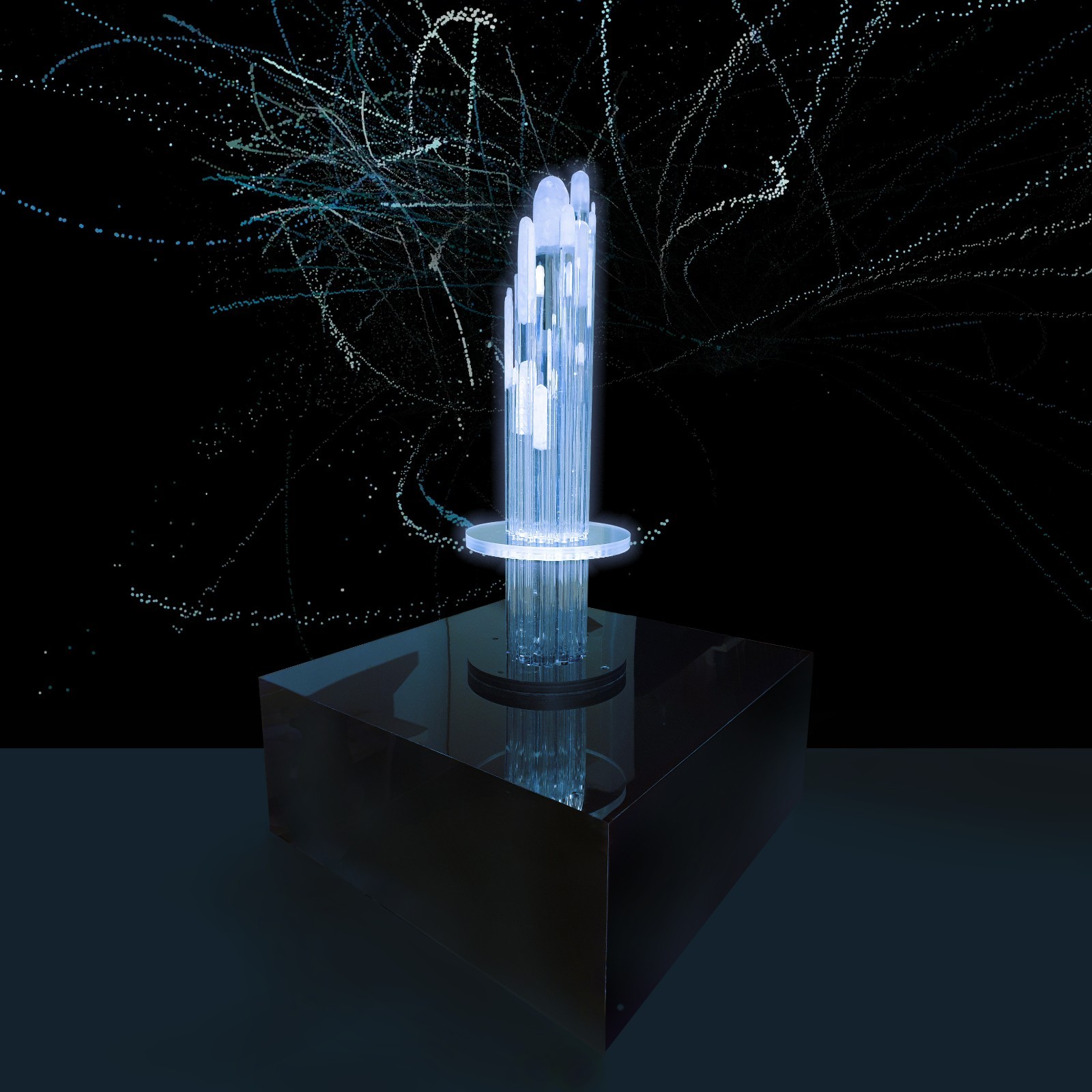

Giuseppe Lo Schiavo, Nike, still, 2022

Giuseppe Lo Schiavo, Nike, still, 2022

Since the end of 2020, crypto-technologies represented by non-fungible tokens (NFTs) have been spreading throughout the art world. As the transaction records of crypto art keep refreshing, IT terms such as blockchain and metaverse began to appear frequently in the art press. Today, AI has become a new hot topic, while the blockchain craze seems to be a thing of the past. Since the beginning of last year, the prices of various cryptocurrencies have plummeted several times. In November, FTX, the world’s second largest cryptocurrency exchange, announced its bankruptcy and huge sums of money evaporated. Last week, Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) in the United States declared bankruptcy, triggering volatility once again. The crisis in the crypto financial system has amplified the already existing scepticism, and crypto art seems to be facing a crisis of legitimacy as well.

