Following the lecture entitled “Dating and Identification of Chinese Painting & Calligraphy – Paintings of the Yuan Dynasty” given by the art historian Joan Stanley-Baker on October 28, Joan Stanley-Baker continued to deliver a lecture entitled “Wang Meng’s 'Dwelling in the Qingbian Mountains' and Other Works under His Name” on October 29. While the first lecture on October 28 presented us with a methodological basis for Joan Stanley-Baker’s dating and identification, the second lecture was an in-depth discussion on the case study. In the lecture, Joan Stanley-Baker started from the treatment of the spatial relations using intensive brushwork, to analyze the relationship between the original work of Wang Meng and the “anecdotal Wang Meng’s works”. Both lectures attracted wide attention from professional scholars and art history lovers.

“Dwelling in the Qingbian Mountains”: Only Half of an Authentic Work by Wang Meng SurvivesAt the beginning of the lecture, Joan Stanley-Baker directly proposed her opinion: few authentic works by the four masters of Yuan Dynasty are handed down, while only half of “Dwelling in the Qingbian Mountains” (1366) by Wang Meng (1308-1385) is an authentic piece among the “anecdotal Wang Meng’s works”, so it is worthy of further study. How to determine “Dwelling in the Qingbian Mountains” a work of the Yuan Dynasty, and a work created by Wang Meng?

Starting from two surviving Chinese paintings of the 8th-century landscape paintings (a piece drawn on the south wall of the main chamber of Cave 103 at Mogao Grottoes in Dunhuang, and another piece drawn on the Fengsufangran Mother-of-Pearl Inlay Chinese Luth in the collection of Shosoin of Japan), Joan Stanley-Baker explored the basic features of the cosmological view and landscape paintings of the ancient artists: there are high mountains, distant mountains, water, and they allow us to feel the temperature, humidity and wind. It is also an important criterion for her identification of ancient Chinese landscape painting. Joan Stanley-Baker believes that landscape painting developed from Tang to Yuan, and a realistic habit has been formed. The landscape paintings present a clear spatial distance between three perspectives. During the lecture, she showed us a group of Chinese landscape paintings scattered in various museums. The group of Chinese landscape paintings that came from the 980s, the 1030s, the 1280s and the 1350s, showed a strong sense of the times. In addition, she also led us to observe the changes of visual focus in the recursive landscape paintings after the finishing of these paintings: the position of visual focus in landscape paintings of Tang and Yuan Dynasties gradually moved from the top of the screen to the bottom. Seen from the context of time, the position of the visual focus of “Dwelling in the Qingbian Mountains” was of the characteristics of Yuan landscape. “Dwelling in the Qingbian Mountains” showcases clear layers and bright space, while the distance between the front and latter mountains and the control of the retreat are consistent with the spatial extension model of the Yuan Dynasty, and it also inherits the structure and form of landscape painting of the Song and Yuan Dynasties. However, how to determine a landscape of the Yuan Dynasty created by Wang Meng? In the opinion of Joan Stanley-Baker, Wang Meng was the most skillful among the literati painters, and it was obvious that “Dwelling in the Qingbian Mountains” was influenced by the appearance of Guo Xi’s landscape paintings, but the brush & ink of the painting is rich, and unique in style. Wang Meng saw many precious collections of calligraphy and paintings in his grandfather Zhao Mengfu’s house, and even copied paintings of different appearances before he drew a masterpiece such as the “Dwelling in the Qingbian Mountains”. In addition, Joan Stanley-Baker discovered that the writing rhythm of the inscription of “Dwelling in the Qingbian Mountains” was similar to the inscription of the “Double Sheep” which was identified as an authentic piece of Zhao Mengfu by the speaker, so that, it can be regarded as the authentic piece by Wang Meng.

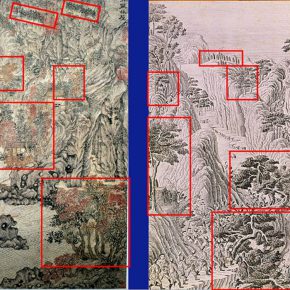

In the display of the above Chinese landscape paintings in successive dynasties, Joan Stanley-Baker also found that the size of “Dwelling in the Qingbian Mountains” was different from other works, and she believed that the two sides of the work might have been cut. She further compared the “Dwelling in the Qingbian Mountains” with the other authentic literati paintings of the Yuan dynasty, such as “Fisherman Figure” (1342) by Wu Zhen (1280-1354) and “Rongxi Room Figure” (1372) by Ni Zan (1301-1374), to confirm the existence of this issue. In 1982, Joan Stanley-Baker personally went to the Shanghai Museum to observe and took photos of “Dwelling in the Qingbian Mountains”. She found that there was a problem of different fonts placed in the inscription on the top right of the screen, “April, the 26th Year of Zhizheng, the Yellow Crane Hermit Wang Shuming Drew the Dwelling in the Qingbian Mountains”, and it was suspected that there were missing words. So that, she identified that the existing “Dwelling in the Qingbian Mountains” had been cut, namely it is “half” of the authentic piece.

