age of globalization suddenly changed into an age of separation. How should we rethink the questions about cultural hybridity and diaspora? When artists in the States are creating art in isolation, Chen’s pursuit of spiritual transcendence beyond mundane became ever more noticeable.

Before delving into the art, it is important to consider the special circumstance of the 2020 pandemic lockdown in New York. Due to the asynchronous outbreak of coronavirus around the world, any discussion about life during the pandemic in New York cannot skip its sudden beginning and dramatic lifestyle changes. In early 2020, before the Chinese New Year, news about the spread of pneumonia in Wuhan broke out. It was hard to imagine that the healthcare crisis that happened on the other side of the earth would soon shut down the largest city in the United States. On March 11th this year, the Oval office delivered a statement about the pandemic and the upcoming European travel ban. 3 A few days later on March 20th, New York closed down non-essential businesses and issued a Stay-At-Home order that lasted till June 2020. 4 With little time to prepare for the beginning of lockdown, Chen and many New York residents lost the support system from their workspace. Indeed, the Stay-At-Home order was not an absolute ban on going out. Activities like going out for a walk or grocery run were still happening sporadically. Yet, Chen lives in the Lower East Side, one of the busiest parts of Manhattan, and his large studio was in Brooklyn. With news reports about the overcrowded and reduced subway service 5, commuting between home and the studio seemed almost impossible.

As a Chinese artist living and working overseas, Chen faced challenges not only from lockdown, but also from the mental stress caused by international politics. Before the coronavirus situation escalated in the United States, the infectious disease in China had already unsettled many Chinese people living abroad. Chinese state-controlled institutes and individuals were all scouring masks around the world for the crisis in China. Trump imposed the China travel ban on Jan. 31st, after which any plans of international collaborations or family and friends’ visits between the US and China seemed impossible. On top of that, the option of returning to China was also almost ruled out. China started a strict control of international arrivals in March, for fear of importing the virus from abroad. Due to the decrease in airline traffic and the increase of panicking people flying back to China, the flight price from the US to China soared to more than a hundred times higher than before. 6 Chinese overseas artists like Chen experienced such a non-physical displacement, where international politics disable their connectivity, if not actual connection, with China and placed them in an isolated mental situation.

When quarantine had just started, people had wobbling expectations for an artist. Although people talked about the difficulties of a new harsh working environment, the stories about great minds keeping their creative work during quarantine in the past went viral. During the Great Plague of London, Isaac Newton was said to have completed a series of works, including the theories of calculus, optics, and gravity at home. Shakespeare was believed to have completed King Lear during the quarantine. Oscar Wilde finished his famous Ballad of Reding Gaol not long after he was released. 7 It seems that extreme situations like quarantine have the potential to advance changes in the creative industry. But we should also be aware that these are the stories of only a small number of people. The pandemic quarantine could be an opportunity to create a bubble for work, but it could also be a bottleneck for creative minds. What new directions have this environmental change brought to Chen Dongfan—whether the direction is a more socially active work highlighting a kind of new awareness, or an inward focus for self-contemplation, or something else—remains the key to understanding the value of Chen’s recent works.

The comparison with other artworks created under a health crisis in the United States shows the uniqueness of Chen’s works. The background of a health crisis behind Chen’s new series and certain themes in these works, like the connection with apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic futurism, reminds us of something we’ve seen in the arts during the 1980s AIDS crisis in the United States. Artists related to the AIDS crisis have similarly brought a surge of emotions of longing and loss. For example, Keith Haring uses apocalyptic images to express his fear and anger in his personal struggle. David Wojnarowicz used post-apocalyptic ruin, the dominant image of New York, to convey a cathartic and often wry and sardonic message. Yet, there’s also a striking difference between now and then. The art of the AIDS crisis feels more politically involved than the kinds of pandemic art we are seeing. In 2020, many artists dealt with the new normalcy by spending more time in nature, observing their personal life, or discussing issues of virtual communication in their new works. For example, the artist Sareh Imani’s video work Center is not a particular point on the earth’s surface documents change and explores the concept of home. Aliza Shvarts’ Hotline, an interactive performance and exhibition, responds to social distancing during pandemic and considers what kind of things we communicate in a mediated distance. Indeed, at this moment, there are also social movements like Black Lives Matter in which the artist community is involved. Yet, in this chaotic year of 2020, health crises and political chaos have created seemingly incessant cacophony in people’s lives. In facing the isolation or even alienation that has come with coronavirus, we need artworks like Chen’s to feel the power from his inner world and use art for connection and empathy. His art shows his concerns for history and civilization beyond reality.

