Xi Chuan: Hi, everyone! I’m Xi Chuan. I’m a poet, but I often call myself an artistic poet, because I want to be artistic. I’m very glad to be here to share with you my views on art and literature.

My topic today is “The Scope of Artists’ Manoeuvring”, there are two kinds of artists in my view: one is creative artists, who constantly explore and make pioneering contributions to the art community; while the other group consists of artisan artists, who perform well in the jobs in hand, and do better than their predecessors. I call the latter group artisan artists, they are not my focus today. Instead, I’d like to talk about creative artists.

When it comes to creative artists, we have to talk about the “talent of artists”. Most artists are talented, especially the younger ones, and many artists feel they themselves are talented. What is talent, I don’t know. It’s too hard to define. It may be inherent. By reading someone’s book, not necessarily a literary work, we can judge the author—personally, by reading a historical work, I can tell whether the historian is talented. For artists, the importance of talent cannot be overemphasized.

So what is talent? The talent that I’m going to talk about is not about doing a good job that is in hand, which is also a kind of talent. This is what artisan artists do. There’s another kind of artists. You can feel that their talent is overflowing—that is, they have so much talent that they can “waste” it. If someone does not have sufficient talent to waste, they aren’t talented enough; but if they do have, we can be sure that they’re very talented people.

The word “waste” refers to my topic today “The Scope of Artists’ Manoeuvring”. I’d like to elaborate on it from two aspects. From what I’m going to talk about, my friends, you may know that the word “waste” is connotative, and realize the meaning of the word.

Just now I said that I’d discuss the scope of artists’ manoeuvring from two aspects. Before I start the first aspect, I’ll read you a poem. This is an ancient poem. I won’t tell you who wrote it. It was written in the Song Dynasty, named A Weaving Woman’s Resentment. I won’t read the complete poem. It’s about a weaving woman who works hard, weaves a piece of silk that she feels very satisfied with, and then she presents it to the feudal official. But the official stamps a large word on it—this doesn’t appear in the poem, but was known by those who study the literature of the Song Dynasty—that is, the official, who thinks that the silk is of poor quality, stamps a big word on it: “unacceptable”, which means unqualified. This creates a difficulty, because she had spent so much time on this which was in vain. It’ll completely upset the life of the weaver or her family, and their life will become tough. As the poem goes, “My hands have become tired on the loom. My feet on the pedals are full of calluses. I kept weaving for three days, only to cut when the silk was long enough.” She’s been weaving for three days to get a piece of silk. Then, “While weaving I was afraid that when the wind came; when cutting, I used the scissors carefully. Everyone commends the woven silk. I myself think it’s tightly woven and exquisite.” So you see, she thinks her silk is good and is satisfied. “Yesterday morning I took it to the warehouse.” She takes it to the official warehouse. The official checks the silk and becomes angry. But she doesn’t know why. “He stamped a big word on the silk.” It’s the word I said just now. “The ink smudged the silk. Her parents, who took it back and threw down in the house, looked at each other without a word, but just with a rain of tears.” They can’t do anything but take the silk back and cry for it. That’s all about the poem.

Wen Tong, "Painting of Ink Bamboo"

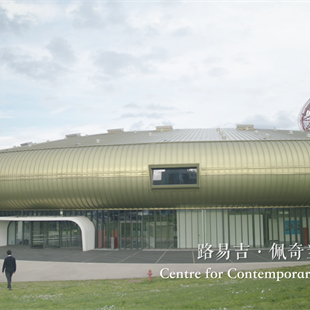

This poem reminds us of the ancient Chinese literati, who wrote about the sufferings of peasants. Such poems are called “pitying-peasants poetry”. But the poem I just read isn’t a poem of this kind. It’s a poem about how hard the life of ordinary people was. The author is Wen Tong, a great painter in the Northern Song Dynasty. Once we talk about Wen, we immediately think of his bamboo painting. This is his painting. Wen Tong is a cousin of Su Dongpo, that is, Su Shi. Generally speaking, in the history of Chinese art, when we read about Wen, we’ll also read something about Su and his opinions, such as, “with painting in poetry, poetry in painting”. This originated from him.

