Xu Bing (hereinafter referred to as Xu): Thank you for coming today. I’m sorry for being late, I made some rearrangements here after I arrived. I hope we can talk freely. Everyone can ask any question, and we can have a discussion together. Let’s get started. Hurry up. The floor is open if anyone has a question.

Female (hereinafter referred to as F)1:

Hi, Professor. Xu. I have a question. From your early printmaking to the later “Ghost Pounding the Wall”, “Book from the Sky”, “Book from the Ground”, “Phoenix”, and then to the recent film, a dramatic shift has taken place in the art medium you adopted. The span of this transformation is enormous, and the use of media is amazing. Because it was first carved out of wood, and then in an extraordinary method of artistic creation. My question is: do you think your medium is necessary for your rich thoughts? Or what role does the media play in your artistic creation? Thank you.

Xu: Fundamentally speaking, I pay attention to the form and style instead of materials in my creation. I’ve said this many times. Actually, it’s become boring. Why? Because I think what matters to artists is that we are clear about the art, that is, about what we are doing as artists—whether we want to create a style, or express ideas that haven’t been expressed in the past. The former one represents one way; while the latter represents another. What’s art to me? In fact, art is something that people have never said before and that you should express clearly and fully. Therefore, you have to find a new way to speak. What’s the new way to speak for artists? That’s a new expression. It’s not presented through language; but by a material. It’s the final step for artists in finishing a work. To be honest, it’s just a matter of whether you’ve found a material, a way or even a space that can be used to speak what has never been said before. To express this well, you can’t borrow the vocabulary directly from the past masters. It’s simple. Why? Because what you say has never been said before. It should be said right now.

Xu Bing's Drawing of David when he studied at China Central Academy of Fine arts in 1978

In the past, the masters created those languages, and said what they had to say at that time. They had such a relationship. Another thing is that the language I used in the past can’t be borrowed directly. Because I have different understandings of society at the age of 20 and 30, the attitudes towards the world must be different from now. I did a lot of prints, woodcut prints in the past. Can the language at that time, which was created by myself, be used directly to express the current situation? In fact the answer is no, because I’m not what I was at that time, and the world is not what the world was at that time. Problems then were different.