What is the original appearance of “Dwelling in the Qingbian Mountains”? Did anyone see it before it was cut? Through comparing Wang Meng’s “Summer Mountain Residence Figure” (1368) with “Autumn Mountain with a Buddhist Temple Figure” (1362) as well as the authentic piece of “Lu Mountain Figure”(1467)by Shen Zhou (1427-1509), to discuss the original appearance of “Dwelling in the Qingbian Mountains”. Using the depth of the horizon in the paintings, she speculated that the horizon on the right side of “Summer Mountain Residence Figure” and “Autumn Mountain with a Buddhist Temple Figure” was longer than the “Dwelling in the Qingbian Mountains”, and it might be that the original appearance on the right side of the painting had been cut. And she then speculated that the “Autumn Forests and Deep Valleys” and “Autumn Mountain Humble Cottage Figure” (1372), was presumed to be the original appearance on the left side of the “Dwelling in the Qingbian Mountains” which has been cut, depending on Wang Meng who often portrays lakeshores and water on the left side of the works. Joan Stanley-Baker thought that Shen Zhou might never have seen the authentic piece of “Dwelling in the Qingbian Mountains”, but at least he would have seen works which were similar to the “Dwelling in the Qingbian Mountains” in the composition, space and brush & ink, passed down by people of the Yuan Dynasty.

For the other works under the name of Wang Meng, Joan Stanley-Baker made a comparison of the structure, shape, and ink & wash, etc. between different paintings and made her own identification. Except for the “Dwelling in the Qingbian Mountains”, all the works including “Summer Mountain Residence Figure”, “Autumn Mountain with a Buddhist Temple Figure”, “Autumn Forests and Deep Valleys” and “Autumn Mountain Humble Cottage Figure”, “Ju Ou Woods and Houses”, etc., were not authentic pieces of Wang Meng. Nevertheless, she believed that although these works were not authentic pieces, and they missed the real names of the creators, they were actually created and exist, so they were the objects of our study of the history of art. How to conduct the identification of painting? Joan Stanley-Baker believed that the first step of identification was to carefully be in contact with the painting, using the skin to feel every brushstroke of the screen, instead of reading the literature in advance, or one would form presupposed thoughts of the new discovered material depending on the literature which has been read, affecting the conclusion of identification.

Art History is Not a Master’s History: Survival Works Reflect the Style of the TimesAfter the end of the lecture, Joan Stanley-Baker and Shao Yan, Associate Professor of CAFA had a dialogue. Shao Yan bluntly said Joan Stanley-Baker’s way of identification was too harsh. She believed that the four masters of Yuan Dynasty took a lot of time during their lifetime to create, and finish a large number of works. And the majority of paintings were collected by civilians, rather than the government where they might be collectively damaged. Seen from the perspective of the documented history, we have never seen a large-scale destruction of ancient paintings in the Ming and Qing Dynasties, if there were only several authentic pieces by the four masters of the Yuan Dynasty, as Joan Stanley-Baker had identified, where were the other authentic works at present?

For this problem, Joan Stanley-Baker thought these authentic pieces might be damaged, or lost, or buried, and we could not find them. For Hu Weiyong’s case, Wang Men was imprisoned, and implicated along with up to 30,000 people, so such events in history might have led to the loss of authentic pieces. Joan Stanley-Baker cited the literature to support her own view, for example, it is recorded that it was very difficult to find two authentic works in ten pieces under the name of Wen Zhengming in the market in a few years after Wen Zhengming’s death.

In Shao Yan’s opinion, Joan Stanley-Baker’s identification separated the imperfect works from the perfect ones and considered them as other people’s works, with preference for the masters. As far as Wang Meng was concerned, the level of his works had ups and downs, and it was possible to adopt different styles of creation during the creative period of more than 20 years. But Joan Stanley-Baker believed that when a masterpiece was created, a few years later there would be fake pieces on the market, as time went by, the authentic pieces and the early fake pieces disappeared, while the new fake pieces were increasing every year, and in the future one might consider the fake pieces, which had a similar pseudo-style, as the “authentic pieces”. Since then, the authentic pieces disappeared in history.

Shao Yan admitted that making fake paintings has been rampant throughout history. An anonymous book of the Song Dynasty entitled “Treasures Collection” could be regarded as the “Sunflower Collection” of the antique world, recording what things sold well, how to identify them, the characteristics of Chinese calligraphy and paintings, as well as bronze ware, indicating the pseudo-market was flourishing. Many surviving paintings of the Song Dynasty might be fake works at that time, and it became anonymous work if the name was lost. Shao Yan said that the pseudo-activity was quite active during this time, Mi Fu once pointed out that a collector’s collections of his works were all fake pieces at that time. When Shen Zhou created a new pattern in the morning, there were many fake pieces in the market at noon, and counterfeiters even found that Shen Zhou inscribed and added seals to the counterfeits. Wen Zhengming also had many ghostwriters. However, it was an interesting phenomenon. The excellent counterfeiters, such as Qiu Ying, Wang Hui and Ren Bonian, established their own school and had an unique style at last. Therefore, Shao Yan believed that many authentic pieces of Wang Meng, Wang Ximeng and other masters survived. She also pointed out the changes of horizon and spatial structure determined the identification, as proposed by Joan Stanley-Baker which were mainly from the concept of Westerners, which was not the main view for her own dating. The dating for Shao Yan is based on and considers the quality of ink & brush, as well as the power of lines.

In this dialogue, two art historians gave their own explanations of the authenticity of the works in Wang Meng’s name. Based on the two criteria of identification and different methodologies, the two scholars’ thoughts collided and created sparks. Finally, Joan Stanley-Baker made a summary of the lecture, and said that art history was not a master’s history, a master was only an innovator of the style at that time, and scholars could not study art history from the perspective of collectors, both masters and workers’ works were part of the style of the times.

Text by Yang Zhonghui, translated by Chen Peihua and edited by Sue/CAFA ART INFO

Photo and video by Yang Yanyuan and Hu Sichen/CAFA ART INFO