Firstly, in terms of the creation process, Chen chose to turn inward and cultivated a transcendental attitude to life. Isolation has always been an important step for artistic creation, and yet when isolation becomes alienation, ways of art creation have become contained and introverted. Chen used to do a lot of collaborations with other artists, musicians, and writers, and the subjects of his past portrait paintings were often his family and friends. With the quarantine situation, the artist involuntarily had more time than before to be with himself and the internet. His Story series gives viewers a glimpse of his stream of consciousness and a narrative he built using online resources. Surprisingly, the inspiration for his Story series did not start from a line of literary texts, but his random mental strolls, or according to the artist, usually something coming out of nowhere from his brain. Taking Voiceless Secrets as an example, the amusing image of a guy hiding in a fish just passed through his mind. “Isn’t it secretive and amusing?” he thought and then decided to depict this thought on a piece of paper.

Chen Dongfan, Voiceless Secrets, 2020. Oil on paper, 11.3 x 14.9 inches. ©Chen Dongfan, courtesy Fou Gallery.

Quarantine creativity further encouraged Chen to integrate the characteristics of the time in the way he created his works. He endowed his raw thoughts with another layer of meaning by using text from online and a second painting to construct a narrative. When he was unable to access his studio for a few months and it was almost impossible to conduct activities offline, online resources became the most convenient method to absorb new information. After depicting his initial thoughts, the artist combined google translation and keyword searches to find an expression that best describes and complements the original painting. For example, he found the phrase “voiceless secrets” online, which is the title of a poetry anthology that focuses on young people’s struggles. The short title brings to the original painting a sense of mysteriousness and the richness of a literary reference. Ruminating on the meaning of the text and the original painting, he would then proceed to compose the coda—another painting that would ultimately be presented alongside the original one. During this process, the artist experienced a change of role from being an artist, to becoming a viewer looking at the artwork and text from a rather distant position, and ending as a writer wrapping up the work with a coda. Such a process complicated his emotional learning and expression. Although he was alone in isolation, the online information provided him with philosophy references and sometimes shed sideway light on the message he wanted to convey. This mental journey from his consciousness to his selecting of online information reflects the artist’s thinking process.