Xu Bing, Book from the Sky

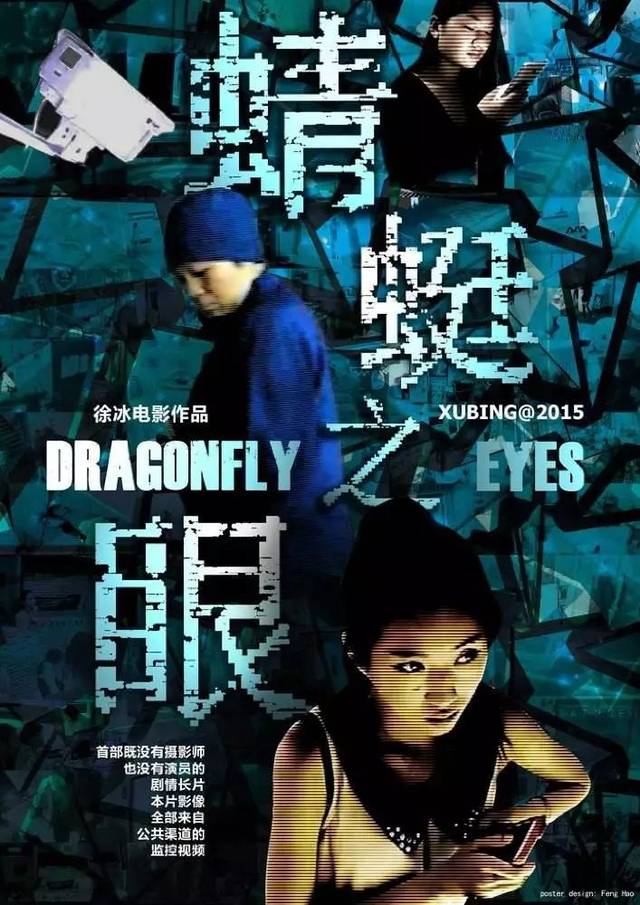

For example, a lot of critics in the West can see at a glance the relationship between “Dragonfly Eyes” and “Book from the Sky”: many of the techniques in “Dragonfly Eyes” are inherited from “Book from the Sky”. Because in the end they find that the artist actually likes to create a fact with mammoth work, which is illusory, or never exists. Many people may find my earliest understanding of the core concept of printmaking in the “Dragonfly Eyes”. Why? For example, what exactly is printmaking? It isn’t a woodcut, a copperplate, nor a form of painting. But what is it? What’s its core concept? When I was a graduate student, I was thinking about that. Finally, I found that the actual core of printmaking is the pluralism and its prescriptive imprint.

Poster of Xu Bing, Dragonfly Eyes

It is the two core concepts that make printmaking irreplaceable by oil paintings, Chinese paintings or any other paintings. Therefore, the type of print can exist. As for the pluralism, it enriches the materials, this is widespread all over the world, so that I can get loads of monitoring material. All those are actually about pluralism. What about the prescriptive imprint? To put it simply, an oil painting is also an imprint, a fluid imprint; while a print is a prescriptive imprint. The fluid imprint is related to our personal emotions and physical state at any time; while printmaking is indirect. Let’s go deeper into the concept of printmaking. In fact, I think printmaking has a particularly striking feature, which I did not realize until now—the indirectness of expression. The indirectness of expression is actually the same as pluralism, with a contemporary consciousness. Almost all of us express through indirectness. This is a very significant topic in our life and in our relationship with the whole world today, on which we must reflect. For example, everyone has a mobile phone, on which we all give indirect expressions, and announce to the world who we are. And I can communicate with someone and give a notice in an indirect way on WeChat, even if we are sitting at a table face to face. The indirectness of expression is conveyed through an intermediate medium. A print that is engraved on a woodblock and then transferred to another carrier demonstrates the indirectness of expression.

In the end, you find printmaking becomes increasingly contemporary. All fields on the cutting edge are actually related to pluralism and indirectness of expression. This is my answer to your question. That is to say, your works can always change in language expression, but with an internal propulsion. The root of it is the propulsion of thinking.

Male: Hi, Professor Xu, I have a question. Technology has exerted a great impact on the development of our modern life, while our perception is limited. In the face of so many huge technological systems, how can we as artists integrate these things in the process of creation? How can we as individuals with weak perception perceive all these things?

Xu: In general, each of us, each physical person, must face a subversive change in the whole world. As artists, we believe that artists, with the talent to create and express themselves, can’t be replaced. As far as I’m concerned, the so-called contemporary art, or the creativity of the contemporary artists, is far less than social creativity. Science and technology change our life and way of thinking with new thoughts of energy and power. We shouldn’t value art too much, thinking in that the field is the most creative. On the contrary, it’s probably the least creative field, or it’s a field that is just seemingly creative on the surface.

Exhibition View of “Xu Bing Thought and Method” in July, 2018 (Photo Courtesy of UCCA)

I do feel that artists are trying to battle with this massive technology. They have the strength of art—I mean, the strength of thought, not the strength of techniques and technology. What’s the strength, or what’s the core part of your works? As long as it’s inspiring, beyond the field of technology, I think it can be used to battle with technology. The point is to throw things off balance by getting 51%. Only if your artistic core concept is worth the 1%, can your work be of little value; if not, then your work is worthless. In fact, many of the so-called art and technology exhibitions today, most of which I think are science and technology exhibitions, have a problem: everyone does enjoy these exhibitions just like this one, which is almost an exhibition of games and toys. They find it very interesting to see the movable stuff.

