What is gene editing? What does the Lulu and Nana controversy signify in human history? How to balance technology development with ethics and morals? How do these doubts and hopes find their way into art creations and expressions? As part of the 3rd EAST Season lecture series hosted by CAFA, “Editable Future —The Technological, Ethical, Legal and Artistic Perspectives of Gene Editing” was held at 6:30 pm on 12 November in the lecture hall of CAFA Art Museum. This lecture invited six scholars from different fields of study related to gene editing, who discussed the above questions from their particular professional perspectives. The lecture was hosted by Wang Yuyang, Deputy Dean of Experimental Art Department of CAFA.

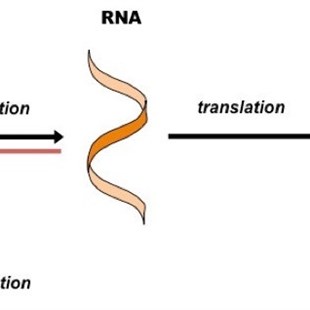

What Is Gene Editing?

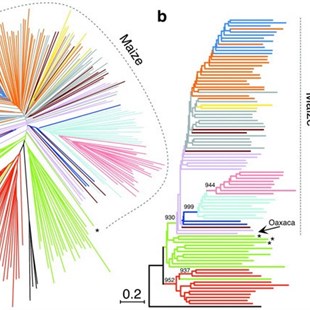

All the hereditary information of mankind is restored on 46 strands of DNA. However, the difference between the DNA of any two people ranges from only 1‰ to 5‰, whilst the difference between humans and gorillas is only about 1%. Such tiny differences in the microworld cause tremendous distinctions to our eyes, and therefore we can see the amount of information embedded in DNA codes.

However, ownership of both theoretical and technological possibilities doesn’t mean that we can edit human genes freely. Despite many benefits brought by gene-editing technology, such as increasing the output of animal husbandry, studying gene functions more precisely, etc., gene editing can turn many terrible nightmares into reality, for example, transforming a virus into super virus that targets and harms a specific group of people or designing special human beings that satisfy the demands of people in power. Certainly, ambivalent cases are worth even more consideration, such as designing “better” babies for their parents through gene editing.

Introduction and Thoughts about the Lulu and Nana Controversy

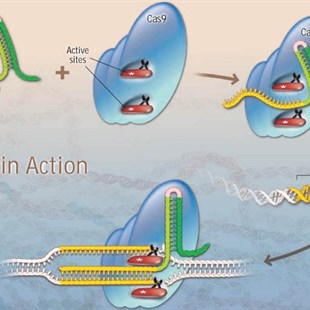

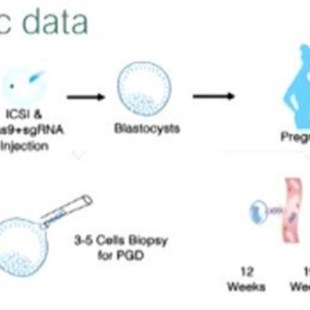

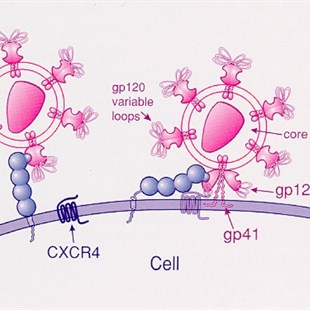

Wang Haoyi approached the topic through the case of Lulu and Nana controversy and opened up the discussion around life-editing. We need to distinguish two pairs of concepts when it comes to human gene editing: editing genetic and non-genetic cells; editing with the purpose of “curing” and “enhancing”. In compliance with the supervisory and regulatory systems of each country, we need to actively promote non-genetic editing to assist with a cure. Once we edit the gene of generic cells, the gene sequence will accompany the reproductive process of the edited body and be transmitted. As a result, “generic or non-generic” is the bottom line of gene editing. The Lulu and Nana controversy in 2018 is the first time when humans have crossed this bottom line. Gene functions are not only to be considered in its sequence, but also in its genome sequence and its environment. Breaking down the CCR5 gene might bring about consequences that experimenters haven’t expected.

The Lulu and Nana controversy by Jiankui is the first action in history of human altering their own genetic genome. But this action is rather defective from moral preparation to scientific design. So far, humans own the power to change the species fundamentally, but at the same time, we must shoulder the following responsibilities.

Moral and Legal Debates about Reproductive Human Gene Editing

Peng Yao discussed reproductive human gene editing from moral and legal perspectives. In the past 4 billion years, life has been determined by natural laws, but technological progress enables us to realize certain things from transforming to designing lives. Nevertheless, gene-editing technology has brought tremendous moral debates and challenges.

Theoretically speaking, gene editing can “enhance” some abilities of human beings in the future. In 1998, scientist James Dewey Watson proposed that “if we can make people better through adding genes, why not?”. But the key question is: what is “better”? According to Kant, dignity is treating people as a purpose rather than tools. Is editing genes of human embryos an action of treating people as tools? Besides, the clinical application of reproductive human gene editing is influenced by regions, race, coverage of public health, technological development, social and economic status, etc., which is not accessible to the masses. As a result, gene editing is probably going to widen the gap between the rich and the poor.