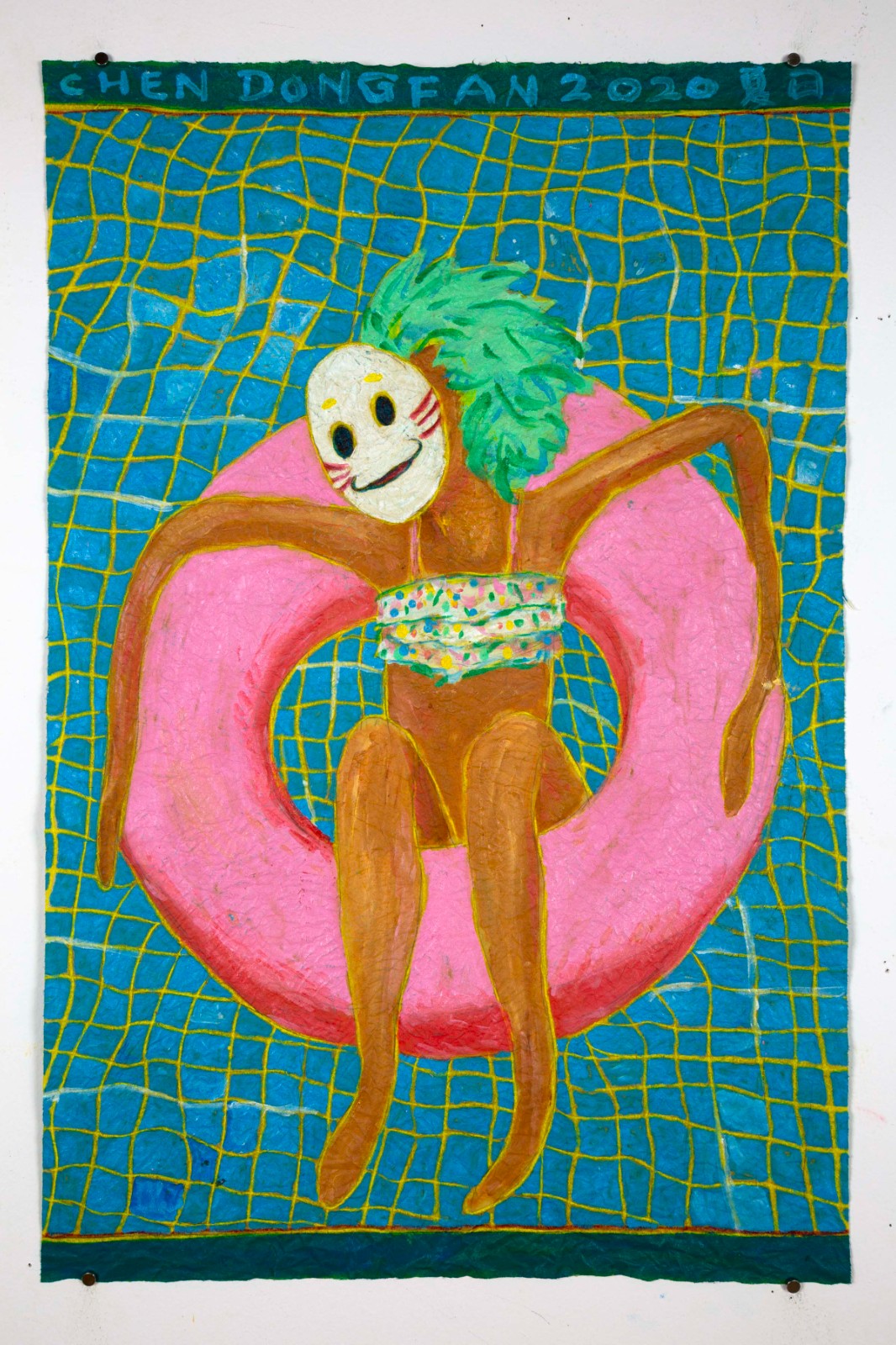

The role of internet in Chen’s art is not about interruption that the artist needs to deal with, but an assistance he employed to look inward. Isn’t this beautiful? That while some of us are still enslaved by social networks, Chen was able to employ online resources to create something truly human? Recently, the Netflix documentary The Social Dilemma has drawn a lot of attention. Some people, for fear of internet companies further manipulating their behaviors, have decided to abandon their social network accounts completely. Some are horrified at the increasingly dominant role social networks play in our lives. Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram became the dominant means for us to communicate with the outside world during the lockdown. When facing the challenge of fast information consumption, Chen was able to intercept the passive process of receiving online information, out of which he was able to create something poetic. Not only was his Story series created with the interplay of internet information, but also some works of the Poster series. For example, the inspiration for the painting Let’s Be Still came from his friend’s Instagram post, a photo of the friend’s daughter floating on their swimming pool at home. Instead of scrolling through innumerable posts like this and forgetting about them, the artist captured his feelings when he first saw the post and created a painting based on it. Both Poster and Story series demonstrate a break from our indulgence in fast information consumption and capture our honest encounter with the internet.

Chen Dongfan, Let's Be Still, 2020. Oil on paper, 27.5 x 18 inches. ©Chen Dongfan, courtesy Fou Gallery.

These two series are Chen’s visual poems. Some may cast doubt on this interpretation by saying that the way his works are displayed in the gallery embodies information overload. The exhibition room at the Fou Gallery contains more than fifty of his recent works. Taking the first step into the gallery, the viewer might be overwhelmed by the amount of information. The Story series contains short literary texts that few visitors would know beforehand. For each group of paintings, the curator wrote an English sentence such as, “Prophets Ask Outsiders To Pick The Void Star On The Whispering Wind” on the wall. In an attempt to make sense of these sentences, viewers are likely to focus too much on the logical connections behind images, instead of indulging in non-linear thinking. In fact, in contrast to the sense of information explosion, Chen’s works do not mean to reinforce fast information consumption. Neither do his artworks call forth linear reasoning to understand. (On this note, the compilation of Chinese phrases printed on the wall, instead of sentences, makes it easy for Chinese-speaking viewers to comprehend the non-linear logic.) One visitor during the exhibition opening commented that his paintings are like haiku, a tight poetic form that contains rich allusion and a clashing of images. Indeed, unlike Twitter messages with a 280-character limit, his paintings are comparable to poems, or to the 6-word novel often attributed – wrongly - to Hemingway (“For sale: baby shoes, never worn”). If we can give each of Chen’s works more time and space for them to tell a story behind, we can easily be charmed by their poetic quality.