Actually, it is an exhibition with no political or social consideration and no thought. So the problem is whether we have the ability to battle with technology. Without this, your art will soon be outdated. Why? Because new technology may come out next month or half a year later, very soon. After the new technology comes out, your so-called “new art” will become old art, or even nothing, worthless. This is the relationship between art and technology.

F3: Hello, Professor Xu. Since I’m graduating from my postgraduate program this year, I’d like to ask you two questions concerning graduation. The first question is: what should be maintained in our artistic creation for graduation? That is to say, it concerns the simplicity of artistic creation as well as the reference you just mentioned, and a more penetrating issue in creative ideas. That’s the first question.

Xu: Indeed, it’s also a question worth discussing. Let’s take this graduation exhibition as an example. In this exhibition, I find that many students—creators of the works— understand little about art, which in fact, is still the core issue: what is the artistic creation? Many works are a bit fancy and interesting. But I don’t think it’s the most important thing for us as artists. What we should consider is how to express our thoughts and core concepts in the most effective way. I think the first thing to do is judge whether a work is worth producing. In fact, it is really difficult to figure out what is worth producing, and what is not. As for me, I don’t know why some people make such a great effort to create works of art, which aren’t worth the effort. Why? Because it takes a long time, but produces no new concepts. Why are some works worth producing? Because if you are fully expressed in your work, it may bring a new concept or a value to human civilization. There’s a premise: you have to show the concept is strong and solid enough; and reasons suffice to show it will simplify your work.

It is because you’re confident about what I’m going to say that the way I talk on the surface can be very clear and concise. Another problem is that some pretend to conduct very in-depth academic research and preparation before they create the works. They may do a lot of social investigations—when I was a student, I also did social surveys, asking thousands of people what the meaning of life is, or did research on a wall in a small town. I could have done it for a lifetime and could have found a myriad of different phenomena on the wall—however, when they put the final work on show, they tend to feel too good about themselves, because they have spent too much time thoroughly carrying out their research project.

I’d say such works are created in a lazy and stereotyped way. They haven’t improved their thinking ability. What is really difficult is not to collect something in a small town, but to make progress in thinking ability. No matter how little the progress is, it’s marvellous and worthwhile. It’s the same with excellent writing and artistic creation. Their creators are really great because they can successfully express something in the most succinct way, without quoting all kinds of western terms or academic terms.

The experience to purify a thing to its simplest form is accumulated by generation after generation. It’s most inspiring when I watched the Japanese drama Noh at the National Center for the Performing Arts. I had a profound experience after that. I think the drama Noh is really great. It’s actually even more concise than Beijing Opera where the gestures are all stylized and quite concise, and the drama has been simplified to the extreme. At the end of the performance, the actors walk down the stage, facing the audience, never turning back. This is a special technique. I’m wondering why they do that. The performance is hoped to be the simplest without even a redundant movement such as turning back. That’s it.

There’s another feature of Noh: every performer wears a mask, because the masks are chosen and their concepts and meanings are all stipulated, while the faces of people in reality are complex and secular. A lot of messy things are added to the drama, such a lofty drama. I still remember I later worked with animals. In fact, I found that working with animals can make your work very pure and simple, because animals don’t create so many personal distractions and thoughts that complicate your performance or work. It’s particularly remarkable in Noh that every performer wears a mask and has a small box which should be opened before he/she takes the stage. And he/she says something to the mask. Guess what he/she says? He/she says, “It is high time that I should wear you and play the role.” It’s such a ceremony, where he/she says to the mask that he/she will take its role. It means that he/she isn’t playing the role of the worldly flesh, but of you, the mask. Such simplicity makes Noh stand out compared to our contemporary art, or compared to the the various drama series with complicated lines.

F3: The second question is how to further advance artistic creation at this stage. That is to say, as graduates, how can we achieve the simplicity, or how can we develop our personal creation more effectively?