We mention Su when we talk about Wen, and it seems that Wen is affiliated to Su. In fact, Wen was 18 years older than Su, and became a Jinshi, an advanced scholar, eight years earlier than him. it is hard for us to imagine when we see the paintings of Wen. We can be sure that he’s definitely a literatus, but it’s difficult for us to imagine that he wrote such poems as A Weaving Woman’s Resentment, because this has nothing to do with the bamboos he painted. A question will arise: do we understand Wen Tong? I’ve read you the poem. Is the painter of bamboos the author of the poem? Obviously, they’re the same person.

How deep-thinking are the ancient Chinese artists? Do we actually understand the great artists in ancient China? In what way do we understand them? If you know only one side of them, dare you claim that you understand them completely? A lot of questions will arise.

We may even wonder whether we really understand the history of art, because what we read in the history of art is its image and artistic achievements. Then what constitutes the artistic achievements, and how profound are they? Maybe in our minds, if we have all-dimensional understanding of the artists, we’ll have doubts. We won’t be so confident about our previous impression of an artist.

Wen Tong is not an isolated case. Ni Zan, another famous artist in the history of Chinese art, is also a case in point. Many people know Ni’s paintings, whose composition is basically the same. He uses a short-term perspective, a long-term perspective and draws several trees. Most of us have the same understanding of Ni’s composition. I’ve seen and been very impressed by many of his paintings in a museum in Shanghai. In his painting Six Junzi, there’s a piece of land in the front with six pine trees on it, a remote mountain behind, and water in between. This is his basic composition. We think that Ni has a very remote and lofty painting style. To describe his handwriting in inscribing poems in paintings, we even use the word “Qīng清”, meaning very remote, graceful and lofty. This is the way we describe him.

Qingbi Pavilion Collection

Next, I’ll read you one of his poems. Anyway, when I read Ni’s poem myself, I find it shocking and eye-opening. This poem is included in Ni’s collection of works, namely Qingbi Pavilion Collection. If you’re interested and read it, I believe you’ll be surprised. Ni Zan, as a poet, is different from a painter. Ni liked Du Fu who he often mentioned. Of course, he also liked Li Bai and Du Mu. But it’s amazing that he wrote about Yue Fei in his poems, such as To the Tomb of General Yue Fei.

A painter, who was so remote and lofty, unexpectedly admired Yue Fei. People can hardly imagine that. The poem I’ll read is a Song of Chu poem written by Ni Zan, who could actually write the Songs of Chu. The style is different from that of the poems written on his own paintings.

The poem I’ll read is Welcome and See off Immortals at Zhongjingwang Temple. I won’t read the whole poem. Listen and guess whether it was written by Ni Zan. “The immortals leave on the dragon-horse’s car and take the wind away. The wind blows the flags. I’m still melancholy in the wind. The immortals won’t stay long. Their gestures are so graceful. They can travel around the world in a short time. In the morning, they start on clouds in the west mountains, while in the afternoon, they arrive in Lu State in the east.” Hearing this, we immediately think of Qu Yuan, who wrote, “To the northern bank descends the lady Goddess; Somber and wistful the expression in her eyes. Sighing softly the autumn breeze; Leaves fall on the ripples of Dongting Lake. Amidst the white sedge, I anxiously keep watch for my love who will come when the sun sets. Why are the birds flocking in the reeds? Why the nets hanging in the trees? Angelicas by the Yuan and orchids by the Li. I long for my love but dare not speak my thoughts. My heart is trembling as I gaze afar. Over the waters which are flowing fast. Why are the deer browning in the courtyard?” This is part of his poem named The Lady of the Xiang.

I read you Ni’s poems in the style of Songs of Chu, and you’ll find that he was a master of the genre. Once you realize this, once again you’ll be shocked by such an artist, who painted such a remote and lofty painting, and who could actually write Songs of Chu. He could experience the world through Chu culture and Qu Yuan.

In the works I’ve read about art history, no one has mentioned the relationship between Ni Zan and Qu Yuan in the Warring States Period. No one has mentioned this, but now we have revealed this secret. We have to ask ourselves the question: how profound can an artist be?

