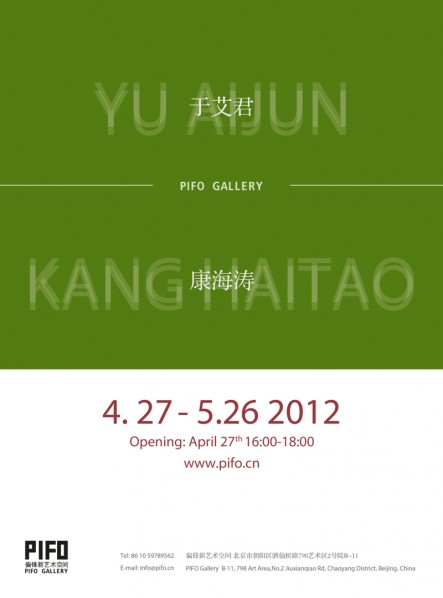

As spring awakens in April, PIFO New Art Gallery is happy to present a dual exhibition: 70's generation artist Kang Haitao's "A Burning Within" and a young oil painting professor from Luxun Academy of the Arts Yu Aijun’s “Ink.” This exhibition will continue until May 26.

After 30 years of contemporary art in China, the current era has been called materialistic, hollow, post-modernist, etc. No matter what you call this era, our spirits depend on being moved, and painting gives us that opportunity. Kang Haitao’s work is very important in this regard, as he has gone beyond the confines of the conceptual symbols of contemporary art, and returned to pure and simple painting.

Unlike art that relies on “pictures” to speak, Kang Haitao speaks through the language of painting, using the “act” of painting to express himself. This “act” is a process that he experiences, and this process emerges perceptibly in his works. The works take us in two seemingly opposite directions, but clearly show us the process of the “act” of painting that he experiences, thus differentiating him from other artists of his generation. This “act”, in the release achieved through the works’ details, gives Kang Haitao a special place amongst his contemporaries—he displays painting at its pinnacle, imbues the language of painting with his own experience, and even demands a metaphysical understanding. In the tide of today’s popularized images, this is especially rare, and deserves our continued attention and interest.

Kang Haitao was born in Chongqing in 1976, graduated from the oil painting department of Sichuan Academy of Fine Arts in 2000, and lives in Chengdu.

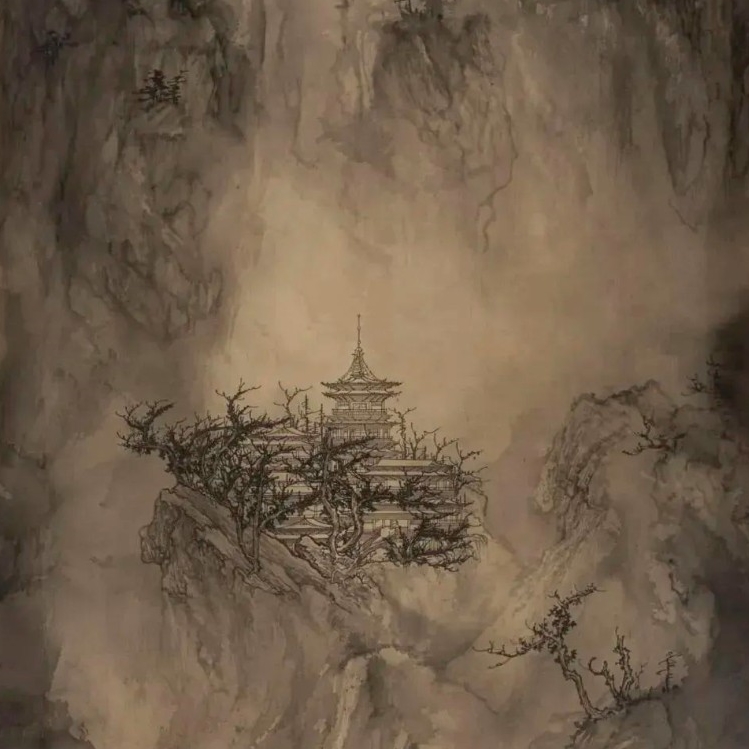

In a time of undifferentiated and deficient imagination, Yu Aijun’s works give us a new understanding of originality. How do artists both follow the pulse of the age and maintain a discernible individual quality? In today’s excessive production and conspicuous ambition, Yu Aijun’s art is a bold “return” that gives us hope. Yu Aijun resides in a remote city, is content with being on the fringe of society. This is his conscious choice for his life, and a prerequisite for his unique reflection. The almost 1000 ink paintings created in the past three years illustrate a strength of expression, and reflect an unusually exceptional value system and confidence; they share something with reading and realization, and are grounded in the artist’s innate character and cultivation of gifts.