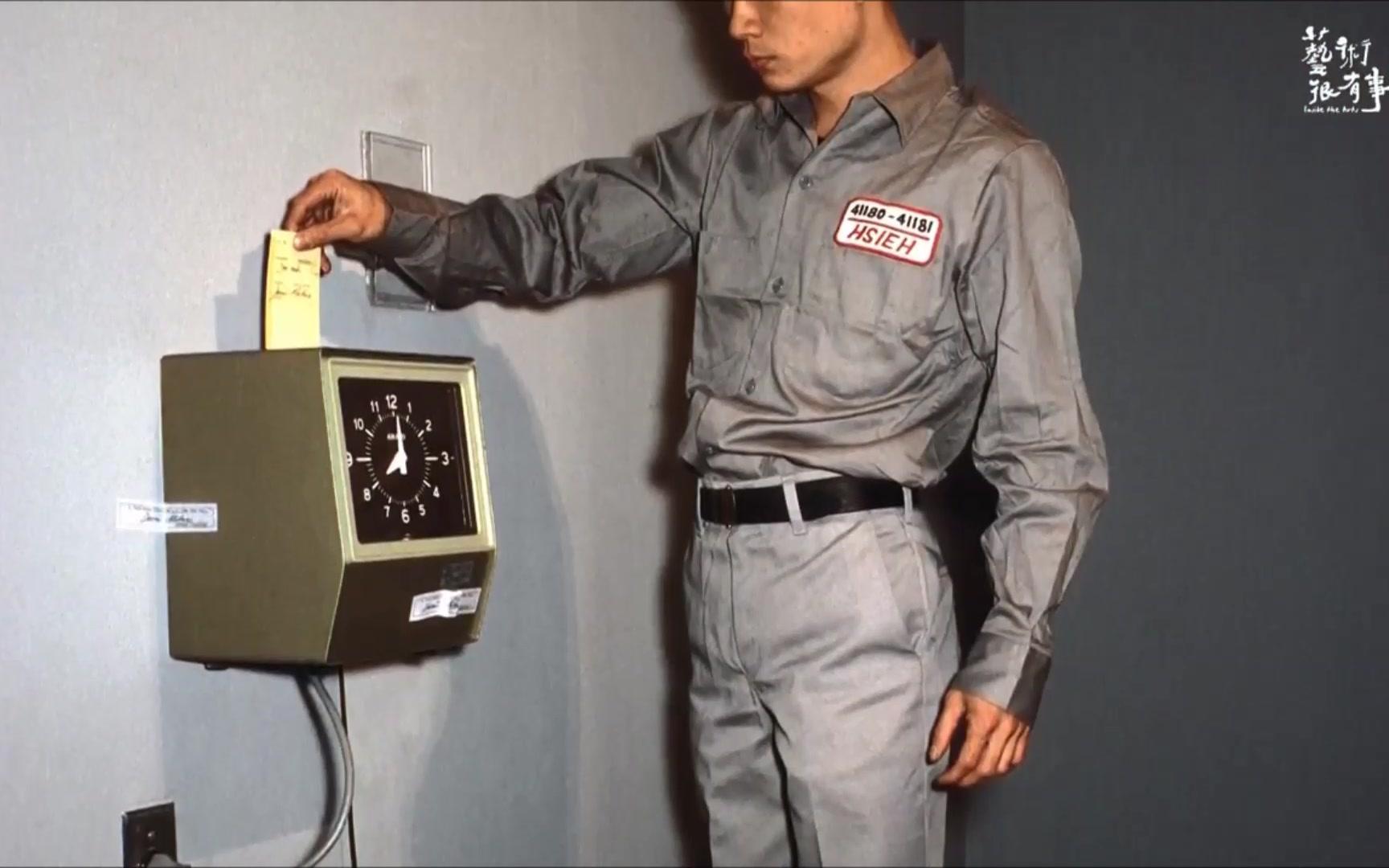

Xu: To put it simply, as I said in the past, you shouldn’t care too much about your art work. You should know how to absorb the energy of society. It’s easy to understand. The fresh blood of the art system isn’t produced in the system itself. What’s there in this system is already there, and what the system lacks must be something outside the system. Let me give you an example. One of my friends is also a very important artist. Xie Deqing, a Taiwanese artist living in the US. All of us may know his works. Personally, I think he’s actually a very great artist.