Chen’s unique way of creating art and expressing poetry born out of the pandemic quarantine period has fascinated visitors to his show in New York. If we say the Poster series records Chen’s struggle and confusion during quarantine and the Story series uses text to narrate the artist’s self-introspection, why is it important to comprehend something so personal to this artist? His shift away from the social impact of art is not the same as Tracey Emin’s art that uses personal life as art material. His inward turn did not stop at his personal experience, but instead he shifted the focus away from the predicament of time or his personal life, to a quest for universal and philosophical thinking. Chen Dongfan sincerely demonstrates his journey trying to transcend reality, to explore his abstract feelings and imagination that arise in response to their immediate surroundings and a spiritual presence of self in the universe.

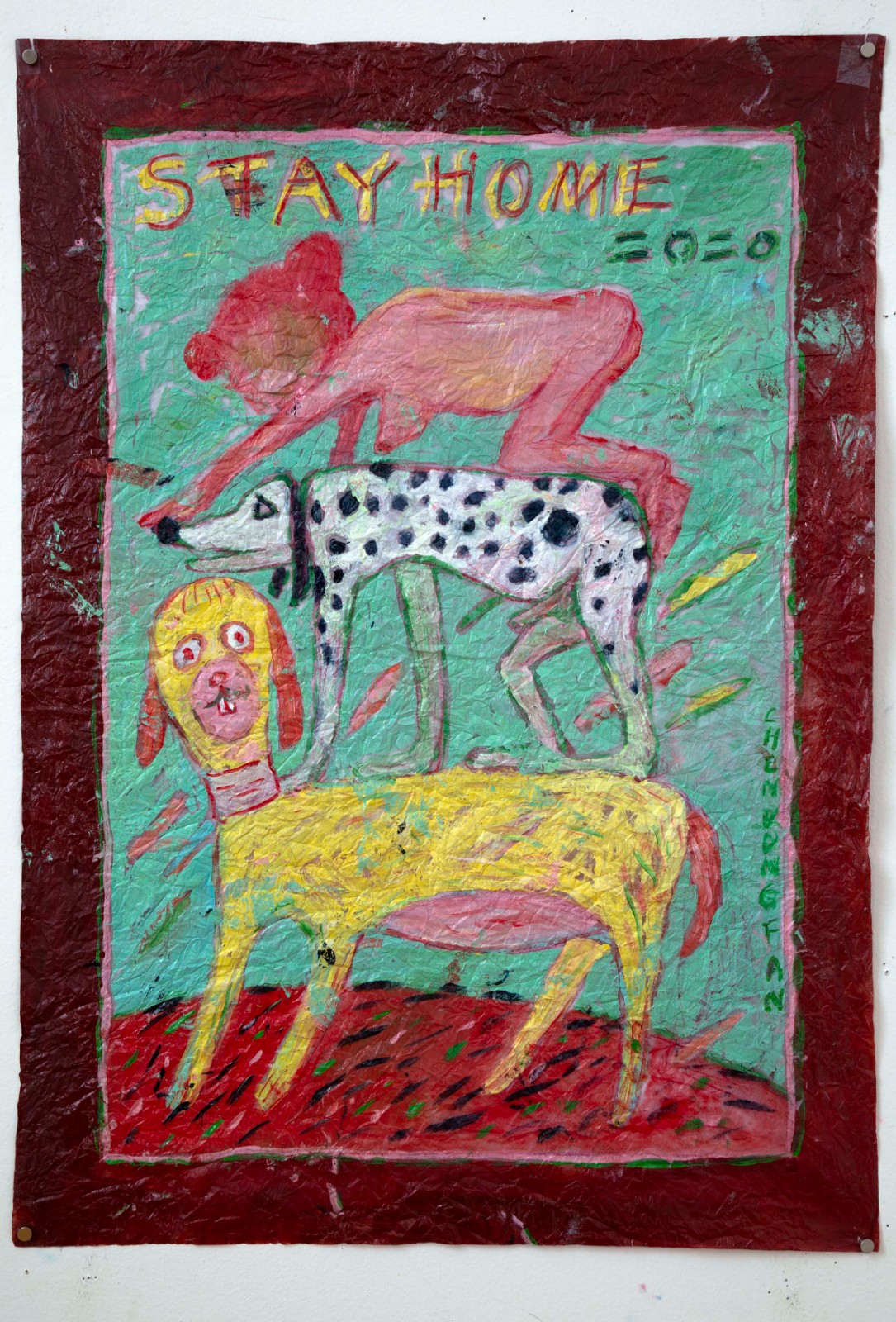

Chen Dongfan, Stay Home 09, 2020. Oil on paper, 27 x 19 inches. ©Chen Dongfan, courtesy Fou Gallery.