There’s another point. You have to think twice about what art historians have given us that seems to be the answer. For example, I know that James Cahill, a great art historian in the United States, thought that Chinese ancient paintings never depicted death or wars, which hasn’t been depicted in paintings in the Song Dynasty before the literati painting, neither. However, it was doubtful in the Qing Dynasty. Because there were painters from the West in the royal court, who could depict the martial arts of Emperor Qianlong. But before that, our painters didn’t draw these things. James Cahill said that there was something that ancient Chinese paintings didn’t depict. No painters painted them.

But the poems I just read will obviously remind us that ancient Chinese artists, actually all artists, weren’t satisfied to be just artists. They were different from us today, who may think of ourselves as just a painter, a sculptor or a designer. The ancient Chinese artists were actually much more profound than they showed us.

It makes us reflect on James Cahill’s statement, where he didn’t mention their writing. When we reflect on this, we’ll find that something the painters didn’t paint was written in their poems. They wrote it down. That is to say, for the ancient Chinese painters, they existed in many ways. But for contemporary art history, we record just one side of them. We write it down as the history of art.

There were many other ancient Chinese painters who were also poets. Above are just two examples. For the writing of our literary history or our art history, we just extract a certain side of an artist or a poet.

Pablo Picasso

Salvador Dali

I think of another famous example—Wang Wei, who featured prominently in China’s literature history. But he was also a great painter. This is true both at home and abroad. Many great foreign artists may have some other sides that we pay little attention to. In two days, there will be a large exhibition, Picasso’s exhibition, held in Beijing. Picasso is also a poet. Do you know that Dali is a great painter and he is also a poet? In the Western tradition, there are also cases that an artist crosses the border—just as I’ve mentioned, the talent of an artist overflows, and you feel that he/she is “wasting”. He/She shows his/her talent in more than one aspect, scintillating in many ways.

Let’s move on to the Renaissance, the European Renaissance. You’ll find an important artist in the Renaissance, who is also a poet. It’s Michelangelo. Many people know Michelangelo’s art and sculptures, while I don’t know if you know that he’s also a poet. He thought he could communicate with Dante through spirit. Dante, who Engels called the last poet in the Middle Ages or the first poet of the Renaissance, wrote Divine Comedy. I believe that only professional readers can read it, while amateur ones will definitely leave it untouched. Dante’s Divine Comedy is a long verse, including chapters of Inferno, Purgatory, and Paradise. Michelangelo was the reader of Divine Comedy. I remember I’ve read two poems of Michelangelo, the first of which is related to Dante’s Divine Comedy.

In fact, we’ve got Michelangelo’s poetry collection translated in China, but we didn’t pay much attention to it Michelangelo wrote in his poem, “He comes from heaven, with ordinary eyes see the existing hell and the hell that will not last, and then returns to God’s side in heaven, showing us his great glorious talent. The bright star reveals the light in the dark crimes that have fallen on earth, but the earth is also my lair. For him, the bad land of mankind is not a prize. God, you created him, only you can reward him.” Only God can reward Dante. “I want to make it clear: Dante’s works never delight those who aren’t grateful or civilized. They only ruin justice and hate. However, I wish I could be him!” That is to say, Michelangelo wished to be Dante. “With cold stares and abandonment he was born; he suffered from such a fate—if this is the case, I won’t hesitate to give up everything precious.” This is what Michelangelo wrote about Dante. Let’s think about Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling in the Vatican, whose spirit is completely in harmony with the that of Dante. In his paintings and sculptures, we can feel that Michelangelo is really not one of us, because he has a great soul directly connected to Dante’s.

Only such a person can be called “a Renaissance figure”. We in China often discuss whether China should carry out our version of the Renaissance. This has already become a topic worthy of discussion. And some people are anxious about this—why can’t the Renaissance take place in China? But once we read Michelangelo’s poems and associate them with his visual art works, we’ll know that the Renaissance figure can’t be passed on. You can’t call yourself a Renaissance figure with only a little knowledge. Behind the state of mind and the creation are so profound and deep spiritual resources, which, from their art works and literary works, we can realize. Art itself which is constantly developing and changing. You can say that Michelangelo’s works are classical art, and contemporary art is different. Contemporary art may not include Dante, but whose spiritual strength actually determines how much you can achieve in contemporary art.