Xie Deqing (Tehching Hsieh), One Year Performance 1978-1979 (Cage Piece)

There’s no doubt that his work itself is extremely valuable to the advancement of human civilization, or of human limits. He always has a problem that he’s too avant-garde to find a place for him in the history of contemporary art. Some of his works, for example, were created on a stage for a year; he kept a daily record of allowing himself no more than one hour of sleep for an entire year; and he lived in the wild for a year without coming into the house or under the eaves. I particularly like the part where he and Linda were tied together with a rope, but keeping a distance of maybe two or three meters, which you might know. I got acquainted with him, and learned that since he finished those four works, basically he has done very little. But he explained he was making another behavioral performance where he did nothing over seven years. Of course, this is an interesting explanation. We’ve been on the phone a lot since we first met, even before we met. In fact, he’s always been looking for what else is possible to present more progressive works than the previous four ones. Since he’s demanding, he’s not going to do it without pushing a little bit.

Xie Deqing (Tehching Hsieh), One Year Performance 1980 -1981 (Time Clock Piece)

Xie Deqing (Tehching Hsieh), One Year Performance 1981–1982 (Outdoor Piece)

Xie Deqing (Tehching Hsieh), One Year Performance 1983—1984 (Rope Piece)

Once he and I went downtown in New York to get a pizza. That pizza place was supposed to be the best in New York, so there was a long queue. In front of us was the Twin Towers. We chatted, saw the towers and then talked about it. I said, “I was at the University of Wisconsin-Madison when I came to US for the first time, there was an issue in the field of computer science, instead of in the field of art, which a young man did. I really wanted to share with you what he did. Online shopping just started at that time. The young man who was probably a high school student himself—maybe a new graduate— liked computers very much. His mother said, ‘You wasted all your time playing on the computer. Can you live on this?’ As expected, he said he could. At that time, when online shopping was a new thing, he promised that all his daily necessities would be ordered online and that he wouldn’t go out for a whole year. Later, he really went on to fulfill his promise. Many companies, especially those related to the Internet, found it very interesting and thus invested in him. They installed all kinds of cameras and tracked him. At last, he survived staying in his house for the whole year. I realized then that the young man’s behavior, from the perspective of behavioral art, was the most central, experimental and worthwhile behavioral art, much more worthwhile than any other shows, nakedness or rolling, though he didn’t mean to perform behavioral art.” I told all that to Xie later.

Xie, waited in line without saying a word, was thinking about it, and after a long time, he said, “We were equal.” He meant that he and the young man were equal, because he knew the value of the behavior of that young man. Imagine that if the behavior of this young man were carried out by Xie after more than 20 years, Xie would be even more admirable. Why is his behavior so admirable? Because what he discussed, experimented, and faced is a very significant project that we humans will face. Of course, each generation of artists have their own matters and perspectives of thinking. But it can be said that our generation of artists or Xie’s generation of artists may not pay too much attention to the resistance and subversion of the art system itself, and aren’t able to acquire intellectual energy for creation from the problems that may be encountered in the existence as a human, or the future.

So how can we advance? Or what should I do after graduation? What if my work is great enough, or my teacher has already given me the best rating? The real advancement is indeed not in our art knowledge itself, but beyond this, there are other possibilities, because beyond that, there are too many things unknown and too much food for thought.

F3: Professor Xu, I have a hypothesis. If, in the near future, our common method of communicating is to use memes to replace English and become a universal language, I can say nothing to people. Chats on WeChat or discussions on paper can be conducted through memes, which is probably better than the text because like other commonly-known symbols, they’re more suitable for communication. This is my hypothesis.