Yu Aijun was born in 1971 in Liaoning province, graduated with a master’s degree in 2004 from Luxun Academy of the Arts’ Oil Painting Department, and currently lives in Shenyang.

[gallery link="file" orderby="title"]

About the Exhibition

Artists: Kang Haitao,Yu Aijun

Duration: April 27th—May 26th

Opening: April 27th 16:00~18:00(Friday)

Address: PIFO Gallery

B-11, 798 Art Area, No.2 Jiuxianqiao Rd, Chaoyang District, Beijing, China

Tel: 86 10 59789562

E-mail: info@pifo.cn

Web: www.pifo.cn

The Release of “Painting”--Kang Haitao’s Visual Composition

by Hang Chun Xiao

When Kang Haitao painted a group of abstract works, people familiar with his “night scenes” were astonished: how could he go from his “representational” works to this? It became an oft-asked question, but is not all that strange. Because most people’s comprehension of painting enters directly through the images, they are used to the imagination given by “forms”. As soon as the forms on the canvas transform, comprehension suffers from inertia and lags behind, which is what happened with Kang Haitao’s two series. Kang Haitao has realized this situation and put forth a clear answer: these seemingly abstract works are really what is left over from his “night scenes”; it’s a casual painting, expressing an individual understanding of painting at rest.

Is this really what happened? Are these abstract pieces really not at all connected with his “night scenes”, just the product of an idle hand? The answer is that it’s not necessarily that simple. Of course, some people will doubt this conclusion—the artist himself put forward this explanation, so why should we complicate the issue? There’s no question, the doubt is fair. But the artist’s explanation is not the whole story. For one thing, the artist’s intuitive way of thinking makes it difficult sometimes to express things clearly. For another, in the process of completing a canvas, he often doesn’t use visible logic, but proceeds into the hidden subconscious mind. Therefore, face to face with his works, it’s true that the artist’s own explanation is important, but it’s not a standard answer. This interpretation is not in order to negate, but to explain—let us break away from a fixed “description”, and look again carefully at the paintings to uncover a different kind of visual experience. Actually, the answer is not important. What is important is whether we can discover an even richer experience. This is, perhaps, the highest value of art.

So, facing Kang Haitao’s two seemingly unconnected series, how should we launch a completely new expedition of vision? The starting point, of course, is the canvases. First, let us turn our attention to these abstract works. In terms of the visual result, they are in line with our customary concept of abstract art. But looking more closely, we discover: they are not simply formalistic abstraction because the pieces don’t have a specific abstract goal, but a kind of process of “revision” through constant overlaying. These particular works have kept traces of the “original sketch”, but this blueprint often has no relation to the finished work. In other words, when Kang Haitao was creating these works, the ongoing painting process altered the original plan over and over again. Of course, the revising effect of “the process of painting” on the “original plan” is not new, but generally, we don’t pay attention to those “process” traces—they are forgotten as inconsistencies, or it might be that they are blocked, thus guaranteeing that all we reflect on is the finished product. However, Kang Haitao is clearly different. He intentionally destroys our expectations, and maintains all the marks of revision—even if they have nothing to do with the finished work. Thus, in the constant adjusting and changing of his painting process, Kang Haitao gives us a “transparent” visual composition; in revising again and again, the value of the act of painting emerges, not just painting as a means to an end.

In terms of “painting” as a personal experience, not just a tool of expression, perhaps Kang Haitao is trying to convey some essential information. The so-called abstract pieces indicate that the artist is infatuated with “painting” for himself. They don’t necessarily have a specific visual goal, only to release him from the use of painting as a tool. And through this “release”, we can delight in painting’s original experience in a new way. These abstract works are, in Kang Haitao’s infatuation with the experience of painting itself, an attempt to show us a transparent vision.

So, how is this kind of attempt at transparency connected his “night scenes”? To answer this question, we have to return to the differences between Kang Haitao’s particular “night scenes” and normal night visions. In regards to the visual result, his “night scenes” transform normal visual experiences into unfamiliar visual paradigms, and in this uncertainty, create a kind of calm and distant mental projection. But how does he get from the things we see at night to these projected “night scenes”? Returning to the canvas, we can see that Kang Haitao’s “night scenes” are different from night scenes in reality because he gives us night with disorganized layers of shadow and light. This is an extremely distinctive way of viewing things. Logically, the appearance of images at night depends on some kind of focused light source, and the concentrated area of contrasting shades. But this logic is not what we see with our own eyes. To our eyes, light is not necessarily that focused, but soft and diffused. Kang Haitao grasps and emphasizes this point, giving us a different kind of “night scenes”. So, the question is, how does the artist utilize this angle of observation?