Leonardo da Vinci

Among Michelangelo’s contemporaries, the one I admire most is Da Vinci. I know that many people admire Van Gogh, but I admire Da Vinci, not only because of his famous Mona Lisa. Da Vinci is completely a Renaissance figure.

I’ve read his biography, which for the most part discusses Da Vinci as a scientist. In that book, Da Vinci is a great scientist, but he has no idea about mathematics. It’s impossible for a scientist to know nothing about mathematics. But Da Vinci makes up for his shortcomings in mathematics with paintings. He draws a lot of notes. Besides painting the mechanical sketches, he has also done a lot of research. These are Da Vinci’s notes on anatomy, completely from the perspective of a scientist.

I once heard an anecdote about Da Vinci. During his time, there was the punishment go hanging. The Italian people also went to see the hanging. Once the person was hanged, the audience would react. But it was recorded that Da Vinci, who was quite calm on this occasion, was observing the facial expression of the dying person, and his look at that time, wasn’t human, hard to describe. And Da Vinci is diligent in thinking. I heard that when he was painting The Last Supper, all the characters in the painting were easily finished, except Jesus Christ, whose face, he felt, was impossible to paint, because Christ is not a human. How to paint his face? Guess how long he pondered on this? For 14 years. When he painted the face of Christ, the gloss of the painting had begun to fade. Only then did he draw the face.

What was the face he wanted to express, or what was “God” to Da Vinci? It was “necessity” for him. Da Vinci has pondered on the question for 14 years. I can only say that such artists are worthy of people’s most tremendous admiration, and they’re the greatest artists of mankind, who have done all these things.

In respect of artists, we just understand a little about their paintings. As far as I’m concerned, that’s not enough to understand the artists’ creation. When seeing a painting, most of us just appreciate it and learn about some of the painting skills. But if you really want to understand artists, the great artists in the history of mankind, I’m afraid that it’s not enough to just look at their paintings or visual art works.

This is the first point I want to talk about, that is, the crossover of the artists, the overflow and the bursting of the artists’ talent.

Let’s move on to the second point: in the work of an artist, how wide can the artistic scope be? What do I mean by talking about the scope of artists’ manoeuvring? Let me give you an example. In the summer, we may open a folded paper fan. Some people can open it to 90 degrees; some can open it at a smaller angle of 45 degrees; some people can open it wider to 180 degrees; others can open it to even 360 degrees, especially the creative artists. In fact, their artistic scope is very broad.

Comparing the two poets of the Tang Dynasty, Li Bai and Wang Wei are the great contemporary poets, but in terms of their artistic scope, Li’s is wider than Wang’s. Wang Wei is also a painter. Wang Wei was considered by Dong Qichang of the Ming Dynasty as the ancestor of Chinese literati painting. Wang Wei wrote frontier-style poetry in his early days, showing his heroism. But he impressed us most by his idyllic landscape poetry. “After fresh rain in mountains bare Autumn permeates evening air. Among pine-trees bright moonbeams peer; Over crystal stones flows water clear. Bamboo whisper of washer-maids; Lotus stirs when fishing boat wades. Though fragrant spring may pass away, still here’s the place for you to stay.” This is the typical style of Wang Wei from our impression. He painted a picture Wangchuan Villa, and also wrote a group of poems about Wangchuan Town. It’s said that his painting is now collected in Japan. The picture on the screen is said to be painted by Wang Wei; while some people think that this was imitated by a painter of the Song Dynasty. It’s a wild guess.

Wangchuan Villa

Li Bai is a contemporary of Wang Wei. Li isn’t a painter, but a calligrapher. This responds to the first point I mentioned, that is, artists’ scintillation of talent. Li’s calligraphy was seen by Huang Tingjian in the Song Dynasty, who passed such comment, “When I saw Li Bai’s manuscript, I found his calligraphy similar to his poem. In the Tang Dynasty, no one called Li Bai a great calligrapher. However, today his running script and cursive script are as good as that of his predecessors. Is he born to be a calligrapher, without training?” That’s his comment. Obviously, Li Bai’s calligraphy is overshadowed by his poetry. The example I gave just now—Ni Zan’s fame as a poet is also overshadowed by that as a painter. But in fact, such great poets and artists have many sides.