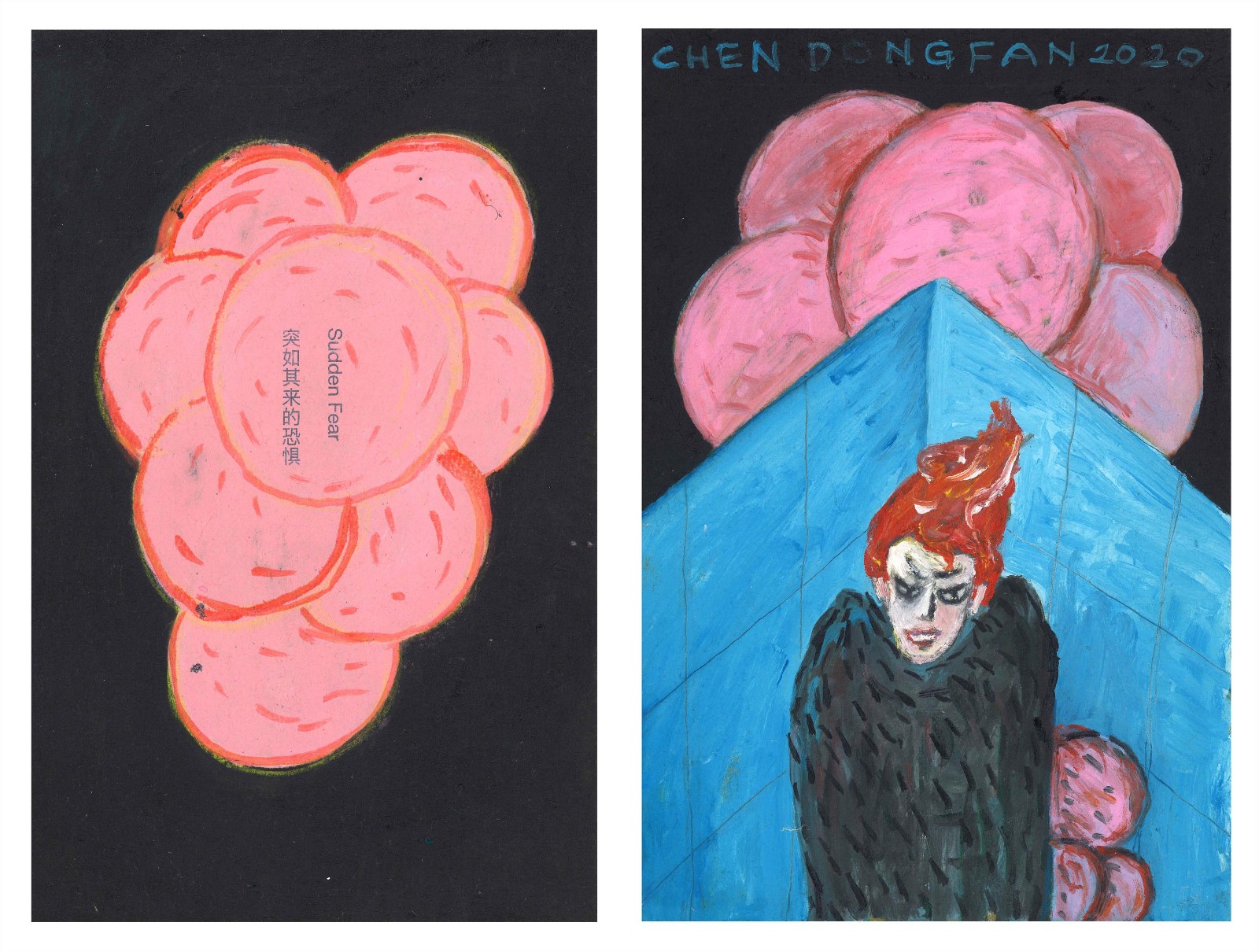

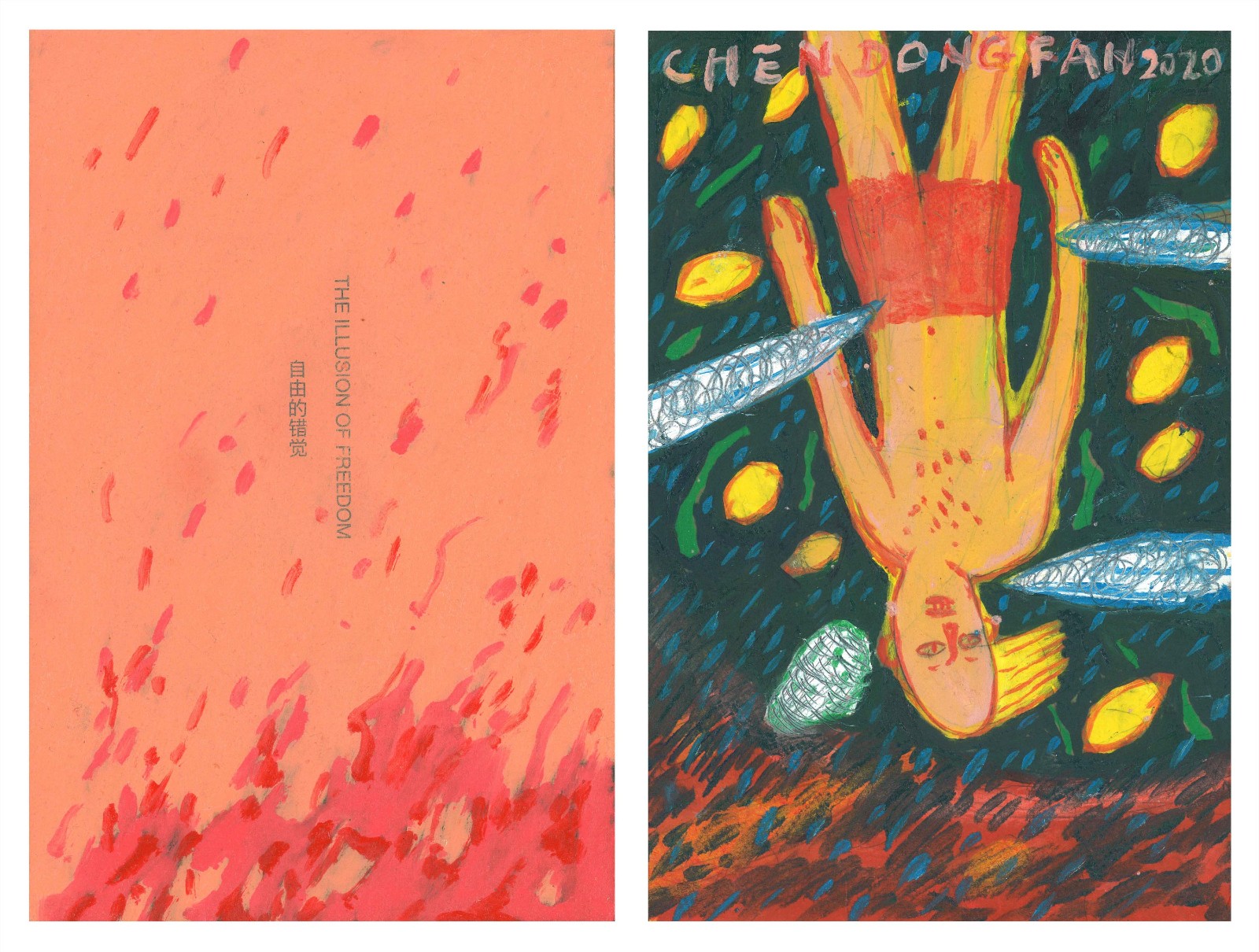

These two series present something so personal and intimate to the artist that a poetic presentation of his thoughts can easily penetrate viewers’ hearts. Although the diversity of imageries in Chen’s recent works made it difficult to summarize what they are about, most of them share a commonality—a personal and fantastical artistic creation. Some of his paintings are based on domestic life during quarantine, but the slight distortion of the real-world or mundane settings allows the artist to make a point. For example, Stay Home 09 was inspired by his wife’s yoga practice, and yet his depiction—the stacking of a woman and two dogs—puts his sense of humor and feelings directly on paper. In a lot of Chen’s works about domestic scenes, we can find this style of magic realism, an inclusion of magical elements in the realistic view. Some other paintings in these two series demonstrate the artist’s fantasy that can hardly be said to have a real-world setting and yet this type of imagination serves as an outlet for the artist to escape and liberate himself. Chen pointed out that when painting The Illusion of Freedom, Sudden Fear, and The Disappearing City, his heart was full of anger and confusion about the quarantine life. For instance, The Illusion of Freedom depicts a man hanging upside-down, with blades protruding out from both sides. The dark green background and the red