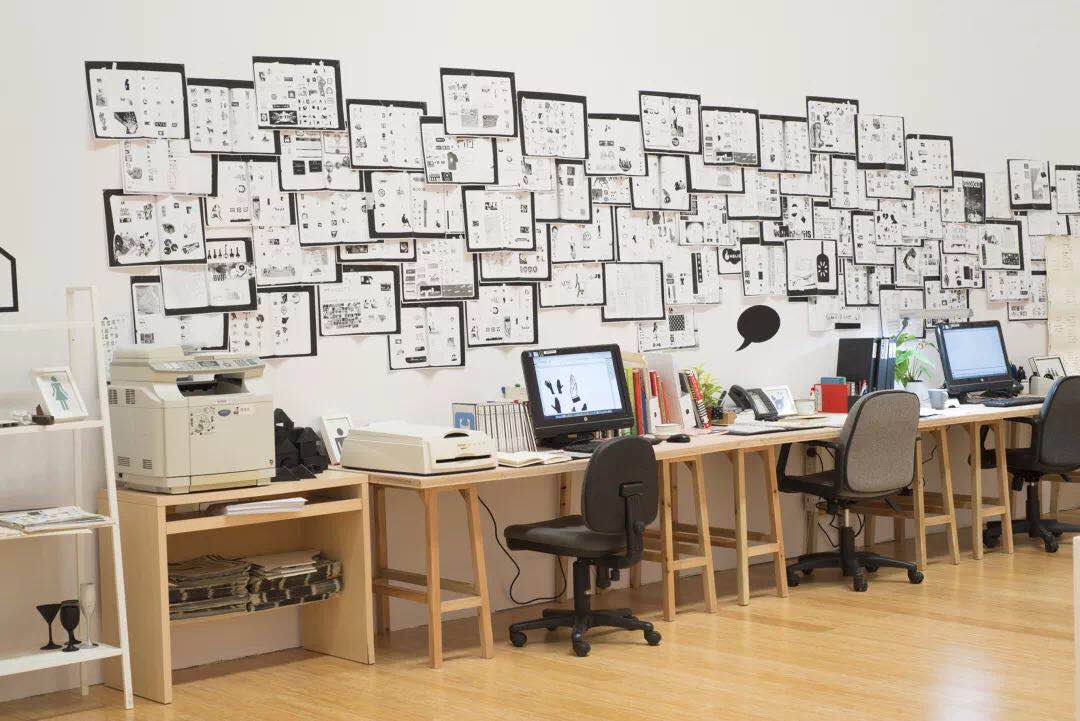

Xu: You have a good and bold idea. It’s actually interesting, and there’s correlation with my “Book from the Ground”. “Book from the Ground” was finished, thanks to the rapid growth in recent years of the so-called memes, or the denotative symbols. So, when I had the conception to write a book with these things at first, I couldn’t do it, because there weren’t many memes—there was only one set at that time. Later, it was finished, because the memes developed too fast, with hundreds of thousands of sets. This is a bit like the material used in “Dragonfly Eyes”. In fact, I especially like to use materials that are growing and not mature.

Memes have grown rapidly. Their ability to express has developed so fast that they’ve gone far beyond our plans and imagination. In fact, memes can express much that our traditional text can’t. For example, I chat with someone on WeChat, and it’s quite late. Both of us hesitate and feel embarrassed to send the text message saying “I wanna sleep”. Then neither of us need to say that in words. Instead, one can send an emoji of moon. Anyone who knows the memes, will see that it’s time to stop chatting, or that he/she doesn’t want to talk to me any longer. This is the special function of the expression of memes, which the traditional text lacks. Here’s another example. Some people don’t like to say “I love you”, but with memes, they can mess around and dare to say that to anyone. Is this called “love with memes”? That is, I can send it to 100 people at the same time, meaning I love them all. Such function is unique to memes. It has different connotations and denotation from those of the words “I love you” in the past.