The only surviving calligraphy by Li Bai today is called Shangyang Platform Writing, in the Palace Museum. I’ve seen the original work in the flesh and I felt very lucky. When I saw Li’s calligraphy, my heart was beating fast, because I know that Huang Tingjian has also seen Li’s calligraphy before others. At that time, I’d feel that… I was standing in front of the exhibition, where there had been another person standing to see Li’s work—he might be Huang Tingjian. When he left, I stood here and appreciated Li’s work. It was hard to describe how I felt. When you look at Li Bai’s handwriting in the museum, you’ll feel that you’re so close to the Tang Dynasty. It’s no exaggeration to say that the Tang Dynasty seems to be yesterday. That’s the feeling.

Shangyang Platform Writing

Li Bai and Wang Wei are contemporary poets. Li showed broad-mindedness in his poetry. Li’s poles are in his poems. Generally, there’s an east and a west in terms of direction. He seemed to be still in the East Pole in the morning but in the West Pole in the evening. In the poems of Qu Yuan, there seems to be something similar, the feeling of running east and west. In Li Bai’s poetry, you’ll feel the vastness. Because we Chinese are so familiar with Li Bai’s poems that almost everyone can recite his poems. “A seafaring visitor will talk about Japan, Which waters and mists conceal beyond approach; But Yueh people talk about Heavenly Mother Mountain, Still seen through its varying depth of cloud. In a straight line to heaven, its summit enters heaven, Tops the five Holy Peaks, and casts a shadow through China. With the hundred-mile length of the Heavenly Terrace Range, which, just at this point, begins turning southeast....My heart and my dreams are in Wu and Yueh. And they cross Mirror Lake all night in the moon. And the moon lights my shadow and me to Yan River—With the hermitage of Xie still there and the monkeys calling clearly over ripples of green water.” This is Tianmu Mountain Ascended in a Dream by Li Bai.

We can recite the poem at a very young age, and you can feel the imagination of Li Bai. He has endless fantasies in his mind. I’m reminding you that Li is bold and unconstrained. But he also has another side. He wrote a short poem in his early years— “Dare not to speak loudly, in the fear of disturbing those in heaven.”

When you read his poem “Dare not to speak loudly,” that’s one of his poles; when you read “Come the queens of all the clouds, descending one by one”, that’s another pole. You can feel Li Bai’s artistic scope, which is wide from the sky to the ground. Of course, there’s a particular quality in his opening degree, something to do with his spiritual background, even though he’s familiar with Confucianism. For example, he said, “My ambition is to be like Confucius. With the writing style of the Spring and Autumn Period brush method, I’ll eliminate evil, support good, and let justice shine for a thousand years. I hope I can finish this mission just like the sages before me. I will never stop writing until Huolin comes.” This is what he wrote in Ancient Customs, in which he used an allusion of Confucius. The Spring and Autumn Period ended in the 14th year of Gong Ai of Lu. In the allusion, at that time, when Huolin, the auspicious animal, was captured, Confucius cried and stopped writing The Spring and Autumn Annals. Obviously, Li Bai is quite familiar with Confucianism.

Chen Yinque

But at the same time, he is deeply influenced by Taoism, which is known to many people. But where did the Taoist originate from? This is rarely discussed, but Chen Yinque, a great scholar in our country, believed that Taoism originated from the coastal area. On the seashore, there should be a scenic spot; there should be a similar one in a desert—that’s a mirage. The illusions you read in Li Bai’s poems are actually mirages. So most of our Chinese poets are related to the land.

Ancient Chinese poets were afraid of the sea because our culture is the Yellow River culture. Of course, archaeologists now believe that the Yangtze River basin culture is also a very important factor in the formation of the early Chinese nation. Our nation was generally said to originate from the Central Plains culture, mainly related to the Yellow River Basin. However, we can see that Li’s imagination has something to do with the ocean. He came from the Western Region, with a background in ethnic minorities. He strolled on the land of China, but his way of thinking was influenced by Taoism, which had originated from the coastal area, so he was also related to the mirage in the coastal area. If you don’t understand Li Bai from this perspective, you can’t understand what he is like as a person. Only by reciting his poem, “Beside my bed a pool of light—Is it hoarfrost on the ground?” can you have a well-round understanding of Li Bai. You have to understand his spiritual background. He is related to the ocean, so he said, “Sunny ocean half-way, holy cock-crow in space.” By ascending a mountain, you seem to see the sea in the distance. His temperament isn’t the same as that of many ancient Chinese poets. Li seems too deceptive like a liar, because his magnanimity and his aesthetics didn’t go with his time. It’s unknown where this person came from. But if we try to make interpretations, we may grasp something.