flames in the bottom seem to indicate the location as hell. Maybe it was intense wrath and disappointment with reality that forced the artist to escape from it and start imagining apocalyptic moments or post-apocalyptic ruins. On the other hand, in paintings like On the Whispering Wind, which depicts a melting green figure floating in the background of dots, viewers can feel strongly a sense of calm and peace. In this painting, the artist seems to place himself as a part of nature rather than an individual. The boundary between the self and the world is blurred. Without a distinction between the constrained and constraints, one can achieve a sense of freedom for oneself. Behind all of the above-mentioned fantasies are the artist’s abstract feelings beyond the observed reality. This kind of transcendence allows an unhindered expression of Chen’s feelings of longing and loss.

Chen Dongfan, The Illusion of Freedom, 2020. Oil on paper, 11.3 x 14.9 inches. ©Chen Dongfan, courtesy Fou Gallery.

Rather than articulating grandiosity of myths, Chen’s art resembles more philosophical comics. For the Story series, the artist’s choice of unrealistic and fantastical elements in his art might quickly lead us to conclude that his unbridled imagination has created contemporary myths. However, both the use of non-mythological elements and the sense of intimacy in his recent works convinced me the Story series cannot possibly be about contemporary myth-making or reinterpreting myths in the contemporary society. The curator Lynn Hai associated Chen’s art with contemporary myth-making, as she believed the artist “discovers their [myths’] new meanings in contemporary life in response to current events and topical opinions.”8 Nevertheless, in the recent two series, the artist mostly used non-mythological elements, like people or subjects from his life, other artist’s works, or his apocalyptic speculative imagination. Some might argue that the definition of “contemporary myth” has extended far beyond stories about supernatural beings in ancient times to some unverifiable descriptions of natural or social phenomenon for the sake of emotional expressions. This fluid understanding of contemporary myth may appear apt for these works. Nonetheless, associating them with myths assumes a sense of grandiosity and transmissibility that are in contrast with the sincere and modest nature of Chen’s works. Just like Chen’s earlier exhibition in Beijing, The Forgotten Letters 2020, the Story series is personal on so many levels. The artworks in The Forgotten Letters 2020 visualize the artist’s emotions during quarantine in a letter format, while the Story series weaved together the artist’s thoughts based on images that popped up in his flow of consciousness. Instead of using strategies to actively put forward an image for social awareness, Chen’s recent artworks channels his unadorned feelings and rumination over problems in real life.