I’ve been playing with the language for so many years. Later, I realized that the maturity of a writing system and the improvement of its usage aren’t in the system itself; but instead, in the ability of mutual complementation between the user and the system in long-term use. Which one do you think is more expressive: the sign language or the memes and my “Book from the Ground”?

F3: It’s difficult to answer. It depends on different contexts. In face-to-face communication, if we can’t use words, then it’s of course more convenient to use sign language. But if I communicate with you on the Internet, memes might be more concise. We might think that your “Book from the Ground” is more like a long story unfolding in a clearer way.

Xu: Yes, indeed. When “Book from the Ground” just came out, everyone was actually not used to reading it. But now more and more people, especially young people and children, can read it very fast. In the past, in a family, the parents explain the traditional text for the children. Now things are different. It is the children who read and explain for the parents, because the former can read very fast. After our generation of people who know the traditional words have all died, those who grow up with memes, or who grow up reading “Book from the Ground”, may find them more convenient. This is what I mean by saying that the maturity of a language isn’t a matter of the language itself. So you see, the functions and ability of expression of the memes have greatly improved.

Xu Bing, Book from the Ground, 2014; Mixed media; Dimensions variable; Collection of the artist

F4: Hello, Professor Xu. I have a question. I’ve noticed that many of your works are constructed with relatively large workloads, such as the early “Book from the Sky” “The Character of Characters” to the recent “Dragonfly Eyes”. It seems that you value the workloads, even those behind the works, most of which have supported the value, status and weight of your works. My question is: what do you think about the relationship between workloads and works? Do you mean to do that? Just now you mentioned the relationship between art and technology, with the former struggling for the 1%. I’m wondering whether the workloads accumulated help to gain the 1%. Thank you.

Xu: This has something to do with one’s personality and attitude towards art. Actually, I like to do something that others can’t. If everyone can do it, then it isn’t worthwhile for me to do it. I bear this in mind. As long as you’re sure that something is worth doing, you must do it very seriously. Because there’s something that requires a serious attitude, and then the strength of the art is in the transition. Just like in “Book from the Sky”, if you wrote one or two fake words, or even a whole text of fake words, it wouldn’t make sense. However, if you use fake words, carve them out, and then handprint them out to be a book, the strength of the philosophy and public opinion contained in it would increase. In fact, it is hard for others to believe that there’s actually a person who has spent several years doing something that he said nothing about. It mismatches the perspective of thinking and understanding of normal people, which, I think is actually very important. So, some of my works seem to be quite simple, but in fact the workload is huge. In fact, whether a student who graduates from the academies of fine arts is qualified or not rests on one thing—to be exacting. For example, someone who polishes a piece of wood may find it OK to do almost 70%; while another one may think that he/she has to polish it to 100% perfect. They’re different.

In fact, little difference may decide superior or inferior works of art. Those with a little extra effort may stand out.

F5: Hello, professor Xu. I have a question about art in the AI era, that is, technical aesthetics. New techniques and technology produce new standards of art, literature and perception. Then they’ll enable the computer to create art, and before that day finally arrives, the computer gives us enough opportunities to search for who we are, and then how we should define new standards, new cognitive ways and a new perspective. Life will cause imbalances in standards. Then, how should we derive new methods from new consciousness? Thank you.

Xu: Yes, indeed. Do you know what I like to do? That is, if I’m doing something, like contemporary art works, I’d reflect on the defects of contemporary art. You raised a good question. I think all human beings are facing a new situation, which may arrive after a long time, or which may come sooner. It seems that it’s getting faster. When the era comes, all we’re discussing today will be invalid and worthless. Just like our literature in the past—such great literature or art—in the face of that era, it became useless. Why? Let me show you by giving an example. AI can finally produce a lot of AI men for us, who are very different from us natural humans. People must face an era in which natural humans and AI men overlap, though our generation may miss the era. Sometime later, natural human beings will be gone. Why? Definitely. Because the natural humans are short, ugly, not smart, and subject to illness and a short life, they must be discriminated against, or must be inferior. That’s for sure.