How to Read Tang Poetry

Li Bai himself isn’t a typical person from the Central Plains, but one from the Western Region. He didn’t fill an office like other scholars—I wrote it clearly in my book How to Read Tang Poetry—maybe he was forbidden to take the imperial examination by the laws in the Tang Dynasty. Thanks to his different life, we have such a poet in China, a poet with such a large artistic scope. You’ll feel his endless flow of creativity. When he was dying, he seemed to know what position he occupied in Chinese culture, and he wrote a poem entitled To Step on my Way. However, some scholars claim that it shouldn’t be called To Step on my Way, but To Step on my Way to Death. The characters were scribbled and thus mistaken.

He wrote in the poem, “The huge rook has flown all over the world; but now he’s powerless in the air.” That is, the rook is dying. There’s a scary line that no others dare to say, “The wind he leaves is strong yet to encourage generation after generation.” He flaps his wings and the wind blows, which will blow his later generations. I can find no better word to comment than a joking word—such a “liar”. “The wind he leaves is strong yet to encourage generation after generation.” It’s marvellous. No others dare to say so. We can see that Li Bai has a very wide artistic scope in writing. He overshadows who writes about little things: flowers and grass, our daily life, our tiny moods such as anger and longing, and makes us feel ashamed.

So I said Li Bai has a wide artistic scope, as vast as the universe. Some people may ask whether Du Fu has a wide artistic scope. Yes, he does. But the way he demonstrates his poetry is somewhat different from Li. In Du’s early poems, he wrote that “I must ascend the mountain’s crest, It dwarfs all peaks under feet.” You can feel his will and spirit. However, it’s hard to say that this “Du Fu” is the later one that we admire. One of the most important factors for why he could become what he was is the Anshi Rebellion, which occurred in 755 AD, and people who lived in that era were involved in. He became a minor official, but later drifted from place to place homeless and miserable. He became an advisor in the reign of Emperor Suzong in the Tang Dynasty, but he again offended the emperor. Later, he was appointed as a petty official in Huazhou. Some say that he abandoned the position, while others say he resigned. Anyway, he didn’t take the office.

There are various possible reasons for this. Some people say that it was the end of his term and he should change his term. Some scholars hold the opinion, while others say that he resigned and continued his vagrant life. He went from Gansu to Shaanxi, then to Sichuan; from Chengdu, Sichuan, to Fengjie, and at last to Hunan and Hubei. This is his route. The arrival of the Anshi Rebellion made Du Fu a great poet, who has a wide artistic scope. His expression of history and his experience of the time, that is, the historical experience and his personal experience can be combined in his poems. The greatest poem he wrote is of course the Ode to Autumn. It was written in Kuizhou, today’s Fengjie.

For example, many of our middle school students may have learnt his poem On the Height. “The wind so swift, the sky so wide, apes wail and cry; Water so clear and beach so white, birds wheel and fly. The boundless forest sheds its leaves shower by shower; The endless river rolls its waves hour after hour.” This is very different from Wang Wei’s poem, “Over crystal stone flows water clear”. At that time, Du Fu was seriously ill. He wrote this poem at the age of about 54. He lived to 58 years old. In terms of nominal age, he lived to 59; while in terms of full years, he lived to 58. At that time, one of his ears was deaf. He described himself in a line of poem, “My right arm is weak and one ear is deaf”. His teeth were almost gone; he had diabetes, which he called “Sima Changqing Disease” and there was something wrong with his lungs. Such a poor old man! In fact, he was younger than I am now. His writing came to a climax. It really strikes me every time I think about this.