This essay uses Chen Dongfan’s recent series as an example, but the same kind of spiritual pursuit sans self can also be seen in a number of Chinese artists’ pandemic artworks. In the US, away from rapid changes this year, the artist Guo Shulin practiced meditation in life and in art. She completed her 5-6 pm series when living on a sailboat. In Shanghai, a group of artists, including Jia Hui, Wang Yuyu, Yan Bingqian, and Yang Yijia, have also recently carried out a project to record the suspended and chaotic time during coronavirus pandemic. The project named Light Never Brightens Up the Outside (《灯从不照亮窗外》) took place in a deserted office space in the suburb of Shanghai suburb. All kinds of bizarre objects were placed in the space, including some kind of green liquid that filled up the balcony, the fish maw that was hung on the lamp, and two toilets facing each other. On the wall, artists hand-wrote some lines of Gaston Bachelard’s poems.9 Unplanned, Chen Dongfan in New York, Guo Shulin by a seaside in the US, and a group of artists in Shanghai, all returned to introspection and spirituality and created speculative poems in memory of our time.

The United States is still in the middle of a pandemic. Many other pandemic arts are being created now, but Chinese artists like Chen Dongfan catch the viewer’s gaze with his humorous and poetic response to the changing world and his pursuit of a transcendental spirit. Art as a medium carries the artist’s complex feelings reacting to the changing world and his calm observation of his inner self. In the painting Rise from the Ashes, on a ragged paper, an angel with injured wings stands with his back towards us. He leans towards the upper right corner as if he is preparing to take off. The title Rise from the Ashes and the scarlet red floor where the angel emerges out from seems to imply that the angel is a phoenix in nirvana. Chen started this painting when he was finally able to return to his studio. The artist’s recovery from quarantine, the relief in the return to his studio support system, and a sense of hope can all be seen in this work. The presentation of his emotions is so sincere and full that we can relive that moment of his life. The power of this type of art is subtle and long-lasting—before leaving the gallery, I overheard someone talking, “Maybe I can create something if quarantine starts again.”

Living in this particular moment made it hard for us to see how precisely the pandemic has changed us. Maybe in a hundred years, we can easily generalize what kind of change or bottleneck we are experiencing right now. As of now, in a careful examination, we might be able to see paradoxes inherent to Chinese contemporary art. While Chen’s artistic style went against the stereotypes of Chinese art, his art retains a delicate touch of Chinese-ness in the pursuit of spiritual permanence. While his pandemic arts turn inward, they are not a work written to himself, but a visual poem to the world. While his arts portray simple scenes from daily life, they reveal a concern that is universal and transcendental.

1. Remy Tumin, “He’s Painting the Streets Red. And Yellow. And Blue.” New York Times, accessed on Nov.24th, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/27/nyregion/doyers-street-chinatown-mural-chen-dongfan.html.

2. Wu Peiyue, “Chen Dongfan: Sanctuary,” Journal of Curatorial Studies, 9(1): Venice Biennale.

3.“Remarks by President Trump in Address to the Nation,” accessed on Nov.4th 2020, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/remarks-president-trump-address-nation/.

4.“The ‘New York State on Pause’ Executive Order,” accessed on Nov. 24th 2020, https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/2020-03-20-Notice-New-York-on-Pause-Order.pdf.

5. Samantha Putterman, “Photo shows a crowded New York City subway train during stay-at-home order,” accessed on Nov. 4th 2020, https://www.politifact.com/factchecks/2020/apr/07/viral-image/image-overcrowded-nyc-subway-car-real.

6. James Asquinth, “Flight Prices To China Soar By 150% As Travel Restrictions Increase,” accessed on Nov. 4th 2020, https://www.forbes.com/sites/jamesasquith/2020/03/27/flight-prices-to-china-soar-by-150-as-travel-restrictions-increase/#1767537424e0.

7.“Virtual Creativity,” accessed on Nov. 4th 2020, https://chemistry.harvard.edu/news/virtual-creativity.

8. Hai Liang, “Chen Dongfan: The Omniprescence of Myth,” ArtPulse Issue No. 34.

9. Qiao Feifan, “NOV+| 从城市边缘到zoom会议室,年轻一代的艺术机制实验,” TANC艺术新闻中文版, Nov + Shanghai Art Season 上海艺术季特别策划.

About the author

Sharon Xiaorong Liu is a New York-based writer with an interest in contemporary arts and culture. She graduated with a master's degree from Yale East Asian Studies program in 2020, and obtained her bachelor's degree in Art History and Math from Wellesley College in 2017.