Perhaps this is why, in the introduction to the exhibition Crypto Art: A New Possibility, which opened on 14 March, the Central Academy of Fine Arts (CAFA) Museum emphasised its academic identity: minus the power of money and the clout of speculators, we have more opportunities to think calmly and deeply about the relationships between crypto-technologies and art, between artists and art museums.

Crypto art or crypto as art?

The first issue facing crypto art is positioning, or identity, which is a tough one when one considers how identity politics plague the art world today. By name, “crypto” refers to the blockchain technology applied, thus the distinction from other art genres. Meanwhile, the connection between “crypto” and “art” is not natural and intuitive. Rather, there is a dissonance to be reconciled, with the blockchain as a system of encrypted digital records, and these (whether fungible or not) digital records are primarily used as currency. Hence, in comparison with the more traditional terms including digital art, multimedia art, etc., when “crypto” is used to modify “art”, it does not refer to an art form so much as a form of transaction. Naturally, after crypto art enters the public and professional fields, the conversation always revolves around the market. The problem is that many discussions start by making the mistake of making a long list of the characteristics of the exchange when the artworks being exchanged should be described in the first place.

HACKATAO, Pink Bear, video, 4'', 2020

HACKATAO, Pink Bear, video, 4'', 2020

Alessandro Zannier, ENT4, light installation, 60×60×90cm, 2022

Alessandro Zannier, ENT4, light installation, 60×60×90cm, 2022

In this way, the claim that “everything can be an NFT” ceases to be an ideal but becomes a problem. Crypto-technologies guarantee the artwork of uniqueness and scarcity that comes from the blockchain, but they do not distinguish it from other commodities in the blockchain. It was once believed that encryption provided assurance of the artwork’s ownership. In fact, rather than the ownership, what algorithm protects is the notion of such ownership. The protection of the actual artwork is thus stripped away, leaving only publicity and hype.

Billelis, Medusa, a victim, misunderstood, video, 15'', 2022

Billelis, Medusa, a victim, misunderstood, video, 15'', 2022

SMACK, Self Seeker, 4K single-channel digital animation, 1'23'', 2019

Then, is crypto art a contemporary “tulip mania” (note: the soaring and plummeting price of tulips in the Netherlands in the 17th century, which later became synonymous with the “financial bubble”)? This is precisely the question that an academic art museum is trying to present in this exhibition. Perhaps what crypto art desperately needs today is a figure resembling Clement Greenberg who, in a gesture of struggle, emphasised, even prescribed, the qualities of modern painting. Although no one today would consider flatness to be the essence of painting, for 20th century abstraction art and artists who have engaged in it, Greenberg provided a powerful argument for the legitimacy of identity. Similarly, Walter Benjamin’s description of the age of mechanical reproduction opened up a new aesthetic space for printmaking, photography, film and other arts. Today, the artworks of the digital reproduction age are still waiting for a truly energising discourse. In an opening event of the exhibition, it was mentioned that the CAFA students and faculty represented by the newly reorganised School of Experimental Art and Sci-Tech Art are already actively exploring this. Can “crypto” be a new medium? After taking our eyes off the market, the answer to this question is not necessarily that pessimistic.

The under-discussed decentralisation

Decentralisation is one of the most celebrated public values of the blockchain, and a hallmark of the whole utopian vision of meta-universe. Algorithmically connected, independent servers guarantee that data cannot be tampered with and can be examined in each specific unit. Decentralisation was also a quality that was repeatedly emphasised and lauded by the guests at the opening of the exhibition. It symbolises a new way of thinking that rebuilds trust and consensus, and ameliorates the symptoms of a divided and fragmented society. From a political and ethical perspective, decentralisation responds to the current overall trend of caring for the individual, the marginal, and reflecting on traditional centrism, a trend that has previously emerged mainly in the cultural sphere as “postmodern”. For this trend, crypto technologies bring forth new possibilities regarding the economy and beyond, as the title of the exhibition suggests.