Master Yan’s South Mountain Poetry on the 9th

Du Fu has a side that may interest artists, and visual artists. Du loves art and visual art. He mentioned many painters and calligraphers in his poems. Let’s look at the calligraphy Master Yan’s South Mountain Poetry on the 9th. Some people claim that it’s the only hand-drawing rubbing of Du; while others doubt that and say it’s fake. Mr. Qi Gong said that this was forged by people in the Song Dynasty, at least it was carved out after being copied by them. This is what he thought. But anyway, we can more or less feel Du’s art taste. We can see that his handwriting is quite thin. He himself wrote in a poem, “Only thin and hard handwriting can be superb.” He liked thin and hard calligraphy.

Contemporary with him, there was a big man who recently had a big exhibition in Japan. It’s Yan Zhenqing. Have you noticed that few will mention Du Fu when talking about Yan Zhenqing and vice versa? But in fact, they knew each other. This is what Yan’s handwriting is like. His temperament is very different from Du’s. Assume that this is Du’s calligraphy, or one that is close to the characteristics of “thin, hard and superb” by him; while that’s what Yan’s handwriting is like. They were both officials during the reign of Emperor Suzong in the Tang Dynasty. Yan was a higher-ranking official, while Du is a lower-ranking one, but they must have met each other. However, they had different tastes. Du’s art taste is closer to that of the early Tang Dynasty. He liked Xue Ji’s style. This is Xue’s calligraphy, also very thin. Du didn’t like anything fat; while he liked thin art. So in painting, he didn’t like depiction of anything fat. Although we know that the women in the Tang Dynasty, from the fat Tang Sancai dolls in the museum, were all fat. It’s estimated that Du didn’t like them. I guess the Du’s family were thin. He liked calligraphy like Xue’s, which he mentioned in his poems.

He has written about many calligraphers and painters. He wrote a poem for Cao Ba, a very important painter of the Tang Dynasty, who was a descendant of Cao Cao. When Du Fu was in Sichuan, he was acquainted with Cao Ba and wrote a poem to him. He had a student named Han Gan, who was also very famous in the history of art. Horse paintings of Han are now collected in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in the United States. This is Night-Shining White. In Du’s poem to Cao, he didn’t like Han and wrote a line, “Han only draws the flesh without bones,” saying that he only drew the flesh of the horse, but there weren’t bones. Du wrote a poem The Thin Horse, from which you’ll know that Du likes thin, and the shape with bones. He didn’t like fat horses. He didn’t like such things. We can understand Du Fu’s art taste.

I just mentioned that Du Fu had some friends as painters, among which there was a big painter named Wei Yan. He was also a good friend of Du. Who was his relative? After the Anshi Rebellion, there was another poet in the Tang Dynasty. Of course, it wasn’t so great, but it was also very important. It was Wei Yingwu. Wei Yan was a relative of Wei Yingwu. Maybe they were cousins.

Wei Yan and Du Fu were good friends. In the history of Chinese art, Wei was a great painter. In the Song Dynasty, Li Gonglin imitated Wei’s Wrangler Map. How close they were! The painting is in the Palace Museum. This is Li’s imitation, while Wei’s original one has been lost.

Du Fu and Wei Yan were good friends. When Wei was about to leave Chengdu, he painted the horse on the wall of Du’s cottage. We didn’t know what it was like. But Du later specially mentioned it in his poem. Du, who had a very close relationship with painters, knew almost all painters of his time.

Since I mainly talk about visual art today, I mentioned the relationship between Du Fu and visual art, but I will leave the rest. I talked about Du’s artistic scope and his writing, which are different from Li Bai’s. His style of imagination is the Central-Plains-originating, the Yellow-River-Basin-originating, and soil-related, but how did he get such a wide artistic scope? He was born with this possibility, and his life experience helped, such as the Anshi Rebellion, so in his poems, he wrote a lot that wasn’t so poetic. During his vagabondage, his daughter was hungry. He wrote in a poem, “My hungry dull girl bites me.” The dull daughter was so hungry that she bit her dad. Such description can never be accepted by the art crowd and the chic.

So you’ll feel that the relationship between Du Fu and people of his time, and his writing as a way to participate in history are still very desirable for us today.

The last thing I want to say is that we’ve seen such an artistic scope in Du Fu, as well as the legacy in the history of literature. If we then reflect on ourselves, we’ll ask ourselves a question: Is our work, our writing and artistic practice, commensurate with our own times?

And if you want to be commensurate with the era, how much should your scope in artistic manoeuvring be? This is my last question. That’s all! Thank you.