Once this question is put forth, the relationship between Kang Haitao’s two series of works begins to become clarified. The reason is simple: the pervasive layers of light in the “night scenes” depend precisely on the multiple-level revision and layering style in the abstract works. Actually, the unique visual characteristics of the colors of night under Kang Haitao’s brush originate in his unique language of acrylic application. Looking at the surface, this kind of language serves painted forms, like landscapes of trees and walls. But this process of layering the details is not necessarily “re-creation”, but the rhythm of painting language itself. We have a hard time seeing concrete representations of objects; it’s more a process of layering accumulated colors. This feeling is exactly the same as the multiple-layer revision of painting language in his abstract works: it is process of experiencing “painting”, and this process emerges perceptibly in his works. Even though Kang Haitao’s works take us in two seemingly opposite directions, they clearly show us the process of the “act” of painting that he experiences, thus differentiating him from other artists of his generation. Looking from a certain angle, this “act”, in the release achieved through the works’ detail, gives Kang Haitao a special place amongst his contemporaries—he displays painting at its pinnacle, imbues the language of painting with his own experience, and even demands a metaphysical understanding. Unlike art that relies on “pictures” to speak, Kang Haitao speaks through the language of painting, using the release of painting to express himself. In the tide of today’s popularized images, this is especially rare, and deserves our continued attention and interest.

April 10, 2012, Wangjing

Art’s Cool of Night

by Chen Lingyun

At some point, I don’t remember when, Yu Aijun started emailing me photos of his ink paintings. He modestly called them “little works”, and then gave them all sorts of graceful names: “Hidden Spirit”, “Extinguished Fire”, “Empty Valley”, “Tangled”, “Evening”. Whenever he came to Beijing we would eat and talk, speak of these “little works”, speak of exhibitions and collecting. Now, finally, his dream is coming true. When I edited Jiang Xun’s “Six Talks on Loneliness”, I used some of Aijun’s paintings for the illustrations, which he readily agreed to. Looking at the finished book, I think the paintings fit perfectly with the articles about loneliness.

Aijun doesn’t talk much. We’ve never spoken in detail about his “little works”. I was asked to write an article for his exhibition, and as I am not very involved in art, when I tried to use “artistic” words to discuss these “little works”, it ended up feeling stiff. As I was thinking about the article, before I knew it, night had fallen. Outside the window the bright moon was high above, and in a flash I returned to the sleepless nights of my youth.

I thought about Heinrich Heine’s poem: “Our death is in the cool of night/our life is in the pool of day/the darkness glows, I’m drowning/the day has tired me with light”, and how I fell in love with its quiet waning. Thinking back, youthful nights are not necessarily all peaceful coolness; they actually bubble with secret, bright desires. In the jumble of indescribable distress, ripe shame and unrestrained self-pity, sometimes, in the moment before dawn, you can hear the far off train’s whistle, and in a second it seems you understand yourself, understand the world.

I’ve long forgotten those nights. When I see these paintings, I think to myself: In Aijun’s heart, there might reside a love of the nights of youth. He wrote in his “notes”:

“All eyes, every cell, all distracting thoughts are shut, deeply hidden, there are only corn leaves steaming, unfolding, spreading, like a green pestilence. Besides the pumping of my own blood, there is no other sound, only wind—only wind, like a sob. The corn field surrounded by black mountains, all eyes on the corn field. The black corn field hides a secret.”

For me, Aijun’s paintings have accumulated the secrets of northern country nights, and they hold a youthful desire and loneliness. I tend towards the pure imaginative scenes, pinks, deep blues, washed rings of light. Some of his works have strong overtones of symbolism, less silence. I don’t know how Aijun transmits northern desolation through this intricate screened beauty--perhaps the secrets come from the nights, from the village, from the ink and the paper.

I will say that Aijun’s paintings are “art’s cool of night”.

What is “art’s cool of night”? It is the water marks left after the tide has ebbed out; the first breath of wind on the earth after it cools; what is left between the eyebrows after worry has dissipated; the gradual exposure of everything after the fire is extinguished; the souls muttering to themselves after the falling of silence. It is the world returning to the earth, ART returning to artistry, art returning to action. In this adrift and disconnected moment, painting returns to painting.

What significance does today’s painting have? This is the question that every painter must face. The answer may be clever or earnest, but all are somewhat adrift. Aijun has tried his hand at many different forms of art; when I listen to him talk about it, I don’t entirely understand, but get a vague Don Quixote-like melancholy.

I am happy for Aijun, for in this kind of painting he has discovered a way to communicate with himself. I can’t begin to imagine his mood while painting these 1000+ works—the painters of pre-historical cave murals drew wild cow forms in endless darkness and dread.

And now these nighttime paintings will be exhibited in daylight, and here they will be gathered together. We must approach them quietly and gently, not be alarmed at these little works, allow them to remain in the starry night side-by-side with youthful desire, to smolder undisturbed.

April 8-9, 2012

Courtesy of the artists and PIFO Gallery, for further information please visit www.pifo.cn.