Andrea Bonaceto, AB Infinite1, video, 6', 2022

Andrea Bonaceto, AB Infinite1, video, 6', 2022

It is worth noting that within this consensus on decentralisation, the same divisive tendencies that entangle crypto art itself are present. Decentralisation is thought to change the relationship between the artist and the audience, and indeed the most intuitive progress we have seen since crypto art became popular is that a large number of digital artists have found a viable way of earning an income. They tend to be inheritors of the typical Internet ethos, happy to share their creations online and often for free in order to ensure openness in the presentation of their work. In contrast, they have to earn a living in other ways, which partly influences the professionalism with which their status as artists is perceived. The fact that most of the artists in the exhibition have experience of working in the pop culture industry, such as fashion, film and games, is testament to this.

Federico Clapis, R3d Light District, video, 27'', 2022

Federico Clapis, R3d Light District, video, 27'', 2022

DotPigeon, Class of Losers, video, 30'', 2022

DotPigeon, Class of Losers, video, 30'', 2022

However, it is questionable whether the potential economic community constituted by this new distribution can have a direct impact (or a positive one) on the emotional and political community. The belief that the untamperable information guaranteed by encryption also guarantees consensus, which has even led to the slogan “code is law”, is misplaced. It was only after seeing the unbridgeable rupture between the first and second critiques that Immanuel Kant proposed a third critique on judgement. Likewise, the decentralisation that secures transactions cannot be a direct basis for connecting aesthetics and politics. In the second half of the last century, continuing Kant’s efforts, Jürgen Habermas, confronted with the problem of modernity and pointed out that there was no intuitive correspondence between factuality and validity, but that such a connection must be based on communicative action, thus putting forward the famous concept of “public space”. In the context of blockchain, facts are “dictated” by algorithms, which ensure that the virtual world imitates the natural part, not the legal part. Decentralised transactions in themselves are not sufficient to create a decentralised public space. Communities cannot be sustained by factual judgements such as “you’d die if you don’t breathe.” We all know that no one (at least in China) doubts the factual existence of the new coronavirus, but the conflicts over it are real and complex.

Installation Views

Installation Views

And so, we return to the identity confusion of crypto art, and its dependence on the market. Rather than guaranteeing “belief”, crypto is more about “credit”. Perhaps this is why one cannot help but repeat the reference to the price of crypto art. Ultimately, this issue also manifests itself in the concrete presentation of the exhibition. While the works on display share a critical and open attitude towards major issues such as capital, gender, race and the environment, the exhibition itself fails to establish a convincing enough connection between these themes and their presentation, or highlight the uniqueness of crypto art from a perspective of medium. For the audience who is more interested in visuals, it may be very difficult to distinguish crypto art from multimedia art (which, given the form of most of the works, could just as easily be called video art).

Beeple, hey, still, 2021

Beeple, hey, still, 2021

SUI Jianguo, Nibiru: Solar System/Earth, MP4 video, 8'8''

SUI Jianguo, Nibiru: Solar System/Earth, MP4 video, 8'8''

Such difficulty illustrates that regarding decentralisation, art museums also face the new challenge of identity. The exhibition proves that, at least in the traditional dislaying form of an exhibition, the community envisioned by decentralisation is unrealistic. Although traditional art institutions can use the blockchain to manage users, the radical dimension of decentralisation includes the deconstruction of various agency mechanisms. Today, we can accept art museums displaying replicas for research purposes, but if for certain art, art museums can only display replicas while the original works can be directly purchased and viewed through our mobile phones (the ones in our hands may even display clearer than on the screen in the museum), will we still go to the museum? Since decentralisation is a prominent value of crypto art, art museums cannot just treat it as a digital collection. To envision their image in a truly decentralized artistic utopia, art museums must expand their imagination greatly.

Beyond AI, will we have our own singularity?

In the exhibition, crypto art is also discussed in juxtaposition with such trendy topics as AI, forming the whole landscape of technology-inspired art projects. For most non-technology professionals, the more common concern is whether digital technology is really about to reach the singularity (note: singularity, or technological singularity, refers to a point in time when technological development, as it continues to accelerate, eventually reaches a level beyond human perception). Another typical expression is: “Will we soon be replaced by AI?” This is by no means whimsical; after all, the word “soon” was not often included in this question only a few years ago. At the same time, the technophiles (a growing group) often claim that technological progress is absolute, and unstoppable as a historical process, and the opponents are Luddites, which refers to the craftsmen who smashed the machines in the Industrial Revolution. The problem with this argument is that it is a degenerate way of understanding the “post-human” situation nowadays.