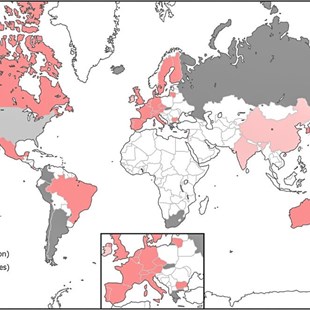

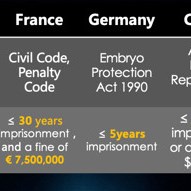

Currently, 29 countries around the globe specifically ban the clinical application of gene editing, four of which have bans without any legally binding force. Russia, Argentina, and nine countries in total don’t have a clear supervisory system for the research and application of human gene editing. Later, Peng Yao analyzed bills regarding gene editing of the U.S.A., Germany, France, U.K., Israel, and proposed that we need to improve international cooperation based on the respect of the culture and conditions of different countries, to actively shoulder the responsibilities and duties of international technology governance and to face possible challenges brought by technologies.

Governance of Gene Editing Technology: History and the Current Situation

Gao Lu tried to find strategies for governing current biotechnologies from history. In the 1970s, Nobel Chemistry Prize winner Paul Berg combined DNA sequences of different species for the first time. In 1974, in response to Paul Berg’s experiment, eight biologists wrote a public letter to the Nature magazine and proposed that the application of recombinant DNA technology should be suspended before fully evaluating the risks. In February 1975, 150 scientists, 4 lawyers, 16 media representatives and government officials from around the globe attended the conference in Asilomar and discussed the future of recombinant DNA, and the following precautionary model has become a successful example of self-regulation in the scientific field. In 1983, the National Research Council published “Risk Management in the State Government” bill, marking the establishment of the first risk management paradigm.

In April 2015, a professor at Sun Yat-sen University published an article showing his gene-editing results for the purpose of treating thalassemia. In December, a group of scientists launched a discussion regarding this article about the scientific ethics of human gene editing in Washington. However, the management system proposed during the meeting largely depends on the policy environment of each country, while the policies of many countries are not yet complete. Only three years after the meeting, He Jiankui’s Lulu and Nana controversy occurred.

Once the development of science and technology is realized, it will be difficult to control. This famous “Collinridge Dilemma” also appears in the field of human gene editing. So how should we face this dilemma? In recent years, Europe and the United States have tried to create new risk governance paradigms, such as responsible research and innovation, constructive technology assessment, and a value based design. Regarding this question, Gao Lu believed that the new governance goal should be guiding or reorienting science according to social needs.

Gene as an Art Medium

The upper-level concept of “gene as an art medium” was brought up by artist Eduardo Kac. Based on that, Jo Wei proposed the concept of “pan-biological art”, and interpreted it from five perspectives as technologies, materials, images, data, and concepts.

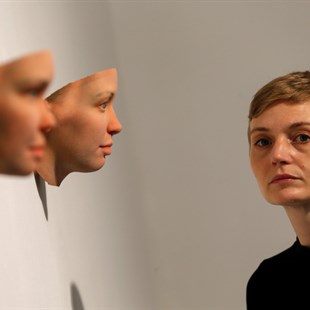

Jo Wei then took artworks as examples to illustrate different ways how genes at different levels act as art media. Ben Fry’s work “Chromosome 21” uses digital genes, where he classifies the 48 million bases on human chromosome 21 according to the effectiveness, and designs for it to be a giant, calm and solemn abstract painting, showing human self-perception on a minimalist plane. Heather Dewey-Hagborg’s work “Stranger’s Impression” starts from the material level of genes, collecting biological traces accidentally left by strangers in different places in New York, and recovering the faces of these strangers through technology. Jo Wei pointed out that in addition to poetry, this work also reveals a reality: if other people’s information is readily available, how should we legislate genetic privacy in the future?

The biological artists represented by Eduardo Kac were active in the European and American artworld around 2000. Their creations focused on hot biotechnologies at that time such as genetic modification, cloning, and stem cells, which caused huge controversies and reflections. Jo Wei believes that iterations of biotechnology have brought opportunities and dilemmas to all mankind, and artists should be keen to capture and respond to what is happening now.

Identity Issues: Where Do We Go from Here

Art is involved in the development of science and technology, and more and more artists understand biology as a means of artistic creation and reflect on human development from a metaphysical perspective.

Marta de Menezes shared her creative methodology as an artist in the field of genetic manipulation. She divides the birth of an artwork into three major steps: understanding, creation, and communication. Understanding starts with compassion, which gradually expands the perspective of the creator. After gaining a broad understanding of others’ minds, artists need to “define” their work, while narrowing their calibre of creation. When the two steps above are completed, Marta will have some diverse and divergent solid ideas. During her final implementation, the divergent ideas form a prototype, and after testing, it finally becomes the work.

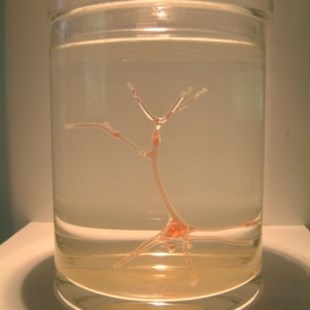

Marta’s creative themes span all aspects of the biological realm, such as “Nature?” using evolutionary biology, “Knowledge Tree” using tissue cultivation, “Protein Portrait” using proteomics, and so on. Diverse biotechnologies have become an important approach for Marta’s art creation, but Marta emphasizes that her purpose is not to apply technology. And she sometimes simply cultivates plants or explores the cultural identities of a certain plant without any technical manipulation.

Lastly, Marta re-stated the fundamental topic of this forum: what attitude should we have in considering the gene manipulation technology? Where will this attitude take us?

Text by Xu Zijun, translated by He Yuting and edited by Sue/CAFA ART INFO

On-site Photo by Sun Fangzheng, Courtesy of Lecturers