In almost all of our fields, we’re beginning to be challenged, and we’re slowly becoming ineffective and idle. Boundaries are becoming blurred, including those between films, those between human beings and those between truth and fiction; how will we define laws, monitoring, the portrait rights and so on? Everything we discuss today, before that era comes, must be ineffective, useless, and worthless, because an era has problems of the era itself.

Xu Bing worked on Book from the Ground, Photo Courtesy of the artist and Photo by Xue Feng

F6: The show is about to end. Thanks to “Insights into Art”, everyone can take this opportunity to be with you, I’d like to ask a few questions. The handsome guy beside me has been saying, “Keep talking! Don’t stop!” We feel really lucky. Thanks for this event. You’re an artist as well as an art educator, so what do you think about these two jobs, and which one do you prefer, in terms of the influence, meaning, or personal preferences? What do you think of their relationship? Since I’m an art educator of children, I think art education for them is also exploring the broad concept and doing some training on thinking. But I think, in the world of children, you’ll find yourself powerless to do something, because you’re not a child.

Xu: For example, I’m an artist. I like creating; while I don’t like education that much. But I like to discuss art with young people, such as my doctoral students and graduate students. We’re actually discussing what art is. We did do something weird. Those that need “unknown” materials are actually worth doing. When done, they’ll be handed in to professors like Li Jun, because I heard the other day that he has a work entitled “Insights into the Insights into Art”. In fact, what’s their mission? That is, to gain insights into our works. They’re struggling, because what we provide can’t be explained with ready-made knowledge. Such works are good. And he has to follow and sort out an artist’s works, study the artist as well as his/her social relationship, and finally sum up new concepts. If a work has a new concept for the human cultural world, we actually make contributions to humans through this work. The service for children, or education for children, is another thing though, the core lies in this.

What’s the ultimate task for artists? I’ve always claimed that the duty of artists is to complete what you just said, to find a specific kind of artistic expression for what you want to say. You can be a great thinker, but art history won’t heed you. If you haven’t finished this part of the artists’ work, though you have a lot of thoughts, then art history won’t care about you. That’s it. Of course, the art education for children as you said is particularly tough. To some extent, there’s something very special in children, which however disappears among us adults. I believe children are endowed with something like exceptional functions and perception. But as the children grow up, our civilization and rules keep taking its toll on them, and ultimately makes them like us. That’s it.

Therefore, a Belgian children psychologist said something impressive to me. He said that the purpose of our human life is to find out what we’ve lost. And you’ve noticed that there was a time when I really wanted to sort out children’s words, which were really wonderful. In whatever fields, such as literary descriptions, philosophical thoughts, and so on, children’s words are at least hit the nail on the head. For example, one day when I went to pick up my daughter after school, she asked me the name of a tree. I said, “I don’t know. Daddy has to go home and look up what it is. Everything’s in the book.” She suddenly said, “Nothing’s in books except words.” Isn’t that exactly the theme of “Book from the Sky”? I’ve put great efforts into it. It’s so popular, and has received all kinds of comments from critics. Another example is Zhang Huan’s son. Zhang Huan once walked in front of his son, who walked particularly slowly behind. Later, Zhang Huan asked what was wrong with him. He said that he got a lot of sand in his leg and the leg is getting numb. It’s a wonderful literary description. So, this involves an issue of art education, what academies of fine arts give us, and whether we have the ability to protect the most valuable part of ourselves. A good teacher helps one to find the treasure in him/her and then to find a hole for him/her to dig. You have to help find the right place. As for how he/she digs it, it’s his/her own business. Ok, that’s all.

Xu: Thank you.