CB Hoyo, Hoyoby's, video, 26'', 2022

CB Hoyo, Hoyoby's, video, 26'', 2022

The AI threat theory is further amplified by the fact that AI today can already produce paintings while art is considered to be a critical territory that marks the creativity of human civilisation. But when we revisit it, we see that this anxiety is off the mark. The question of whether AI can do what artists do cannot be discussed in terms of technology, and we have long since stopped considering technology as a determinant of artistic value. The real question is: while AI can help us accomplish complex work quickly, are we ready to do the “really important work” that has been indefinitely postponed because of the “heavy workload at hand”? As a matter of fact, this is not a new idea, as Karl Marx had already envisaged the future in this way.

Annibale Siconolfi, Flow, video, 2'10'', 2022

Annibale Siconolfi, Flow, video, 2'10'', 2022

Marx also took part in our discussions in various ways. On AI replacing humans, how much attention is really paid to the fact that maintaining AI actually relies on multiple levels of human labour? What does it mean that a painting produced by AI may win first place in an art competition? The point is not whether an award should be given to the AI, but whether it should be given to the person who submitted this work. The behaviour of this AI user reflects an issue that is often overlooked: when using AI, we are actually consuming, consuming the labour of the AI developer and the vast amount of human labour that AI utilises technology to collect. The paradox is that AI technology benefits from an idealised human community, but its own attribute of commodity is situated within the logic of capitalism. AI applications may strengthen the “happy bachelor” imagination cultivated by neoliberalism: through the capital market, individuals no longer need to establish complex social connections with others, and can earn income through their professional competences. As long as they have enough income, they can take care of themselves through consumption and live a decent life. This fantasy misses at least two points. One is that the market does not remove others from our lives, but merely renders them invisible. The other is that some important work never generates sufficient income (e.g. digital artists who actively share their creations while being used by AI as a source of data).

Giuseppe Lo Schiavo, Nike, still, 2022

Giuseppe Lo Schiavo, Nike, still, 2022

Bruno Latour reminds us, with the notion of the mimetic object, that the subject and the object are never opposing categories, and that the perception of the object always defines the subject. The refusal to see this brings with it all the anxieties of the subject. In the face of technology that may offer a new definition of human emancipation, we are constantly using it to alienate the human being from the position it once occupied, thus interpreting “post-human” as a horrific landscape in which “humans are consumed like objects (commodities)”. Despite the fact that AI technology creates new energy in people, the anxiety of people being replaced by AI suggests that we are still failing to acknowledge the countless human labour and creations that have shaped the world.

Luna Ikuta, Remember Me, video, 1'30'', 2022

Luna Ikuta, Remember Me, video, 1'30'', 2022

GREEN Project-KIRUNALABS, MANGROVES UTOPIA, video, 5'', 2022

GREEN Project-KIRUNALABS, MANGROVES UTOPIA, video, 5'', 2022

In capitalism, labour is unseen often because it is unquantifiable. It is here that we discover the potential of crypto art, which continues a human tradition with a long history: people spontaneously coming together to share knowledge and act together out of various beliefs. What blockchain provides for this is a means of quantification. The boom in the past two years reminds us that to truly realise the potential of crypto art, quantification cannot be reduced to a price tag. Along Latour’s line of thinking, the essential question is whether, beyond technology, humanity itself can usher in the singularity? To abandon all illusions of narcissism and fetishism, to reconfigure the relationship between human beings and things (nature) with determination, and to act positively towards this end, which can be summarised as “all things are connected, as we are to each other”, that is the ethical value of “post-humanity”. In the network of such actors, both blockchain and AI have the opportunity to be our powerful companions.

A Dialogue after the Opening Ceremony for the ExhibitionFrom the left: WANG Chunchen, Deputy Director of CAFA Art Museum; Pier Giulio Lanza, Founder and Director of Dynamicart Museum (Milan); Maya Zhang, Curator of Dynamicart Museum; and Richard Wearn, Professor of Art at California State University, Los Angeles and Artist Text (CN) by Luo Yifei, edited by Emily Weimeng Zhou (CN), Sue Wang (EN)

A Dialogue after the Opening Ceremony for the ExhibitionFrom the left: WANG Chunchen, Deputy Director of CAFA Art Museum; Pier Giulio Lanza, Founder and Director of Dynamicart Museum (Milan); Maya Zhang, Curator of Dynamicart Museum; and Richard Wearn, Professor of Art at California State University, Los Angeles and Artist Text (CN) by Luo Yifei, edited by Emily Weimeng Zhou (CN), Sue Wang (EN)

Image Courtesy of CAFA Art Museum

About the Exhibition

Crypto Art: A New Possibility

Dates: March 14-24

Venue: CAFA Art Museum